The web is fading.

Not long ago, those were fighting words. In 2010, when WIRED ran a cover story burying the web (while praising the internet), David Pogue, then technology columnist for the New York Times, called it “irresponsible” and “total poppycock.” Now, as data continue to pile up showing mobile apps surpassing desktop web (and far surpassing mobile web) as our on-ramps to the internet, saying the web is dying is like saying flip phones have seen better days.

True, proclaiming the death of any technology is a tricky business. Mainframes have been dying since 1988. Technologies don’t die outright so much as go into eclipse, each new paradigm moving its predecessor from a dominant role to a niche one.

Better to think of the web as a bloated monarchy. It’s ruled for a good long time, but the mobs at the castle gate waving smartphones are getting louder and harder to ignore. And now they’ve got something on their side that looks like it just might topple the monarchy for good.

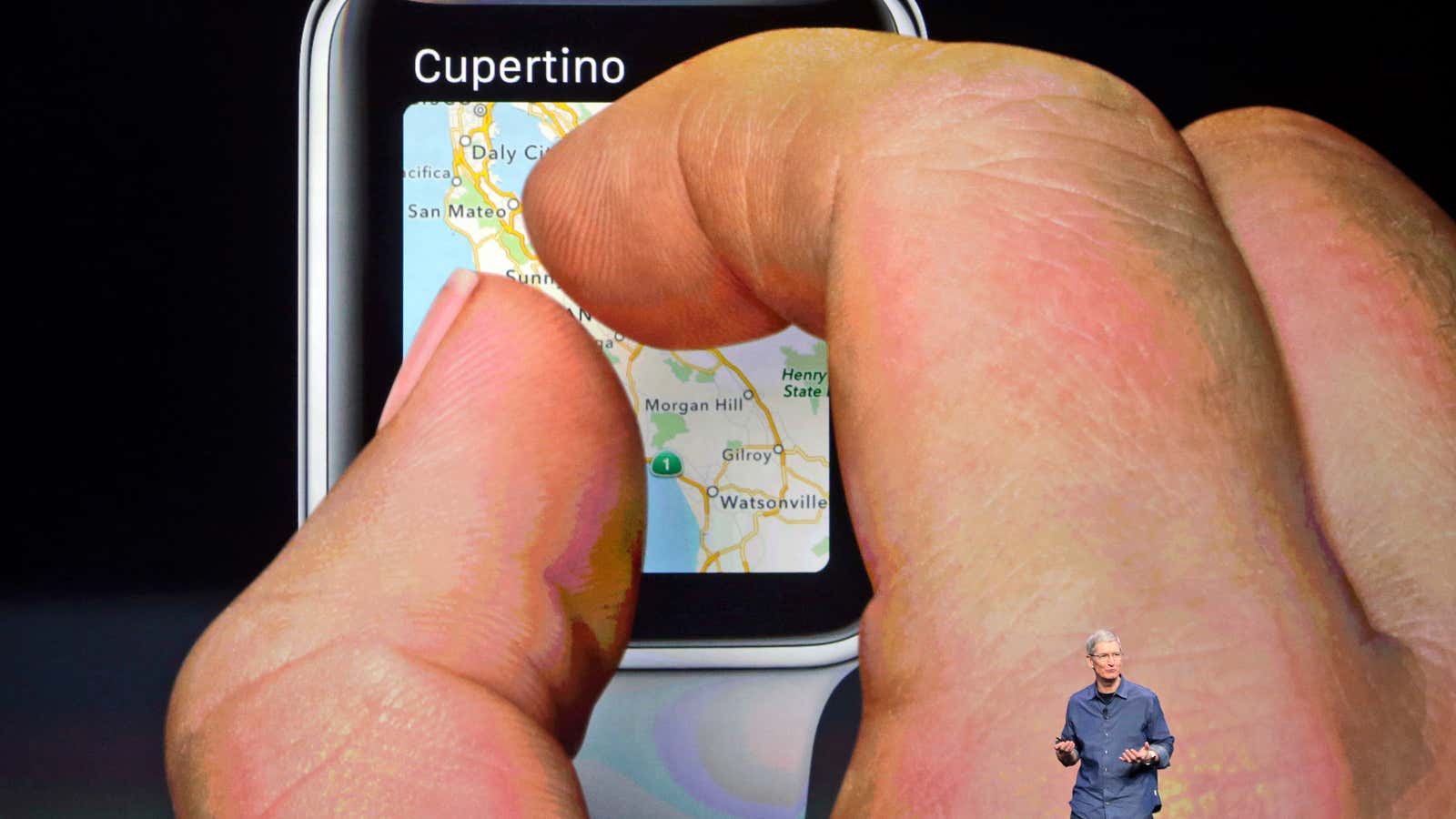

Enter the Apple Watch.

App <> Web <> Internet

The Apple Watch marks the next, probably last, step in the downfall of the web. Or more precisely, the downfall of the web as commonly understood: that HTML medium which has spent the last two decades dominating the way we buy, share, search, learn and collaborate.

To see why, it’s important we take a moment to clarify our terms. Any declaration of the web’s decline runs immediately into confusion over what is meant by “the web.” So:

- Web: that interface of markup language that runs in a browser and hides the pipes beneath–what the Wall Street Journal’s Christopher Mims (in another good piece about the death of the web) calls “that thin veneer of human-readable design on top of the machine babble that constitutes the Internet.”

- Internet: the pipes, the tubes, the vessels–the hardware and software infrastructure that ferries digital data from one point to the next and basically makes our economy run.

