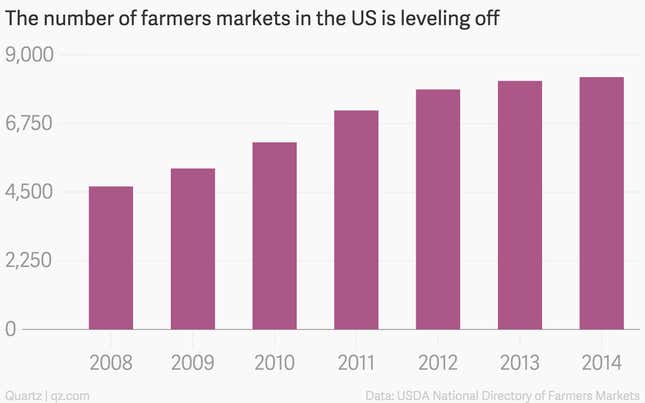

Is the locavore movement stalling out?

While the number of farmers markets listed in the US each year is almost twice as high as it was in 2008, the numbers have barely budged in the past two years.

Demand for local food is not slowing down by any means, though. What’s changing is that food producers are finding new (and in many cases more lucrative) ways of getting their goods into the hands of local consumers.

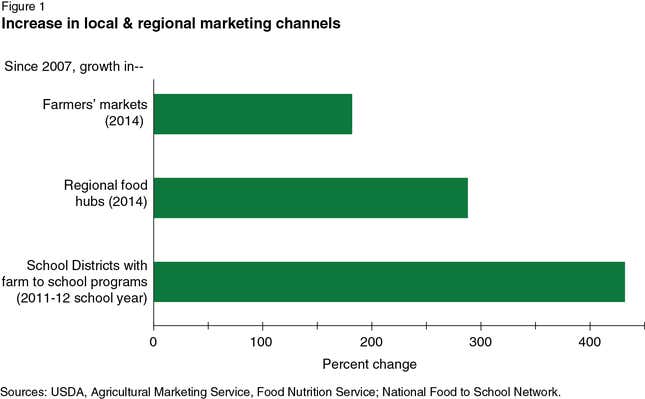

The appeal of farm-to-school programs

According to a recent USDA study (pdf) the number of farms conducting direct-to-consumer sales—including community supported agriculture (CSA) arrangements as well as farmers markets and independents farm stands—grew by 5.5% between 2007 and 2012. But sales from this category have stagnated. And that’s why NPR recently declared “peak farmers market” in the US, arguing that in some regions with too many markets, the consumer base for local food is being fragmented.

Indeed, driving 20 miles to an urban farmers market and spending the day wooing market-goers with free samples is increasingly, for many farmers, more trouble than it’s worth. Profit margins are fatter when a farmer sells to a local grocery store, restaurant, or school instead. This is partly why farm-to-school programs have become so popular over the past few years—as good as these arrangements may be for students, they’re also great deals for farmers.

The quest for one-stop shopping

Another alternative to farmers markets are food hubs, which provide the infrastructure for small farmers to reach a large network of potential buyers without the hassles of face-to-face marketing.

According to the USDA, a food hub can be a private business, a nonprofit, or a cooperative organization. “There’s no one model for a food hub,” the Associated Press wrote in December 2014, in a feature highlighting the operations of the Intervale Food Hub in Burlington, Vermont.

The Intervale hub is modeled after CSA programs in that customers pay a set fee to receive weekly bundles of foods sourced from 45 local producers. Consumers appreciate food hubs because they preserve the transparency factor that makes local food so attractive in the first place, the knowledge of exactly where each item comes from. The hubs also act as a one-stop shop for locally sourced items, which is a more convenient proposition for the busy consumer who, because she can’t get everything she needs from the local farmers market, shops there infrequently and still relies on traditional grocery stores for stocking the home refrigerator or pantry.

