They got him in the end.

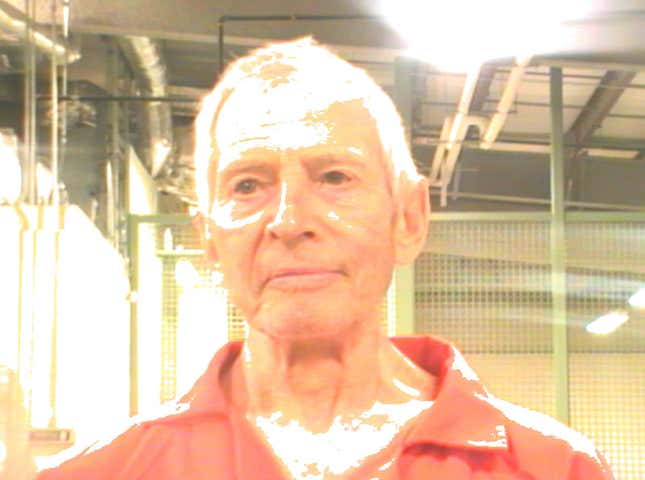

Robert Durst, the scion of a New York real estate family who was long suspected of murder in three states, was arrested hours before HBO aired the final episode of a documentary about the killings. It was not a coincidence. He gave extensive interviews for The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, and appeared to have implicated himself in the process. Police were reportedly concerned the show’s conclusion might cause him to flee.

Most viewers were undoubtedly aware of the day’s events, even if HBO did not acknowledge them in the broadcast, but they could not have expected what was to happen on screen.

Confronted with damning evidence that seemed to tie him to the murder of a close friend in Los Angeles, Durst could barely muster a burp and a shrug. Alone but still mic’d in a bathroom after the interview, however, he muttered to himself what could only be taken—by the audience, if not a court of law—as a confession.

“There it is,” he was heard saying in audio captured by the microphone still attached to his lapel. ”You’re caught.”

It was easy to picture Durst, whom viewers had gotten to know well over the course of six episodes, staring at himself in the mirror, rattled by the confrontation with the filmmaker, Andrew Jarecki.

“You’re right, of course,” Durst’s soliloquy continued. It was as though he were rehearsing better answers to Jarecki’s questions, or to himself. “But you can’t imagine. Arrest him. I don’t know what’s in the house. Oh, I want this. What a disaster. He was right. I was wrong. And the burping. I’m having difficulty with the question.

“What the hell did I do? Killed them all, of course.”

The appeal of true crime lies, of course, in its truth. Every new detail complicates the narrative, expanding the set of possible outcomes rather than conveniently narrowing it to a simple answer. The debris of truth left behind by these stories rarely satisfies with notions like closure or justice—in fact, one lesson of the genre’s classics is that resolution is a trope reserved for fiction.

Jarecki had his go at convenient narratives in his 2010 film All Good Things, a loosely fictionalized account of the disappearance of Durst’s wife. The movie all but convicted the main character, which is apparently what motivated Durst to sit for interviews with Jarecki and discuss the crimes in detail for the first time.

“I will be able to tell it my way,” Durst explained to the filmmakers in an early episode.

The Jinx hardly attempted to tie a bow around reality. Through most of its first four episodes, the theme was how confounding the facts remained. Durst was the only suspect in all three killings. He was tried in one of them but, after admitting to chopping up the body and fleeing, he was acquitted by a Texas jury based on his claim of self-defense.

The best evidence tying him to any of the other crimes seemed merely to be a confluence of very strange events and behavior—enough to make for compelling television, but well short of a satisfying conclusion. That messiness came through clearest in the observation, repeated by several interviewees, that if Durst were innocent, he is a supremely unlucky innocent man.

It was a refrain familiar to anyone who listened to Serial, the popular podcast that last year cast doubt on the outcome of an old murder case in Baltimore, to which The Jinx is frequently compared. Having constructed a narrative around the search for truth, the podcast faced an impossible burden. It was, after all, limited to what reality would bear. That led to a surreal scene in which the main character, Adnan Syed, in jail for the crime, had to stand in for an expecting audience in an interview for the finale.

“If you don’t mind me asking,” he said to Sarah Koenig, the lead investigator and host of the program, ”you don’t really have no ending?”

She did not, which was less a disappointment than an acknowledgement of what everyone knew (or should have known) to expect from the start. So it was for The Jinx, as well, until Durst went into that bathroom.

There were hints in previous episodes that maybe this was not going the way of most true crime. The documentary dwelled on Durst’s blunder, in 2001, of shoplifting a chicken sandwich while on the run from police. In the fourth episode, he was caught making vaguely incriminating comments on an open microphone. And in the fifth, he stood awkwardly outside buildings managed and owned by his brother, Douglas Durst, as though he wanted to be arrested. (He was, for trespassing, though he was eventually acquitted of those charges, too.)

“Sometimes people have said, ‘Does Bob know what you’re doing?'” the filmmaker Jarecki said recently. “And I say, ‘It was his idea.'”

If The Jinx was an elaborate exercise in self-destruction, then Durst certainly succeeded. He was arraigned in New Orleans and expected to be extradited to Los Angeles to face charges for the 2000 murder of Susan Berman. In the meantime, Jarecki was busy distancing himself from the law enforcement aspect of his work, though he has said (paywall) the filmmakers began speaking with Los Angeles investigators in early 2013.

We are drawn to true crime narratives because they actually happened and, thus, might have more honest things to say about the human mind. But in The Jinx, the dichotomy at the end was not between fiction and truth. Instead, it laid bare the difference between the lies we tell everyone else and the truths we are only willing to confront when alone in front of the mirror.