Speaking more than one language may confer significant benefits on the developing brain. Research has now shown that bilingual young adults not only fare better in the job market, but are also more likely to demonstrate empathy and problem-solving skills.

The fact is that American adults are largely monolingual English speakers, even those who began life speaking more than one language. Based on the latest research, it might be time to rethink the emphasis on monolingualism in the US.

Speaking two languages has advantages

Over the past decade, my research has focused on the academic, social, and civic development of immigrant youth, specifically the ways in which schools shape how these students experience learning, friendships, and their communities.

As a former elementary bilingual teacher, I saw how full proficiency in both languages offered students significant academic and social advantages.

What was missing, however, was the link between my students’ early social and academic edge, and their entry into the job market as young adults.

For all the research that supports childhood bilingualism, it is only recently that scholars have begun to understand bilingualism in adults’ professional lives.

Bilinguals show higher test scores, better problem solving skills, sharper mental perceptions, and access to richer social networks.

In addition, young bilinguals are able to draw support from mentors in their home language communities, and from the dominant culture.

These young people benefit from the wisdom of the adage: the more adults who invest in a child, the stronger she will be. The bilingual child benefits from being raised by two or more villages!

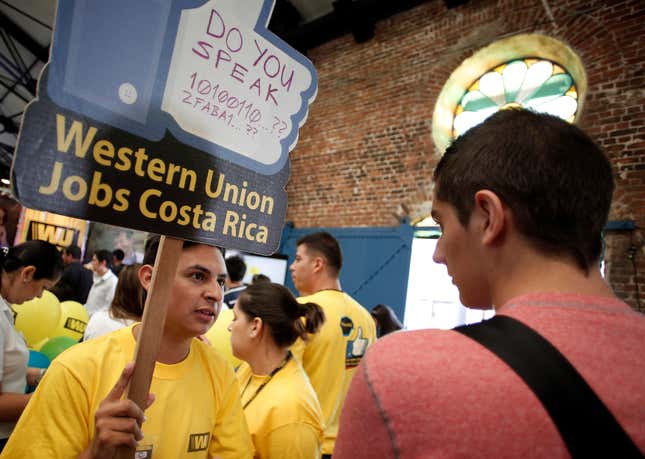

Bilinguals more likely to get a job

Not only are bilingual young adults more likely to graduate high school and go to college, they are also more likely to get the job when they interview.

Even when being bilingual is not a requirement, an interview study of California employers shows that employers prefer to both hire and retain bilinguals. Today, high-powered Fortune 500 companies hire bilingual and biliterate employees to serve as client liaisons.

Research links bilingualism to greater intellectual focus, as well as a delay in the onset of dementia symptoms. Frequent use of multiple languages is also linked to development of greater empathy.

Yet, despite research evidence, 4 out of 5 American adults speak only English.

English-only movement discourages another language

This is true for even those adults who began life exposed to more than one language. In the process of growing up American, many potentially bilingual children of immigrant parents lose their home language to become English monolinguals.

The powerful social and political forces behind the english-only movement testify to the perceived threat of bilingualism. Every day, schools and districts across the nation succumb to external pressures and cut bilingual instruction.

Historically, research investigating bilingualism and the labor market has employed US Census measures that do not distinguish proficiency levels in the non-English language.

Most national data-sets define bilingualism with very broad strokes that do not distinguish between: a respondent who speaks only Spanish, one who speaks Spanish and a little English, and a third who is fully bilingual and biliterate. Failure to capture this heterogeneity obscures any clear relationship between bilingualism and the labor market.

Only recently have NCES data begun to include measures of self-reported proficiency in the home language, while other, more immigrant-specific data-sets have begun to ask these questions.

Bilingualism related to higher learning

Of late, newer data and sharper analytical methods provide a far richer measure of bilingualism and individuals’ ability to read and write in non-English languages.

The ability to distinguish between oral proficiency in one or more languages and actual literacy skills in two or more has allowed researchers to identify an economic advantage to bilingualism—in terms of both higher occupational status and higher earnings in young adulthood.

The new data-sets measure bilingualism in younger generations who enter a labor market defined not by geographic boundaries, but by instant access to information.

Relationship between bilingualism and intelligence

Beginning in the 1960s, linguists began to find a positive relationship between bilingualism and intelligence.

Building on this work, researchers found that elementary aged bilingual children outperform their monolingual peers on non-verbal problem solving tasks.

Then, in the late 1990s, research emerged showing that even when controlling on working memory, bilingual children display significantly greater attentional control to problem solvingtasks than monolingual children.

Currently, researchers have begun to use data-sets that include more sensitive measures of language proficiency to find that among children of immigrant parents, bilingual-biliterate young adults land in higher status jobs and earn more than their peers who have lost their home language.

Not only have these now-monolingual young adults lost the cognitive resources bilingualism provides, but they are less likely to be employed full-time, and earn less than their peers.

Americans are beginning to grasp the cognitive, social and psychological benefits of knowing two languages.

Only 1 in 4 Americans can talk in another language

Historically notorious for their English monolingualism, a recent Gallup poll reports that in this nation of immigrants, only one in four American adults now reports being conversationally proficient in another language.

However, much more needs to be done if our nation is to remain a global leader in the next century.

Schools’ role in the maintenance and development of potential bilinguals’ linguistic repertoires will be critical to this process. Whether through bilingual instruction or encouraging parents to develop their children’s home language skills, what schools do will matter.

Today’s potential bilinguals will contribute more as adults if they successfully maintain their home language.

Educational research leaves little doubt that children of immigrant parents will learn English.

Where we fail these children is in maintaining their greatest resource: their home language. It’s something we should cherish, not eradicate.