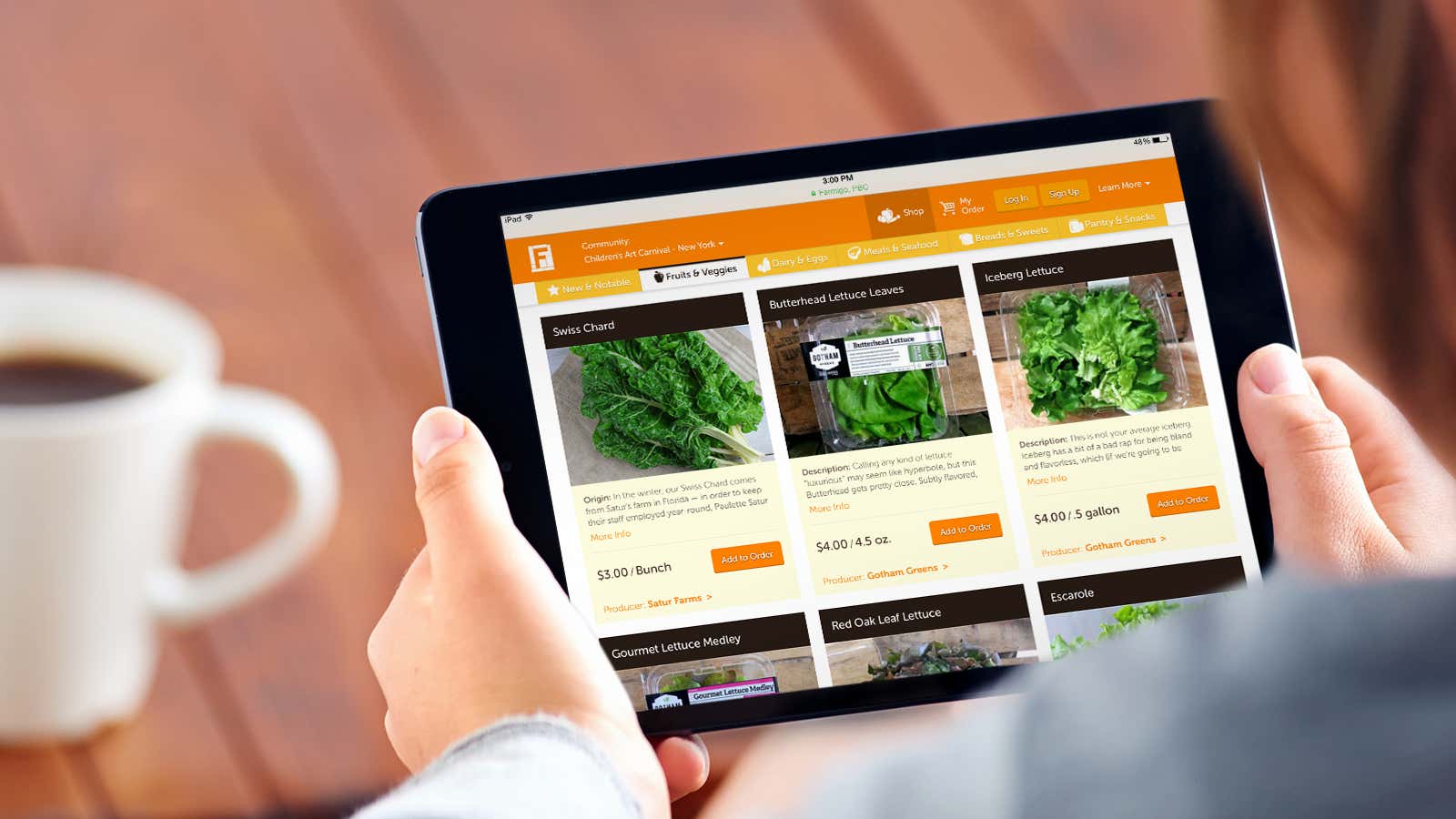

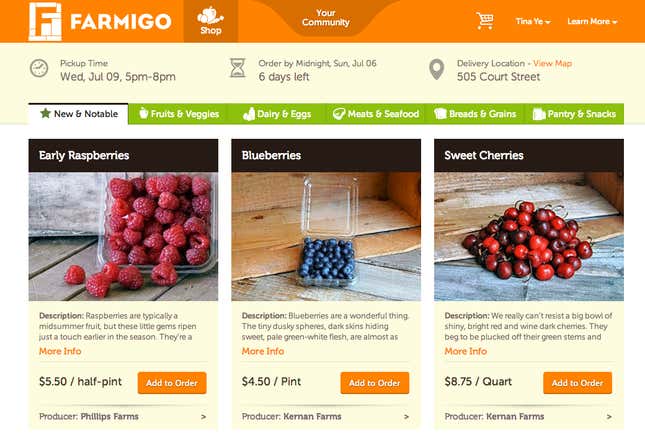

But even traditional supermarkets are becoming “unbundled” as more consumers look to delivery services such as Amazon and Instacart for their nonperishable, packaged foods, and turn to local producers for fresh foods, says Benzi Ronen, the founder and CEO of Farmigo. His Brooklyn, New York-based startup is part of a new generation of firms blending the farmers market, CSA, and food hub concepts with electronic commerce.

The e-commerce opportunity

On Farmigo, customers pick what they want from local farmers, after which the farmers harvest and prepare the goods requested, avoiding waste. And instead of door-to-door delivery, the goods are distributed at designated “pick-up points” in the customer’s neighborhood. This requires some leadership from at least one person in the neighborhood who agrees to host the regular grocery pick-ups (in exchange, the host gets discounts on his or her Farmigo orders, or a commission on everyone else’s).

Ronen, whose firm splits revenue with the farmers 60%-40% (with 60% for the farmers) says the food communities established on Farmigo are ”collapsing the food chain,” which he sees as essential in the food industry’s adoption of e-commerce. “If all we’re doing is taking the traditional food chain online, we’re missing an opportunity,” he says.