- App: those smart, personal, purpose-built units of software we call up from our mobile devices to do just about everything under the sun. For our purposes, I’m excluding web apps–apps that launch in the mobile web browser and are generally ignorant of the underlying device–for reasons that will become clear.

The chief point here is that the “web” and the “internet” are two different things, however much we may conflate them. In the web world, this is a distinction without a difference. Why? Because both the user interface (HTML/web) and the backend data/logic (server/internet) are tightly coupled.

But in an app-driven world, that coupling is loosened dramatically. The client-side user interface and the server-side data access and logic are built to operate with a much higher degree of independence from the other. In many ways, apps harken back to the client-server paradigm that predates the web. (Such is the nature of tech evolution: each new thing is really a variation on something past.)

To repeat: it’s the web that’s in decline. The internet ain’t going anywhere any time soon.

Mobile’s Killer App: User Experience

What began the toppling of the web? The mobile app. And the reason is pretty simple: apps deliver a much better user experience.

The web is a dumb terminal. That may sound like a cruel judgment on the technologies that have spent the last two decades upending the way we do things, but it’s true. A web page or web application knows little more than what you tell it. Sure, there are cookies and other mechanisms for remembering people (and tracking them around the web). But compared to mobile apps, these are primitive–frequently annoying–instruments for understanding what a user is after.

By contrast, consider the mobile app. A good app can recognize where you are, what (or who) you’re near, whether you’re moving or standing still, which direction you’re pointed–all without a single input from you. Mobile apps provide an automatic contextual awareness that web applications can only dream about. It’s the choice between a dumb terminal and an anticipatory, participatory portable assistant.

Mobile apps have other natural advantages. For one, they can work offline. Web access assumes a steady network connection, something that can be hard to come by in a world of tunnels, elevators, air travel and other dead spots.

Apps are also small. The modest size of the mobile device screen enforces a kind of productive constraint on app design. The best apps are clean, simple and purposeful. They have to be–there’s not enough screen real estate for dozens of fields, buttons or other feature-bloat. (This is to say nothing of pop-ups and banners and all the other digital panhandling that has come to define the average web experience, and which the New York Times’ Farhad Manjoo points to as another reason for the web’s decline.)

In other words, mobile devices aren’t merely a smaller, more portable screen by which to access web pages. They’re an evolution in connection and interaction. While the web is all about discoverability–aggregating and orchestrating content sources via its essential paradigm, the hyperlink–mobile apps are all about knowing what we want, sometimes even before we know it ourselves.

Apple Watch As Tipping Point

With wearables and other connected “Things,” the way apps differ from their web ancestors becomes even more dramatic. Consider some of things happening:

- Screens can no longer be assumed. They’re either absent, or are shrunken to such a degree that interactions must be driven by gestures and environmental clues, rather than the user touching or clicking (to say nothing of typing). As Jeffrey Hammond at Forrester Research writes, these new form apps “must project a digital reality that meshes with physical reality instead of substituting for it.”

- App boundaries are dissolving. Today we understand apps largely as icons on our devices, standalone entities that we open to perform various tasks. But already the boundaries among apps are blurring. Apple’s Passbook, for example, aggregates tickets, coupons, boarding passes and other certificates from third-party apps, expanding the footprint of a given app outside its icon.

- Apps and operating systems are getting cozier. If the boundaries between apps are blurring, so too is the boundary between app and the underlying OS. With iOS 8, Apple made both Touch ID and Apple Pay available to any third-party app. In this way, binding the app to the operating system promises better, more powerful features to app users. (Of course, it also works to bind apps and their developers more closely to Apple.)

These change mark an evolution from today’s mobile apps, and an even starker break from web applications. If the current mobile app paradigm stretches the legacy web approach beyond what it was intended for; the app paradigm for wearables and other devices will break it permanently.

It seems fair to say that many companies still don’t perceive apps as a sharp break from the web. There remains a good amount of “making do”–porting existing web applications to the smaller screen size and calling it a day. This is unfortunate, but understandable. Not only are apps designed and developed differently from web, they require new means of connecting to backend data, all of which demands skills that today are in much shorter supply than traditional web ones.

But with the Apple Watch, such “making do” won’t work. The tiny screen size and limited interface options won’t allow for merely shrunk-down versions of web applications. The Watch’s apps will need to be true apps: things built with an awareness of and commitment to the underlying device capabilities and limitations.

Why haven’t the wearable devices currently available forced this sea change? Simply put, because they weren’t built by Apple. Apple is seldom first to any category, but where it moves it dominates. Early demonstrations–a beautiful collaboration of hardware and software, joined to Apple’s ecosystem and channel clout–suggest another Apple product that will redefine its market.

The Future of the Web: Not Dead, But Extremely Sleepy

The web won’t disappear. Its properties of discoverability and its capacity for aggregating and distributing content will see to that. But it won’t be what it’s been, the Goliath around which virtually every digital interaction is built. Instead, the web of the near future will function chiefly as a collection of signposts to apps. We’ll continue find goods and services via the web, but we’ll engage those providers via their apps; their web page will be little more than a billboard for their app.

But the internet–that will continue to thrive. Rather than an engine for serving HTML pages, it will become a hive of data endpoints (APIs), to be orchestrated as the services that drive our apps.

For companies and indie developers alike, the way forward means forgetting the previous decades’ assumptions around screen real estate, keyboards, even reliable network connections. The mobile paradigm means APIs, orchestrated into apps that are optimized for the devices they run on. That’s the bold new realm ahead.