Figuring out which companies are likely to succeed is one of the toughest problems in business. But even very dry data from business registrations can tell you a great deal, according to a new NBER working paper from researchers at MIT. Even though the authors have come up with a robust way to predict growth, one of the biggest factors is still timing.

In a dataset from Massachusetts, 77% of growth outcomes (an IPO or acquisition within 6 years of being founded) came from companies in the top 5% of the quality measure the authors created, based on everything from how a company is named to how quickly it files for patents. Nearly 50% of successful outcomes were in the top 1%. A similar dataset from in California produced remarkably similar results for the researchers (paywall).

But their model doesn’t account for everything. The highest potential entrepreneurs in a dataset that ran from 1988 to 2014 were from the class of 2000. But entrepreneurs in 1995 had a far, far greater chance of success.

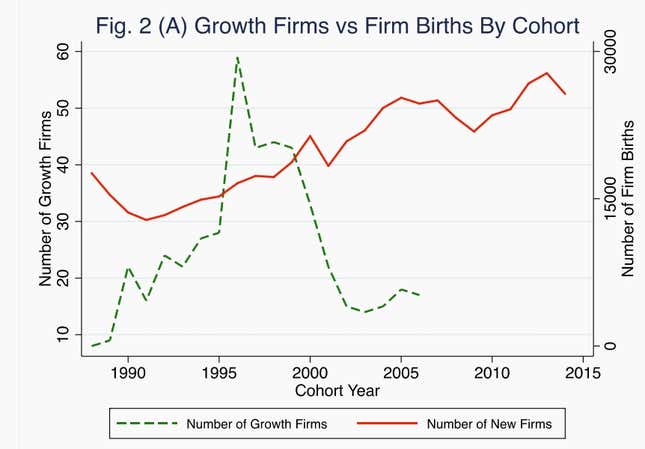

Timing matters, a lot. The earlier entrepreneurs got more time in a growth market, and were more likely to be successful. Their years of success attracted more people and made the early stages easier, but high potential means very little in a tough market. There was a huge spike in the number of firms that exited successfully around 1995—they got the full benefit of the boom, and suffered fewer of the consequences of the tech-bubble bust:

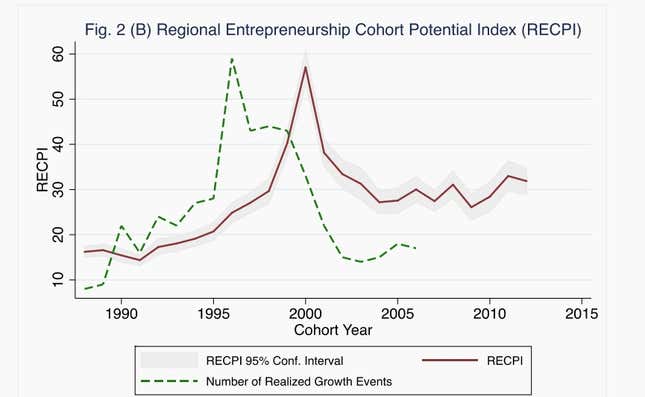

The height of entrepreneurial quality was actually at the very end of the bubble. But they had a substantially harder time making it, and that difficulty persisted for years after the bubble burst. RECPI is the average quality of firms multiplied by the number of startups created in a given year in a particular area, the state of Massachusetts in this case:

So what sort of data predicts success? It’s a few, surprisingly simple, things. Registering as a corporation rather than an LLC or partnership means a company is five times more likely to be successful. Registering in Delaware (a particularly business-friendly jurisdiction) is associated with a 40 times greater chance. Filing for a patent within a year of starting means a 60 times greater likelihood of growth.

Names matter: successful firms tend to have short ones (3 words or less). An company named after a founder has only a 5% chance of success, compared to one that isn’t. And an early mention in the Boston Globe business section was associated with a 30 times greater likelihood of success.

The difference between a firm that satisfies many of the quality metrics and one that doesn’t is pretty startling. The odds of a Delaware corporation with a patent and trademark succeeding compared to a Massachusetts LLC without intellectual property is 3097:1. The authors go even deeper:

More dramatically, at the (near) extreme, comparing the growth probability of a Delaware corporation with a patent, trademark, media mention and non-eponymous short name with an eponymous partnership or LLC with a long name but no intellectual property or media mentions, the odds-ratio is 295,115 to one!

It’s not causal—just registering in Delaware won’t make a company successful. But it’s an excellent signal of the ambition and potential of a company at a very early stage.

This data isn’t likely to give investors an advantage, but for governments trying to grow jobs and encourage entrepreneurs, it’s a way to focus on quality over quantity.