The northern Ethiopian town of Adwa is the place my grandfather called home. It’s a small market town in the Tigray region, home to several churches where Ethiopian Christians of multiple sects congregate. My grandfather spoke of Adwa with pride and reverence, sometimes slipping into Tigrigna (one of the languages spoken in Tigray) as he recalled memories. The name “Adwa” always sounded so regal coming from his mouth, at once both strong and comforting.

For much of Ethiopia and its diaspora, Adwa’s significance is every bit as political as it is personal. In the bloodstained landscape that is Ethiopian history, Adwa is known primarily as the site at which the decisive final battle in the First Italo-Ethiopian War was fought. The Battle of Adwa, fought Mar. 1, 1896, was a violent clash between Italian imperial forces and the army of Ethiopia (known then as Abyssinia), composed of citizens who gathered from throughout the country to defend the nation’s sovereignty. The Abyssinian forces defeated Italy’s troops, ending the first Italo-Ethiopian War and Italy’s chances at formally colonizing what would later come to be called Ethiopia.

Long before the battle itself, both nations began to lay the groundwork for an Italo-Ethiopian conflict. Seven years prior to the events at Adwa, King Menelik II of Ethiopia signed the Treaty of Wichale (sometimes spelled “Wuchale” in transliterated Amharic, or “Ucciale” or “Ucciali” in Italian) with King Umberto I of Italy, essentially ceding the northern territories of Hamasen, Bogos, and Akale-Guzai (modern day Eritrea and northern Tigray).

The controversial 1889 treaty provided Ethiopia’s military with advanced European weaponry (namely, muskets and cannons), as well as financial resources, in exchange for control of the aforementioned territories. The treaty, signed before the formal start of the European colonial project known as the “Scramble for Africa,” was intended to align Ethiopia with Europe, while protecting the nation’s power by sacrificing only a handful of regions under its control.

One frequently contested article of the treaty stated, depending on whether it was read in Italian or Amharic, that Ethiopia’s government either must or simply could report to Italy when dealing with other foreign powers. Each country acted in accord with its respective translation, which naturally favored its own interests.

By 1890, Menelik had tired of the expectation to report to Italian officials; and he formally denounced the treaty in 1893. His wife, Empress Taitu Betel, is said to have played a tremendous role in refusing to cede sovereignty. Italy’s resulting attempt to extend a formal protectorate over Ethiopia, by means of force, culminated three years later in this now-famous 1896 defeat at Adwa.

The victory was, by all accounts, a landslide. On Mar. 2, 1896, The New York Times ran a story headlined, “Abyssinians defeat Italians: Both wings of Baratieri’s army enveloped in energetic attack.” The following day, the Times followed up with “Italy’s terrible defeat: 3,000 men killed, 60 guns, and all provisions lost.” The battle was widely reported in international media, stirring reactions in the West, ranging from shock to outrage.

Ethiopia’s victory had two fundamentally transformative historical and political consequences: the preservation of the nation’s formal sovereignty, and the cementing of Italy’s control over the region to be known as Eritrea.

The former consequence has reverberated throughout modern history. That an African nation could successfully repel an attempted European colonizer was not simply newsworthy. To Europeans, it was terrifying—cause to reevaluate military plans and colonial strategies. The purported inability of African peoples to respond with a sophisticated, machine-powered defense to European imperial encroachment was often in and of itself a justification for the violence of colonialism; the “white man’s burden” was to civilize people who were supposedly unable to civilize themselves.

For Italy, being humiliated on the world stage by “lesser” peoples constituted a serious blow to reputation and rank amid its Western peers. The ensuing conflicts between Italy and Ethiopia stem primarily in Italy’s pathological need to avenge its national pride: Mussolini’s 1935 invasion and subsequent occupation of Ethiopia was enabled largely by Italy’s continued presence to the north, but fueled almost entirely by festering, xenophobic shame.

