Faced with a stubborn refusal of wages to rise even as economies recover, some of the most powerful policy-makers in the developed world are now pushing companies to put more money in people’s paychecks. And they’re willing to risk offending the conventional economic wisdom to do it.

“Some kind of mechanism, a ‘visible hand,’ is necessary for wages to rise,” Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda told an assemblage (pdf) of influential economists, politicians and academics at last year’s Federal Reserve conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

In the world of economics, the “visible hand” is the flip side of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand,” the 18th-century Scottish philosopher’s metaphor for the free market. It’s a polite way of saying, “the government.”

And while Kuroda was talking specifically about Japan’s decades-long battle with deflation, his comments reflect an important a shift across the rich world. Politicians and policy-makers of all stripes are finally talking about using the influence of government to raise wages instead of letting markets set them. If sustained, that would be a serious swing of the pendulum away from the laissez-faire consensus that has dominated economics since the era of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

“This is now something that a lot of political leaders are backing or attempting to lead,” says Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. ”It’s a shift, but it’s not a revolution.”

Consider, for example, the following.

- In Germany, a coalition government led by the conservative Angela Merkel just put the country’s first-ever minimum-wage law into effect.

- In the US, the left-leaning Obama administration has been calling for an increase in the US minimum wage, as referendums in both Republican and Democratic states pushed minimum wages higher in recent elections.

- British prime minister David Cameron, standard-bearer of the business-friendly Tories, is openly urging companies to “give Britain a pay rise,” as an independent advisory group recommends a 3% hike to the minimum wage.

- In Japan, prime minister Shinzo Abe is leaning on exporters to to pass part of their record profits along to workers in the form of higher pay.

- And central bankers, who traditionally play the role of monetary referees in the tug-of-war between labor and capital, are now openly calling for fatter pay packets—even in inflation-phobic Germany.

Why?

It’s quite simple. Across the board there is political appetite for wage increases.

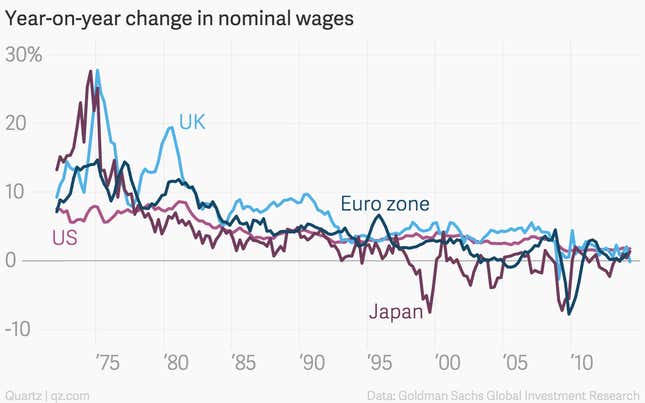

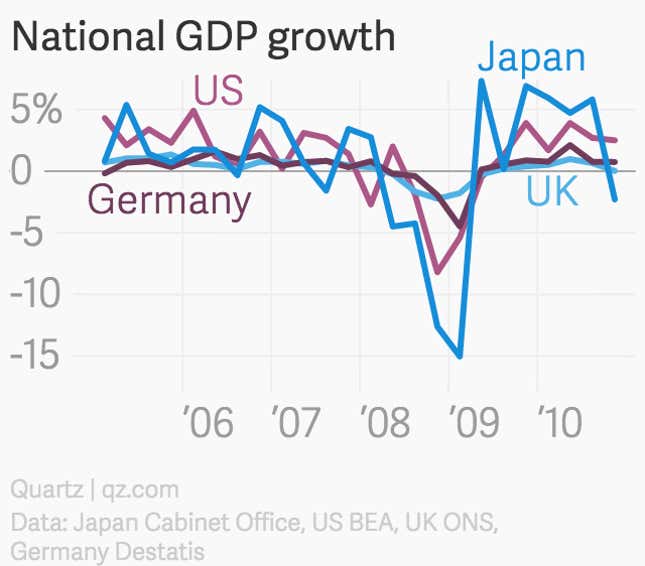

After all, the developed world has been getting some of the most piddling pay rises on record over the last few years. This would make sense if the global economy were contracting. But, by and large, it has been expanding since the middle of 2009. “The weakness of real wage growth compared with the strength of activity data—and labour market indicators, in particular—is perplexing,” wrote Goldman Sachs analysts in a note late last year.

