Humans can run blindfolded. We can navigate unpredictable paths without really seeing them. Though we teeter on the edge of falling with every walking or jogging step, usually we don’t.

“We have this inherent stability that keeps the whole thing going,” says Jonathan Hurst, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Oregon State University. Hurst designs machines that get around on two legs, and do it without vision sensors. People, he says, might assume the mechanics of upright travel are simple, because they’re so good at it.

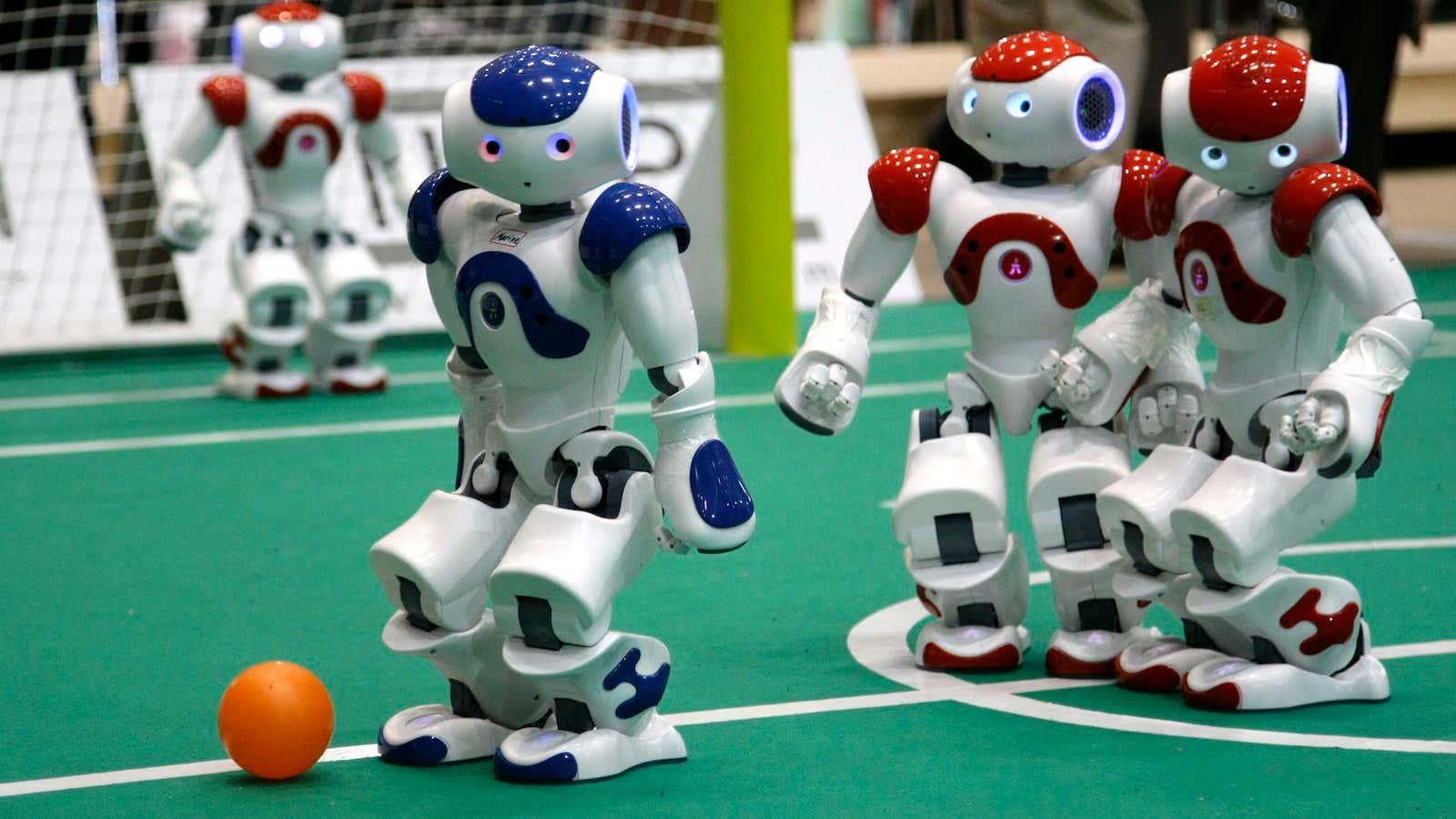

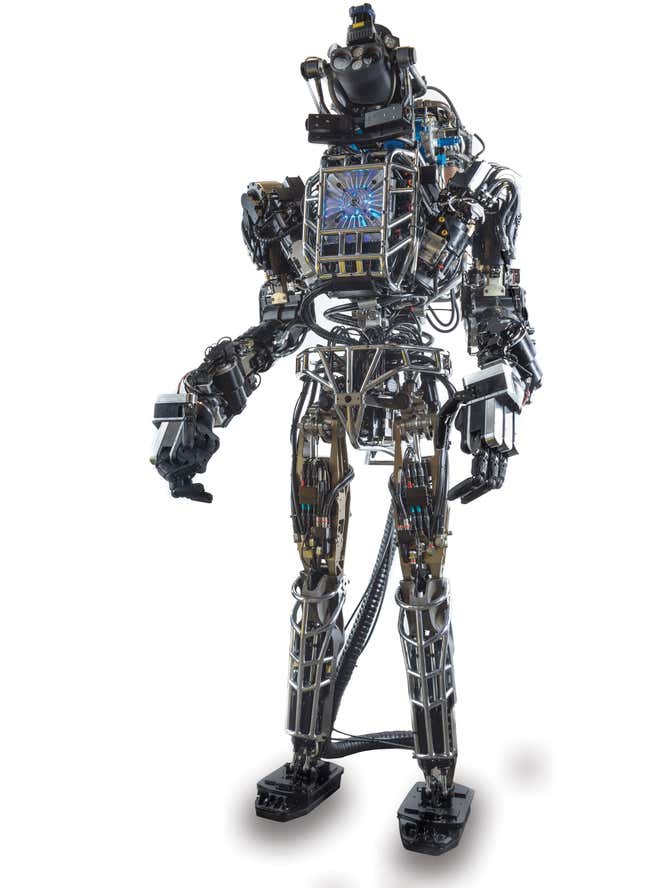

But primitive, two-legged locomotion remains one of robotics’ frontiers. The field is in high gear right now. In June, 25 teams from around the globe will vie for $3.5 million in prizes at the DARPA Robotics Challenge. Their charge is to build or program a prototype rescue ‘bot that could help in disasters. Most of the entries are humanoids.

Why, when bipeds are among nature’s rarest and most precarious designs, are so many set on mimicking them?

Robot-makers answer that machines shaped like people are best suited to navigate a world built for two legs. A robot that looks like a human would theoretically be versatile enough to climb ladders and stair, step over obstacles in its path, even drive a car. But scientists and scholars outside the field say there might be more to it.

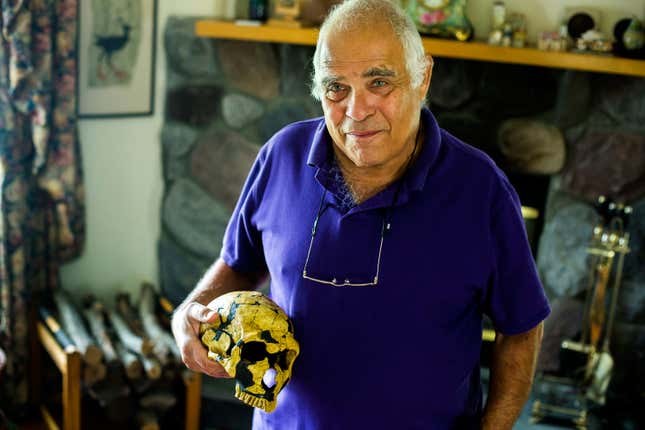

“Why design a human?” asks Milford Wolpoff, a paleoanthropology professor at the University of Michigan. “We’re not the fastest runners. We’re not the most stable. Natural selection works with what’s already there and we have ancestors who were not human.”

Our forebears lived in the trees like modern chimpanzees. They walked on branches and hung from them. The first hominid to mainly walk upright on the ground—a trait that separates us from the apes—lived about four million years ago.

Human bodies have changed over eons to accommodate this new way of traveling. Our feet arched. Our ankles and knees strengthened. Our leg bones cantered in. Our pelvises pivoted. Our spines curved.

But the evolution left scars.

