Frank Bruni’s new book, Where You Go Is Not Who You’ll Be, argues that the college you attend doesn’t really matter so much. The coveted Ivy League—and the wider range of elite schools—have more applications than ever before, but Bruni recommends that anxious students and their status-obsessed parents caught up in the admissions madness should calm down and relax—the school you go to cannot define you.

Which is, of course, both trite and true. In life, you are what you make of each opportunity. Yet Bruni himself, an influential New York Times columnist and prominent member of the US elite, makes an argument that somewhat contradicts his own educational history. After all, he graduated from a top public institution—The University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill—and an Ivy League graduate school—Columbia University.

Would he be where he is today if he had just chosen a college or graduate school at random?

Bruni told The Washington Post that he decided to write the book “because of the constant chatter among his friends who have kids in high school and among his nieces and nephews ‘all whipped up in a frenzy’ over where to go to college.” He went on to say: “I was watching this and comparing it to my own life and the successful people I know… I wondered if there was anything in their résumés, a uniform attendance at a few select schools, and I didn’t see it. It wasn’t the case.”

To Bruni’s credit, he does conduct some research to support his point. For example, he examined the American-born chief executives of the top 100 companies in the Fortune 500 and noted that roughly 30 went to an Ivy League school or equally selective institution.

However, why stop at 100? Why not examine the entire Fortune 500? That is, in fact, what I did in my research (pdf), published two years ago. And in an extended analysis from 1996 to 2014, I uncovered that roughly 38% of Fortune 500 CEOs attended elite schools (see the paper for the full list) for the last two decades.

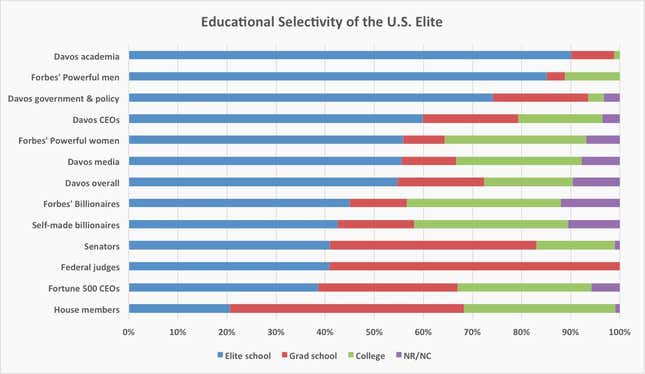

But to more fully evaluate Bruni’s claim, why not examine the US elite more broadly? This is exactly what I did. The following data in the graph below are taken from another research paper which can be found here (pdf). I looked at the educational backgrounds of US Fortune 500 CEOs, federal judges, senators, House members, attendees at the World Economic Forum in Davos (which included CEOs, journalists, academics, and people in government and policy), and the most powerful men and women according to Forbes. The blue bars indicate the elite school percentage (undergraduate or graduate school). The red bars indicate the graduate school percentage not included in the elite category. The green bars indicate those who graduated from college independent of the other two categories. And the NR/NC category indicates people who did not report or had no college.

One might argue that the Fortune 500 CEO elite school percentage of roughly 38% is not very high. But this value should be taken in the broader context. Note the purple bars, which show that nearly everyone in the US elite graduated from college. This flatly contradicts the stories glamorizing college dropouts—such as Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg—who both were accepted by and attended Harvard. Next, it’s interesting to note that 44.8% of billionaires, 55.9% of powerful women, 63.7% of Davos attendees, and 85.2% of powerful men attended elite schools. Finally, 55.6% of the journalists who attended Davos went to elite schools. I conducted my own analysis of the data on The New Republic masthead, suggesting that roughly 64.2% attended elite schools. Data on the New York Times was not systematically available, but it is unlikely to be much different, and may even be more select given its reputation.

Based on census and college data, I estimate that only about 2% to 5% of all US undergraduates went to one of these elite schools. That makes all these US elite groups well above what you would expect in the general population. And this doesn’t even include the percentage who went to a “non-elite” graduate school.

Bruni may be right to criticize the fixation on elite schools, as there are only so many slots at these institutions—so most students (and their parents) by definition simply will not be able to gain access. But to suggest that where you go to school doesn’t matter makes little sense. For students throughout the range of colleges and universities, going to a more recognized school is likely to help open doors for their future—at least in the current US educational and occupational structure. This, of course, doesn’t mean that it is necessarily the elite school education or experience that is the driving factor. Among other things, eventual success could be attributed to individual characteristics such as brains and motivation, which unlocked the door to admission to begin with.

But among people similar to Bruni’s social and family circle, who appear fixated on which college to go to, perhaps their hunch is not wrong. This is likely because many of these people know that where they went to school opened doors for them, regardless of the quality of the education they received—and that is why they want their kids to have those same opportunities. As members of the US elite, they want their kids to at least match if not surpass them, to have an advantage in life, and to reap the enormous benefits that come with that privilege. As my research shows, if you want to become a member of the US elite, an elite school (or grad school) appears to improve your chances.

As Gregory Clark explained in The Son Also Rises: “Most parents, particularly upper class parents, attach enormous importance to the social and economic success of their children. They spare no expenditure of time or money in the pursuit of these goals. In these efforts, they seek only to secure the best for their children, not to harm the chances of others. But the social world only has so many positions of status, influence, and wealth.”

Asking whether parents should send their kids to the Ivy League if they qualify raises an important discussion of US cultural values, something William Deresiewicz already thoughtfully and persuasively argued against in his book Excellent Sheep. Bruni is right that success in life can be found through many paths and educational institutions—and his message that even if you don’t get into the college of your dreams you can still achieve them is positive, uplifting, and true. Parents certainly can become overly concerned with the outcomes of their children. But parents often think of increasing the likelihood of success of their children. So when it comes to college admissions they (and their kids) might be acting in an entirely rational manner given the credential-obsessed society we live in today.