A hole $21 trillion deep

After the financial crisis—and the demands it placed on government balance sheets—a 2009 summit of the G20 economies decided to do something about the world’s gigantic tax-avoidance problem. According to Britain’s Tax Justice Network, at least $21 trillion and as much as $32 trillion of “unreported private wealth” is being held in tax havens worldwide. The summit launched more than 300 international treaties to force countries acting as tax havens to share information about cross-border bank activity.

Beyond boosting public finances, chagrined officials were attempting to prevent future disaster. In 2007 and 2008, the largest single foreign concentration of US mortgage bonds—the flawed financial instruments at the center of the US housing bubble—was in the Cayman Islands, a notorious tax haven, according to the International Monetary Fund (pdf; p. 3). Parking assets in a tax haven can simply be a way for a bank to reduce its tax bill; but because such jurisdictions typically don’t report details about transactions or ownership to other governments, they conceal financial flows and conflicts of interest from regulators, making it difficult to catch the kind of behavior that could warn of impending crisis.

To bet on the US housing market, Goldman Sachs registered a $2 billion collateralized debt obligation called Abacus 2007-AC1 in the Caymans. Three years later, Goldman paid US regulators $550 million to settle allegations, without admitting wrongdoing, that it had stocked Abacus with bonds the bank expected to fail, then bet against the very investors to whom it sold the instrument. It was one of hundreds of Goldman investment vehicles securitized off-shore.

Of course, it’s not just the last financial crisis that felt the effects of tax havens. Illicit capital flows out of Greece topped $261 billion from 2003 to 2011 according to research by Global Financial Integrity, a non-profit that tracks illicit capital flows, and the country’s rampant tax evasion has become a sore point as it works through a European bailout.

Failed first attempts

The blitz of tax treaties emerging from the G20 summit in 2009 made it the single greatest international effort to confront tax avoidance in history. “The era of bank secrecy is over,” OECD secretary-general Angel Gurría concluded piously last November.

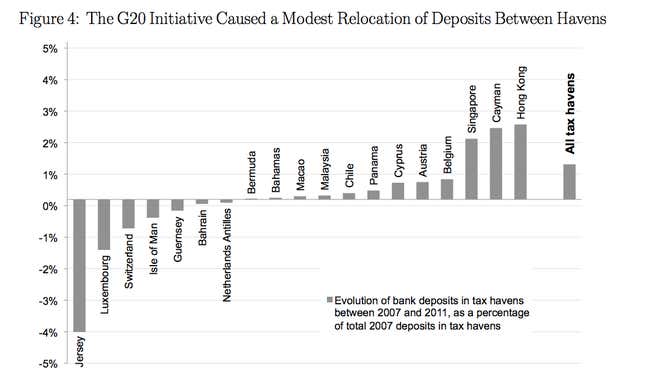

But when economists at the University of Copenhagen and the Paris School of Economics analyzed the results of the treaties (PDF) earlier this year, they found little change in the funds deposited in tax havens. Mostly, the illicit money flowed from European tax havens like Jersey, Luxembourg and Switzerland, which were more likely to sign new treaties, to tax havens that weren’t, like Singapore, Hong Kong and the Cayman Islands. Some world historic effort.

The secrecy continues, the economists said, because most tax treaties require a lot of bureaucratic hoop-jumping for governments that hope to check on their citizens’ finances. To make a request, they need key details about the account—what name it’s under, what bank it’s in. It takes the US Internal Revenue Service 50 to 100 days, on average, to clear an incoming request.

The way to deter illicit money movers, both the researchers and anti-tax cheat organizations suggest, is automatic information exchange between governments. But many states are reluctant to enter into the complex negotiations required of such a deal, especially if the talks are multilateral.

America, the world’s tax policeman…

The lack of a strong global tax framework has prompted the US to take international law into its own hands. In 2007 Bradley Birkenfeld, a whistleblower at Swiss bank UBS, got in touch with the US Department of Justice, offering to reveal how the bank helped US citizens evade taxes. Eventually, UBS would pay a $708 million settlement, the Swiss government would bend its bank secrecy laws to share the names of account holders with the US, and Birkenfeld would serve three years in prison, which ended in August of this year. He was also awarded $104 million—his due cut, as the US government’s informant, of the damages that it had won in the prosecution. (Hopefully he’ll be paying his taxes on the windfall.)

The episode spurred Congress to adopt the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), which goes into effect in 2013. Any financial institution that does business in the United States will have to report to the US Internal Revenue Service the names, addresses, account activity and tax identification numbers of American account holders, or face a 30% withholding tax on its US income. The rule is even applied to pass-through payments with third-party institutions who might never do business in the United States.