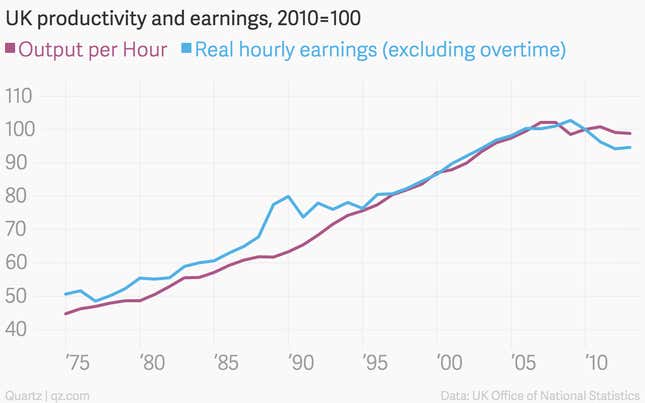

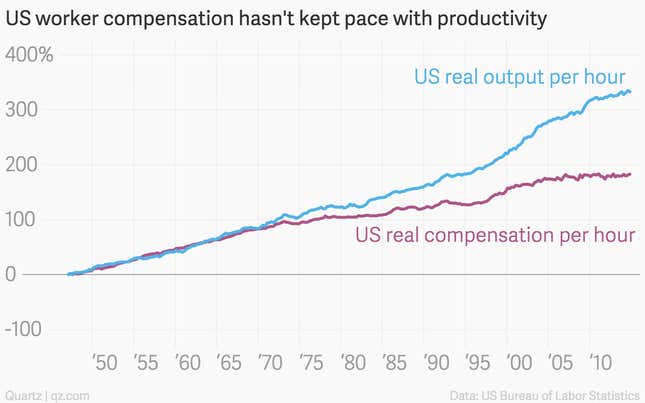

From an academic perspective, this is simply a math problem. Wages—excluding costly non-wage compensation such as social and health insurance—and job growth have simply failed to keep pace with productivity growth since the 1970s, resulting in something MIT professors Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee have dubbed “the Great Decoupling.”

According to economic theory, in a healthy, competitive labor market, wage growth should roughly track productivity. But as in most things, economic theory is a terrible guide to how wages actually move. In practice, wage growth has slowed for all sorts of reasons in these countries.

For instance, in the UK, a relatively solid run for wages slammed to a halt during the Great Recession, generating the so-called “living standards crisis” that has become a rallying cry for the opposition to the Cameron government. (An interesting wrinkle in the UK story is that productivity growth has also ground to a standstill in recent years, resulting in what’s known as the “productivity puzzle.”)

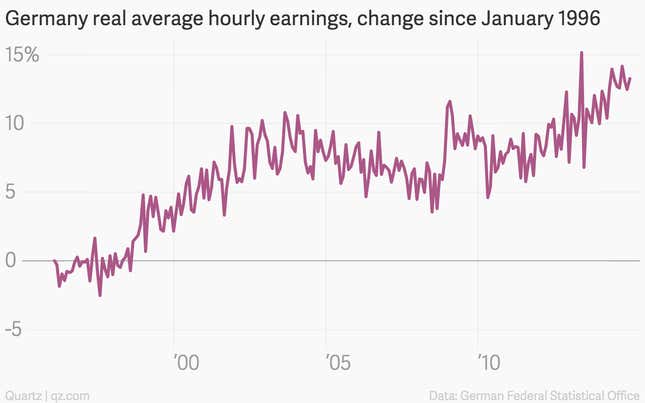

Over in Germany, flat wages were an accepted public policy goal for for more than a decade between 2003 and 2013. In 2003, a government led by left-leaning German chancellor Gerhard Schröder started pushing through a series of labor market reforms aimed at cutting the country’s labor costs, which at the time were a good deal higher than those of Britain and France. The aim was, in part, to stop wage growth. It worked. Germany regained its competitive position. So much so that it has come under pressure amid the euro crisis to let wages rise.

In the US, meanwhile, the wage stagnation story has been in place for decades. Tax policy shifts, globalization, job offshoring, declining unionization, deindustrialization, and automation have all played a role. (The surging cost of health insurance has also gobbled up cash that once would have gone to wages.)