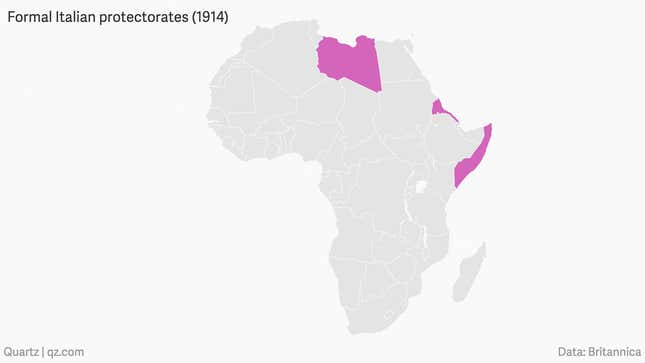

What Italy did not accomplish, however, was the colonization of Ethiopia, that which is defined by state-level, totalitarian domination, exploitation, and conquering of one party by another. Indeed, at no point has the nation of Ethiopia been considered a “protectorate” or “mandate” of Italy, despite erroneous Western interpretations of history. Rather, Italy’s occupation of Ethiopia mirrored a number of violent invasions that occurred within Europe itself over the course of the Second World War—mostly carried out by the Germans, but also the Italians in Albania, southern France, and parts of Greece. Generally, these expansions are not considered colonialistic in nature.

While Ethiopia’s status as an uncolonized entity remains disputed, the lingering, complicated effects of Italy’s invasions continue to manifest both within and outside of the country’s borders. Ethiopia’s victory at Adwa was, like most (anti-)imperial endeavors, fraught. Borne on the backs of the disadvantaged and disenfranchised, it ushered in renewed violence against ethnic minorities throughout East Africa. And yet, the battle, and the greater narrative of Ethiopia’s independence, are powerful symbols of African resistance to people of multiple ethnic, cultural, and national groups both on the continent, and off it.

Ethiopia’s simultaneous allegiance with and resistance to Europe created a complex, paradoxical strain of anti-African sentiment within the nation. Indeed, throughout various points in history, Ethiopians have seen themselves as being both un-African (or non-black) and a fundamentally, characteristically African example of rebellion.

This tension shows up elsewhere in the post-colonial imagination: “Ethiopianism” has often served as a basis for other black and African peoples’ visions of political and spiritual liberation from colonial forces, both formal and informal. Rastafarianism centers its religious focus on Emperor Haile Selassie I, the ruler of post-Mussolini Ethiopia and thereby a worldwide beacon of black-African hope for freedom from white persecution.

That Haile Selassie also annexed Eritrea is rarely mentioned. The conflict between the now-separate nations is often traced directly to Ethiopia ceding Eritrea to Italian control, the second major consequence of the Italo-Ethiopian conflict. Ethiopian-Eritrean relations continue to be abysmal, characterized by deep mistrust, frequent warfare, and economic sabotage. The Horn of Africa, also home to the beleaguered state of Somalia (the southern portion of which was once another Italian colony), is a hotbed of political violence, which cannot be separated from divides that occurred either under Italy’s rule, or as a result of evading it.

But almost 120 years later, Ethiopia’s victory at Adwa continues to inspire a unique sense of national pride within both the country and its widespread diaspora. The nation’s first hotel, named after Empress Taitu, is still one of Ethiopia’s most important historical sites. Mar. 1, the date of the battle, is celebrated internationally by Ethiopians and those invested in Ethiopia’s history. Art, photography, and film about the battle continues to document this powerful story.

To not grapple with Ethiopia’s complex relationship to colonialism does a disservice to Ethiopian (and indeed, African) history, as well as broader world-history surrounding it. The nation’s sustained fight for independence is a source of deep pride, shame, and confusion for people on all sides of the demarcation lines. It is, like the history of Europe’s own ever-evolving border relations, worthy of attentive study and critical analysis. There are countless lessons to be learned from Adwa and the stories its soil can tell; the measure of our collective knowledge will be our willingness to listen.