Banks were stunned. “The reaction was at first disbelief at the extra-territorial nature of the legislation, and the decision of the IRS to seek this information from financial institutions as opposed to governments the way it had been done traditionally—it took people quite a while to come to grips with the breadth of the legislation,” says Francisco Duque, a lawyer with Linklaters in New York City who is working on compliance strategies for affected clients.

The law has been little-noticed in the United States, except among Americans who hold money abroad; 33,000 of them declared foreign accounts during an amnesty period. But it has infuriated financial institutions who may have to spend millions to comply with the law’s reporting requirements. It also conflicts with some privacy and disclosure rules in these institutions’ home countries. One result, presumably unintended, is that Americans living abroad who want a local bank account now find it harder to open one.

Duque says that non-US banks’ anger at the law is mostly about this cost of bureaucracy, not the possible loss of would-be tax evaders as clients. The European Commission has estimated the cost of compliance for banks in Europe to be about $100 million, and industry estimates (though these should perhaps be taken with a grain of salt) range as high as $7.5 billion for the top 30 foreign banks. By comparison, the IRS estimates it will recover about $8 billion more in tax revenue over the next ten years because of FATCA.

…or the world’s biggest tax haven?

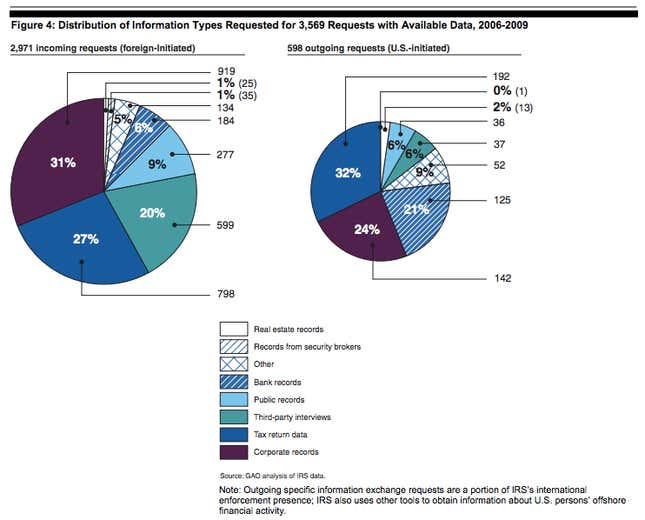

One reason for the international uproar about FATCA is that the US isn’t innocent of receiving illicit flows of capital. While it doesn’t have the bank secrecy rules other havens boast, the world’s largest economy attracts a lot of foreign investment, and it’s easy to blend in thanks to lax rules about identifying shell companies in states like Delaware, Montana and Nevada. The IRS reports more receiving more requests (pdf) for tax information from revenue collectors countries than it sends out:

That’s backed up by some independent analysis. Global Financial Integrity estimates (pdf) that the US is the world’s leader in hosting private, non-resident deposits. The World Bank’s Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative ranks the United States (pdf) as the most-abused venue for the formation of shell companies to hide foreign assets. And a forthcoming study finds that in OECD nations, including the United States, registering a corporation without identifying the real owner is even easier than it is in places traditionally considered tax havens.

One example in the World Bank’s report is Teodoro Nguema Obiang Mangue, the son of the President of Equatorial Guinea. According to a US Senate investigation (pdf), he moved at least $110 million to the United States through a shell company called “Sweet Pink Inc.” despite an official salary of some $60,000 per year. The World Bank makes illicit capital flows a priority because developing countries like Equatorial Guinea lose $20 to $40 billion a year to corruption, money that could be invested in growth.

But even though America’s heavy-handed pursuit of its own tax evaders abroad while it shelters foreign ones in America seems hypocritical, it could lay the groundwork for a real international tax infrastructure. Foreign governments and financial institutions are pushing back against the application of FATCA. New models for reciprocal, automatic information exchange are being trotted out to help ease the burden, including a UK-US agreement signed on September 14. ”One could see a path to not just bilateral solutions, but to multilateral solutions, something like a pan-EU [inter-governmental agreement] with all of the European nations and the United States, all agreeing to share the same information with each other,” Duque says.

That will be a slow process, he warns. But given the precarious public finances of rich countries and the floods of investment going into poorer ones, it’s clear that transnational tax problems aren’t going away anytime soon. The first group effort at solving them may have failed, but America’s clumsy attempts to go it alone may have the salutary effect of pushing the world’s governments into a second try.