“What is real?” asked Michael Abrash, Oculus VR’s chief scientist, posing that very existential question to Facebook’s annual gathering of developers. (Facebook bought the virtual reality startup for $2 billion last year.)

He found the answer in a line from the 1999 sci-fi movie The Matrix: ”If real is what you can feel, smell, taste, and see, then ‘real’ is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain.”

In an effort to deconstruct the complexity of virtual reality, Abrash pointed out a number of limitations to human sight: Our eyes have blind spots, have only three color sensors, lack blue photoreceptors in the center, and can only see a fraction of the 360 degrees around us. To compensate, the brain often kicks in to fill in any gaps by using contextual clues, such as lighting. “It’s fair to say our experience of the world is an illusion,” he said. “What that means is virtual reality done right truly is reality as far as the observer is concerned.”

To prove his point, he demonstrated the following optical illusions. (“It’s one thing to listen to words about how we infer reality but it’s another matter of fact to experience it.”)

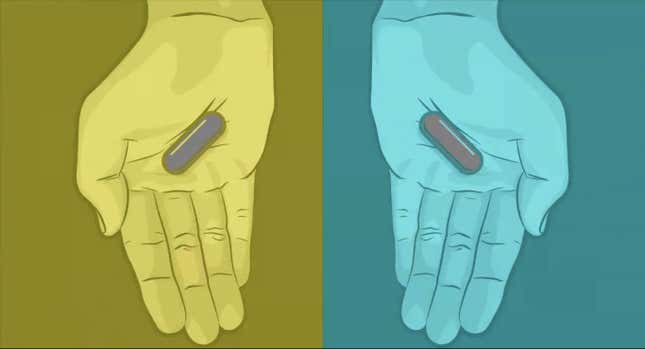

Red pill or blue pill?

Abrash begins with a very Matrix-esque example: blue pill or red pill? Neither. Turns out both of these are the exact shade of gray, but their surroundings alter our perception and make us think they’re blue and red.

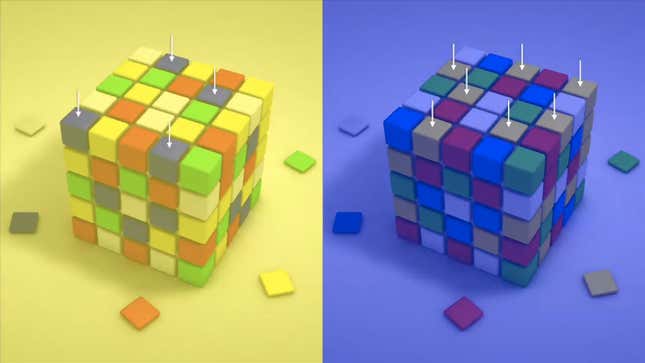

Rubik’s cube

The blue squares on the left Rubik’s cube and the yellow ones on the right cube are actually the same shade of gray.

Moving paper T-rex

The paper dinosaur appears to be moving. But at the 1:32 mark in the video, you can see how its clever construction has fooled the eyes. Yet knowing that, you still perceive it as moving. “In short, reality is what the brain wants it to be,” said Abrash.

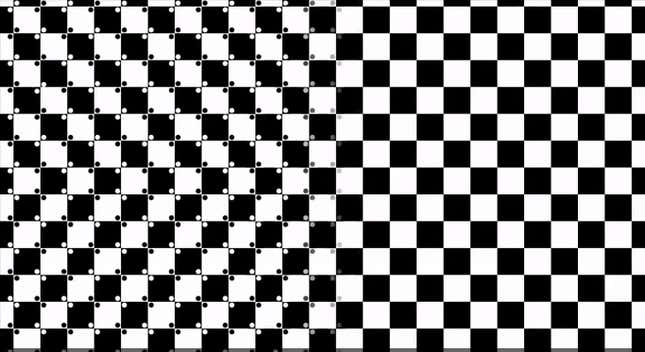

Warped checkerboard

Double check with a straight edge if you have to, but the horizontal and vertical lines above are straight. It’s the dots that make them appear warped.

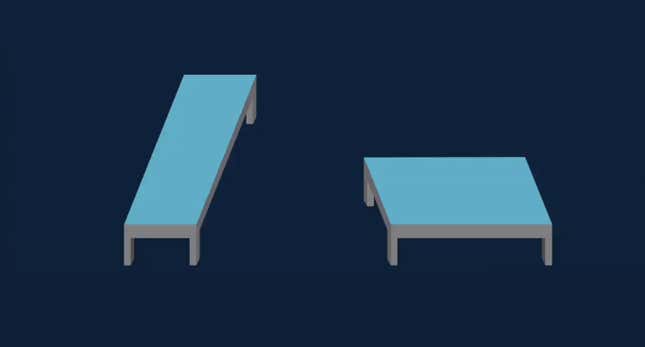

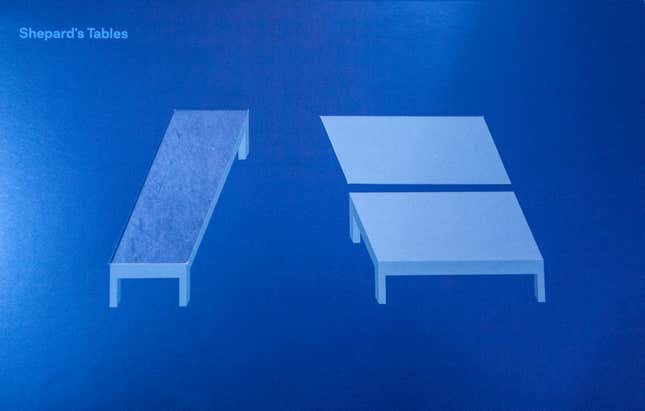

Which table is longer?

They’re actually the same size. To prove it, Facebook gave attendees a smaller version on paper, where the shape of the left table popped out so it could be placed on top of the right table.

Bar vs. far

This video demonstrates the McGurk effect, or how visual context can override auditory input. Even with an audio track repeating “bar” over and over again, people hear “far” when they see the woman’s lips pronouncing the letter f.

Spinning balls

The black-and-white spinning balls rotate in a counter-clockwise direction, but once you focus your eyes on either the red or yellow circle, it’ll appear as if the black-and-white balls rotating around the other circle are moving in the opposite direction.

White or black square?

In this instance, the brain is using lighting clues to determine the color of the square underneath the table, which is the same shade of gray as the black ones on the side. (We double checked with the eyedropper tool on Photoshop.)

That dress

Officially, it’s black and blue, but many people perceive it to be gold and white due to the lighting (and possibly age).

These examples help illustrate Abrash’s thesis: Seeing is believing. ”What we just learned is an experience is real to the extent it convinces the perceptual system in your brain,” he said.

Ultimately, Facebook hopes to incorporate virtual reality to create a more immersive social network, one where users are basically able to relive moments from their friends’ lives.