“How many people do you know that have bad backs?” Wolpoff asks. He suggests that people might not be the best models for locomotion. If rescue robots need to carry things, why not give them four legs and two arms? Even three legs seem more stable than two. Or how about a tail like the theropod dinosaurs?

“If you start from scratch,” Wolpoff says, “you could make a much better self.” And in fact, that’s what Hurst did at first, designing robotic legs and gaits inspired by the way birds moved, with knees bent backwards like a flamingos.

But he found that there are non-mechanical advantages to building robots that look like humans. When collaborator Jessy Grizzle, an engineering professor at Michigan, asked Hurst to make it more human-like by turning the knee around, the result was a revelation: the robot was suddenly more interesting to strangers.

People care more about something when it looks human, Hurst says. Students get excited. Reporters write stories about it. “Then when you’re applying for grants, funders already have an introduction to your scientific claims,” he says. “And that’s how you keep a research program going. Never again will I build a machine from purely an engineering stance.

“Practically and pragmatically it worked better the other way,” says Hurst. “But people didn’t like it as much.”

Studies have demonstrated this. Robots, which embody the same spaces people do, might belong to a unique category that’s in between a person or animal and a thing.

Usually by the age of seven, children understand what’s alive and what isn’t, says Rachel Severson, a developmental psychologist at the University of British Columbia. They know how to classify trees even though they don’t move.

“But we’re finding that well beyond this age when they should have figured it out, they’re attributing internal states to the robots, like emotion,” Severson says. “They believe they can think, they can be friends and they deserve to be treated in a way that is moral.”

In her studies, even adults exhibited some of these behaviors. They seemed on some level to believe the robots she showed them have a will.

In some cases, this is what the robot-makers intended, Severson says.

“I wouldn’t say this is true for all of them, but for some roboticists I know, there’s a real curiosity around recreating the human form and the technical challenges it involves,” Severson said. “There’s a real curiosity around creating life.”