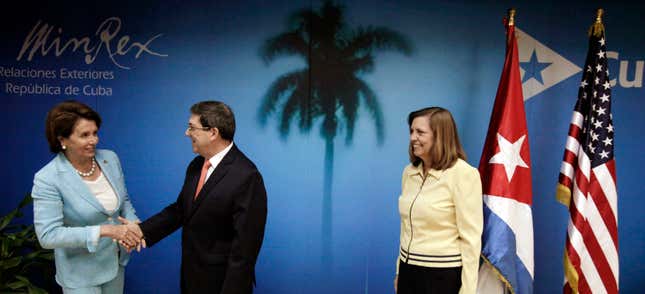

As a Cuban-American who favors improved relations between the United States and Cuba, I know I should be excited about recent political developments. Three months ago, I could never have imagined that a high-ranking congressional delegation would be visiting the island to discuss trade agreements, or that Cubans would welcome said delegates by hanging American flags from balconies. Similarly surreal were the announcements that Netflix would soon stream video service on the island (even if the clientele that can afford it is minuscule) and that Conan O’Brien would tape his popular television show in Havana. Indeed, ever since president Barack Obama’s groundbreaking announcement on December 17, it seems every day brings news of further thawing between the two historic enemies. Each week I learn of regulations lifted, negotiations initiated, commercial opportunities seized.

But while I am cautiously optimistic about the future of US-Cuba relations, my excitement is tempered by my knowledge of the past. Americans and Cubans have come close to normalizing relations before, each time reaching an impasse before any meaningful agreement could be reached.

Will the US and Cuba be able to finally craft a new relationship where both nations are equal partners? Or will they sink back into old, destructive patterns that prevent genuine relations? Do both countries have the political will to change?

Maps belie the true distance between our two countries: geographically, a mere 100 miles separate US from Cuban soil, but politics make these a very wide 100 miles indeed. The current generation, old enough only to know the bloqueo (embargo) and travel restrictions, forgets that we were not always enemies, that our economies were once closely intertwined.

On the eve of the last Cuban revolution, Americans held enormous stakes in the key industries on the island, from agriculture and mining, to transportation and public utilities. Cuba imported most of its consumer goods from the US, and the US purchased almost all of Cuba’s sugar and tobacco. Airlines scheduled hundreds of flights each week between the two countries, transporting businessmen, tourists, shoppers, honeymooners, students, baseball players, and celebrities. Cubans studied English and were avid consumers of Hollywood, Madison Avenue, and American popular culture. Americans, in turn, flocked to the “Riviera of the Caribbean” (“so near and yet so foreign”), to attend conventions and trade meetings, as well as to enjoy Cuba’s hotels and yacht clubs, its sandy white beaches, its racetracks and casinos, its nightclubs and sporting events. Business and political elites in both societies profited from this trade in economic and cultural commodities.

Meanwhile, compared to other Caribbean nations, Cuba scored fairly high in socioeconomic indexes, and many attributed this success—to quote historian Louis A. Pérez—to the “ties of singular intimacy” between Cuba and the US. Yet this prosperity masked serious inequities at home, and in diplomatic and trade relations. For most of its history, Cubans had struggled to assert economic and political independence, free from the suffocating control of Spain, and later, the US. Castro’s revolutionary struggle successfully exploited this nationalist impulse.

One day soon, it seems American businessmen will once again travel to Cuba, this time on US Air shuttles between Miami and Havana, in less time than it takes to fly between Boston and New York. Already, US agribusiness, telecommunications firms, and energy companies are intensifying their pressure on Congress to end the economic embargo so they can compete with Spain, Mexico, Canada, and the other nations that have secured economic partnerships with the Cuban government. American tourists are eagerly making plans to visit Cuba “before it changes,” as if the homogenizing effects of McDonalds, Starbucks, and Walmart are inevitable once relations are normalized.

But as Americans and Cubans look to the future, they must also study the past, for it offers a road map that both guides and cautions. If unbridled economic profit—with little regard for the human and natural resources that Cuba offers—is the sole motivator for reestablishing relations with Cuba, then Americans have learned little from this contentious history. And if Cuba can’t offer its citizens basic human rights, freedoms and opportunities, it too is doomed to repeat old mistakes.

There are still too many imponderables. It still remains to be seen if Congress will lift the economic embargo against Cuba once and for all, or if US-Cuba relations will continue to plod along on a limited basis. Will the end of the embargo bring a political shift to the island, or will communist Cuba follow the path of China (a “communism lite”)? Will capitalism bring democracy and prosperity to Cuba, or will capitalism exacerbate the inequalities? Will we see an expansion in the institutions and organizations of Cuban civil society, or will the government continue to crackdown on free expression and the brave human-rights activists on the island? Will intellectuals and religious leaders help facilitate reconciliation—and what will that reconciliation require and, ultimately, what shape will it take?

For the time being, I remain hopeful that a new era is unfolding. Yet I am keenly aware that many Cuban Americans do not share my optimism. My parents’ generation—the exiles—do not believe that a new path is possible as long as any Castros hover in the background. For them, Obama’s announcement is a betrayal, a validation of a despotic regime that forced them to abandon home, career, and nation. I understand their suspicion and resentment, but as a teacher and scholar, I do not have the option of ignoring Cuba. As a Cuban-American, positioned between political generations, cultures, and countries, I do not want to ignore Cuba. I choose to hope even though I know such optimism risks disappointment.