There is a roaring trade in Venezuelan goods along the country’s border with Colombia. That is in stark contrast to the general malaise of the economy in the rest of the country.

By many measures, Venezuela’s economy is the most sickly in the world. From the value of its currency (sinking), to its inflation (scorching) and GDP (shrinking), Venezuela ranks at or near the bottom of just about every important financial indicator out there, performing worse even than Argentina, Greece, or Ukraine.

The battered bolívar

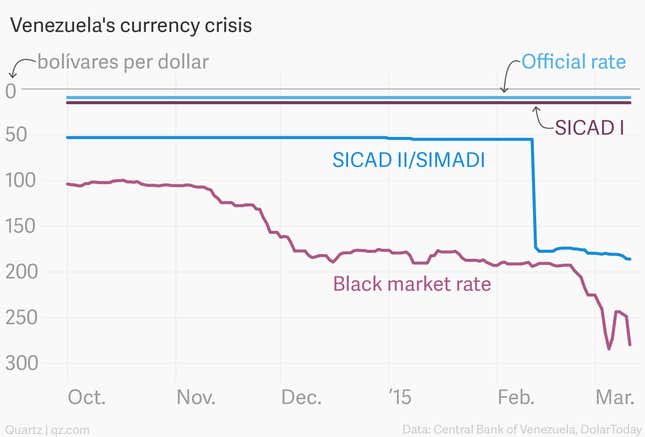

The most striking sign of the country’s financial crisis is its rapidly weakening currency, which has lost more than 60% of its value against the dollar on the black market over the past six months. This is not immediately apparent in official figures. Venezuela’s convoluted three-tier exchange system suggests that the bolívar is much stronger than this, thanks to strict currency controls—which is why nobody believes the official figures.

That’s where the smuggling on the border comes in. Because the government fixes prices for a wide range of goods according to fixed exchange rates, it pays to buy cheap stuff in Venezuela and sell it in Colombia at a significant markup. Meanwhile, shortages of everything from critical medical supplies (paywall) to toilet paper makes life for ordinary Venezuelans miserable, even as the country struggles to pay for imports with its increasingly worthless currency.

Last month, an attempt to loosen restrictions on foreign exchange led to a huge devaluation in the bolívar. Although the new system, called Simadi, lets individuals access dollars more freely than before, only around 10% of the dollar trade takes place on the exchange, according to Moody’s. Three-quarters of dollars are still traded by the government at the laughably overvalued rates of around 6 and 12 bolívares to the dollar.

Eye-watering inflation

To add insult to injury, the US recently announced financial sanctions against a clutch of Venezuelan officials, citing human rights abuses, persecution of the press, public corruption, and much else besides. Venezuela’s government immediately denounced the move, taking it as yet another excuse to warn of an imminent US-backed coup.

This was a welcome distraction from the sky-high crime rates and spiraling inflation that bedevils the increasingly isolated country. Consumer prices are now rising by nearly 70% per year, the highest rate in the world.

A deep depression

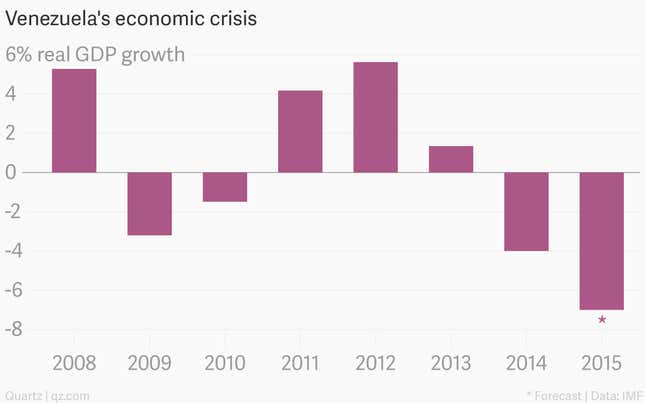

The ”Bolivarian” socialist economic model espoused by the late president Hugo Chávez and extended by his successor, Nicolás Maduro, has failed to diversify the economy from its overwhelming dependence on oil, which accounts for some 95% of export earnings. Thanks to the fall in crude prices, the government in Caracas now faces a financing gap of more than $30 billion both this year and next, according to Moody’s. Some analysts believe that the combination of lower oil prices and government spending promises could push Venezuela into default as early as this year.

The IMF recently slashed its forecast for economic growth in the country this year, to a 7% decline in GDP on top of an estimated 4% fall last year. Aside from some enterprising traders near the Colombian border, few Venezuelans are benefiting from the Bolivarian revolution.