AUSTIN, Texas—Perhaps the most surprising and important product debuting at SXSW Interactive this year is a personal protective equipment (PPE) prototype for health care workers dealing with Ebola, a tangible result of the U.S. government adapting the culture of innovation and design thinking so key in the startup world.

This morning, a team from the U.S. Agency for International Development demonstrated the traditional Ebola suit and the new suit in a preview for Quartz. (The suit is being shown to the public for the first time today at 3:30 p.m. at the JW Marriott.) The unlucky Alma Chapa, an adviser to USAID, wore the hot, stuffy old suit, taunted by an iced Starbucks coffee that she was not able to drink due to her facemask.

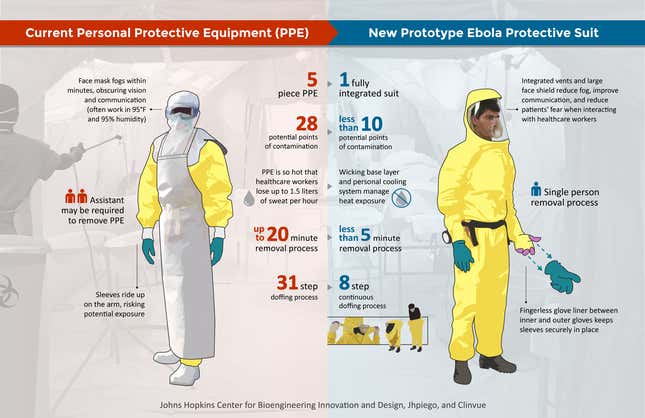

The two biggest issues with past PPEs were the tendency for workers to overheat and the high risk of contamination when removing the suit. Even as we sat in an air-conditioned hotel, Chapa’s goggles were fogging up and she was visibly uncomfortable after a half hour. The traditional Ebola suit is made up of many parts; the one worn by Chapa is typical of Doctors Without Borders’ outfits. A yellow coverall, topped by a Tyvek hood, a breathing mask and goggles, two sets of gloves, plus a heavy-duty splash guard, takes two people and about 20 minutes to put on. Every bit of skin has to be covered, and the suit is taped at the wrists and ankles. That means the suit also takes about 20 minutes to take off — after merely 45 to 60 minutes of wearing it, lest the health care worker overheat — and that must be done solo. “You’re at risk of heat stroke. The doctors have to calculate how much time they have enough time to get out of the suit,” says Wendy Taylor, director of the Center for Accelerating Innovation & Impact at USAID, and suit removal is when there’s the greatest risk of Ebola exposure.

Another issue with old suits is an effect called respirator waterboarding, where the sweating medical worker saturates the breathing mask, which then feels like drowning. “Just the pressure of glasses on your nose is an annoyance, like having a pebble in your shoe,” Chapa says. “Breathing through the mask feels normal but restrictive. For me, there’s also panic because I’m claustrophobic. Then add that to the stress and fear and heat.”

The only part of the worker visible is the eyes, and sometimes not even then if fog sets in, so doctors tend to write their names on their hoods so others can identify them. The entire outfit costs on average about $70—the boots, aprons and goggles can be used again after being dipped in bleach and air-dryed, but the rest is burned.

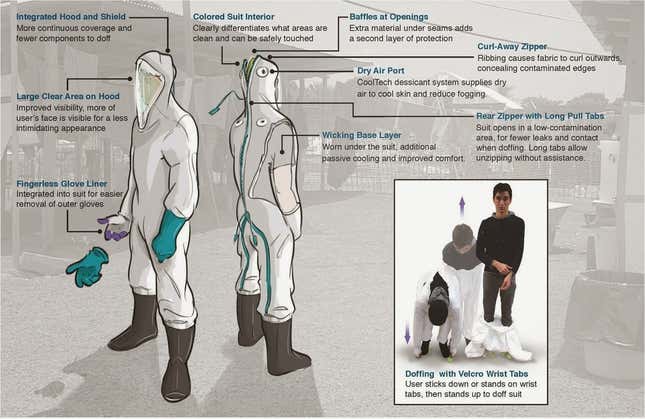

The new suit—designed by the Johns Hopkins Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design, innovation consultancy Clinvue, and Jhpiego, a global health organization and Hopkins affiliate, and demonstrated at SXSW by Matt Petney, a JHU biomedical engineer—is one piece, with improved vision and ventilation and a quick removal process.

The hood has a huge plastic panel for a full view of the wearer’s face, and an antifog breathing apparatus. Elastic straps at the fingers keep the sleeves anchored on the wearer’s wrists and allow for outer gloves to be pulled off when doffing the suit. Straps at the back of the head let a person rip the suit off, with a tearaway zipper and two velcroed ties at the front that you lean forward to step on and pull the suit off as you curl up like a snake shedding its skin. The suit is yellow on the outside and white on the inside, so it’s easier to tell which parts might be contaminated. The material for the next-gen Ebola suit is Tychem QC, a Tyvek fabric with a polyethylene coating produced by Dupont. The goal is for the suit to cost about the same as existing PPEs, and USAID is in talks with a manufacturing partner to be announced.

USAID is working with the CDC and DOD to test for the suit’s cooling capability and penetration testing, but user feedback was also vitally important. Initially they thought perhaps they should be developing a suit that could be work for a five- or eight-hour shift. But doctors in the field said the longest they can stand to be in the hot zone of the ETU — simply because of the emotional stress — is an hour or two.

The Johns Hopkins suit is one of the 15 awardees of USAID’s Ebola Grand Challenge. Sponsored with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Defense Department, the challenge is just the latest in a string of grand challenges that invite the public to take part in fighting global problems and will lead to about $9 million in funding. With the fight against Ebola far from over, but recently overlooked for new news, the USAID team hopes to get the new suit in production in the next few months, and some of the design features of the PPE are already being integrated into other suits.

“Traditionally people think of government and innovation as an oxymoron, and we’re out to change that thinking,” says Ann Mei Chang, executive director of USAID’s Global Development Lab. Chief Innovation Officer Steven VanRoekel says putting out RFPs tended to get proposals from the same players—opening up the problem solving to the public broadens the ideas.

Just in the past few weeks, the last patient with Ebola in Liberia was sent home and schools have reopened. “But it’s not done until we reach zero in all affected countries,” Taylor says. “The road to zero can be a long and bumpy one.”