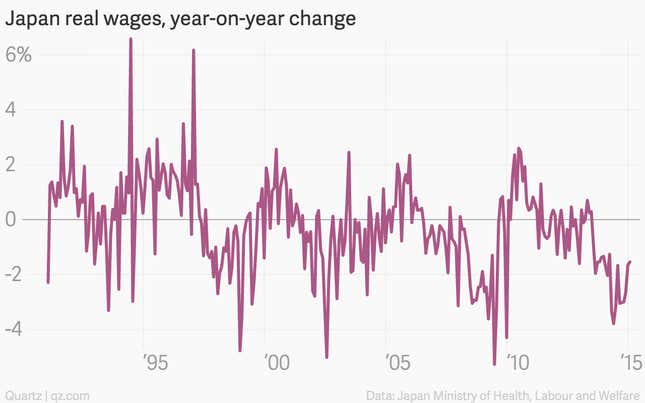

But in Japan, the story of declining wages is tightly tied to deflation. The country has been battling it since the economic miracle of the 1980s imploded in a real-estate and banking bust in the early 1990s. As prices in general have struggled to rise, so has the price of labor. While the Bank of Japan has fought deflation with an ambitious money-creation policy, Japan’s high debt constrains the government’s ability to boost spending in order to add to domestic demand. Higher wages, however, could do that job instead. “Raising wages is an alternative to raising government spending,” says Hugh Patrick, emeritus professor at Columbia University’s Center on Japanese Economy and Business.

Why are politicians trying to do something now?

Politics, of course.

As we’ve seen, weak wage growth has been a story since long before the Great Recession of 2008. But in its aftermath, governments found themselves in a pickle. Though developed economies contracted sharply during the recession, they pretty soon began expanding again. But people didn’t feel it in the form of higher wages. That has made for an exceedingly sour electorate and a fair bit of political volatility:

- In the US, then-newly installed president Barack Obama’s Democratic party took “a shellacking” in the 2010 mid-term elections, which installed an obstructionist bloc of Republicans in Congress.

- That same year, voters gave Cameron the keys to 10 Downing St., after he ran on an pro-austerity platform. Two years later, Cameron’s Conservative-led coalition was sharply rebuked in local elections.

- In Japan, Abe took over as prime minister in late 2012 after winning a landslide election, having campaigned on a revitalization of the Japanese economy (and a stiffer posture towards China).

- It’s a slightly different story in Germany, where Merkel has held on to power throughout the crisis and recovery. But in forming a grand coalition in 2013, Merkel, a conservative, made considerable concessions to her left-leaning coalition partners, the Social Democrats. Those included helping to push through Germany’s first minimum wage as well as allowing earlier retirements.

There are signs that it’s working…

In the short term, there are reasons for optimism. America’s largest private-sector employer, Walmart, last month announced an unprecedented pay increase for roughly 500,000 of its 1.4 million workers. Several other large retailers quickly followed suit (paywall). Other large employers such as Starbucks and insurance giant Aetna have also announced large-scale pay increases.

Amid broad support for higher wages, Germany’s most-powerful union, IG Metall, has won a hefty 3.4% raise for roughly 800,000 metal and electrical workers in the wealthy region of Baden-Württemberg, likely setting a precedent for future negotiations.

In the UK, Cameron’s Conservative-led government raised minimum wages in October. The technical body that makes recommendations to the government about the minimum wage has suggested it rise another 3% next October, to £6.70 an hour ($9.88). But chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne has suggested it should go even higher, up to £7 an hour in the not too distant future.

And in Japan, the government is pushing hard for labor to win wage gains in the annual shunto—or “spring battle”—negotiations between trade unions and large corporations. Toyota initially signaled it was open to higher wages. (Over the weekend, news broke that the auto giant had agreed to the biggest pay increase in recent memory.) Japan’s main auto union is doubling its demands from last year.

To be sure, strengthening economies are creating a better environment for wage increases. But observers note that there’s little sign of broad-based wage inflation. That suggests the recent pay increases stem, at least in part, from government policy shifts. ”This is not a sign that we’ve got overheating wage markets,” said Posen of the Peterson Institute. “There’s something else going on.”

…but also reasons to be cautious

Policy-makers may be pushing for higher wages, but employers—especially the powerful US corporations—may push back. After all, wage increases eat into profit margins. And while those margins are sky-high by historical standards, corporations will fight to keep them that way. What’s more, if a squeeze on their profits leads to a downturn in US stock markets, that could have political repercussions too.

Still, given that there’s little appetite—or capacity—for the kind of government spending that’s traditionally been used to boost economic growth, most economists agree that the next best thing is better pay, leading to higher consumption.

“I think there’s a consensus among most sane economists that we’re kind-of in what Keynes called a liquidity trap,” says Michael Burda, a professor of economics at Humboldt University in Berlin. “Anything you can do to stimulate demand from the real side of the economy will have strong effects.”