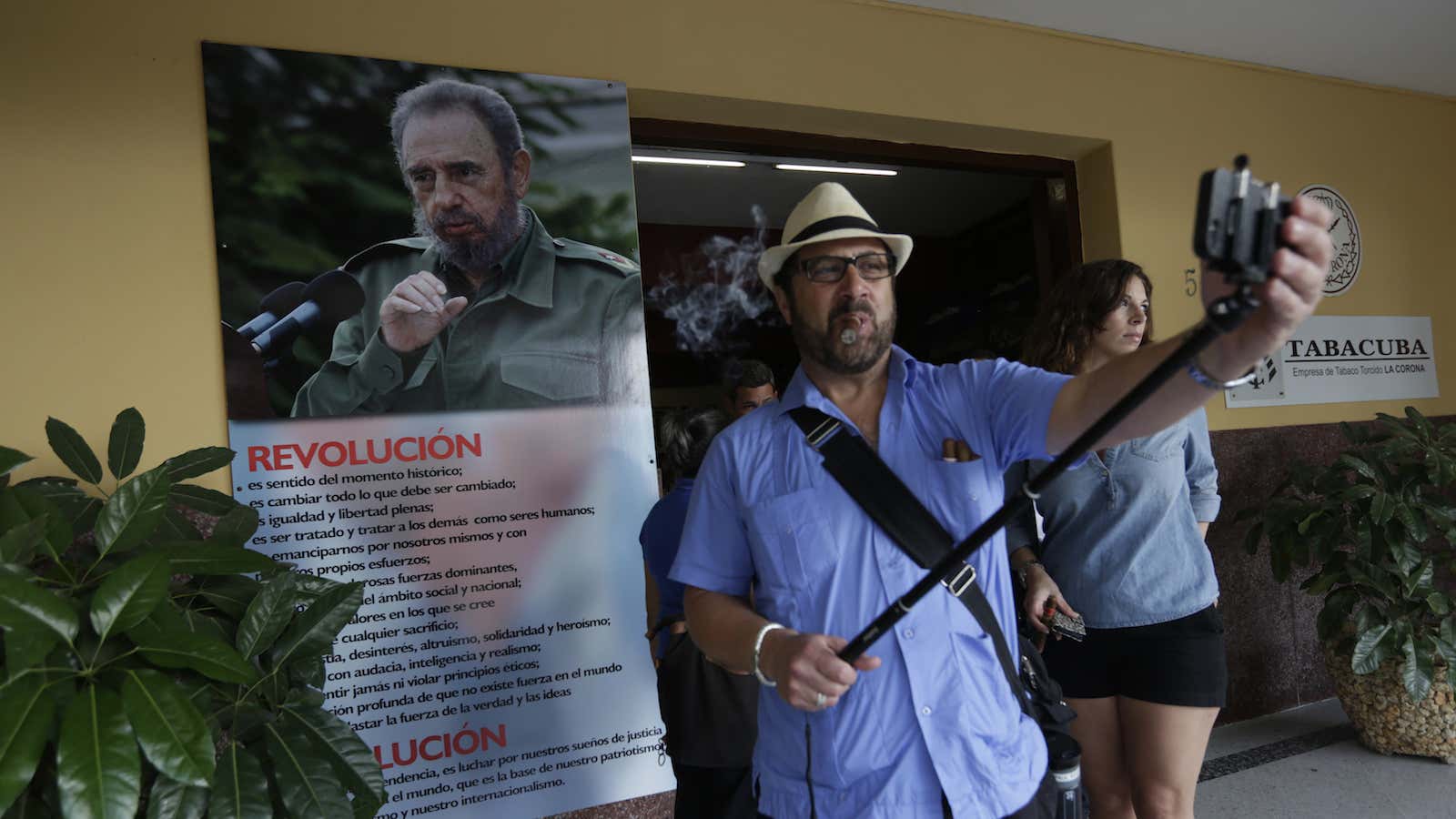

American television handyman Bob Vila is now in Cuba, so the island nation must be opening up, right? Since last December’s historic announcement that the US and Cuba would re-establish diplomatic relations, there has been a flurry of public speculation among US media on what the changes will mean for tourism, immigration, business, and baseball.

Much of this has been predicated on the idea that the country is “opening up,” or that the Obama administration has somehow pried open the iron cabana under which many Americans seem to believe that Cuba exists. A quick Google search on “Cuba” and “open” reveals headlines like these:

“Cuba opens up more to U.S. travelers, trade”—Associated Press

“How will Obama’s decision to open Cuba affect travel?”—Fox News

“Why Republicans should thank Obama for opening up Cuba”—PBS.org

Shortly after the news broke, the Daily Beast’s Michael Moynihan pointed out widespread eagerness among journalists and other public figures in the US to visit Cuba “before McDonald’s moves in.” Twitter saw plenty of speculation about the possibility of Starbucks, Walmart, and other US commercial corporations setting up shop in Cuba over the coming months.

Laying aside the fact that the new legal terms remain largely unresolved, it is curious that so many people see this as an “opening.” As a person who has spent long periods of time studying culture and technology in Cuba, I can’t accept the idea that the country was ever “closed” in the way that so many US media outlets seem to imagine.

Cuba has a local population of 11 million citizens, but an additional two million Cuban-born citizens live abroad, mainly in the United States, Spain, Mexico and Germany. Despite some bureaucratic hurdles to obtaining a passport, Cubans with the means to do so may travel internationally.

Internet access is limited but plenty of media is in circulation there, thanks to a robust local cultural sector, a steady flow of visitors from outside the country, and the use of mobile phones and pen drives to store and exchange music, videos, and other media. Tourists come from around the world to walk the beaches, hear the music, and yes, to marvel at the mix of people, color, tropical flora and architectural decay of Havana’s streets.

It’s true that to date, only a tiny fraction of the estimated 2 to 3 million tourists who visit each year have come from the US. But this is not Cuba’s doing—US citizens are as welcome there as anyone else. Until recently, unless they were visiting family members, US citizens were all but forbidden from traveling to Cuba. (Exceptions being a select group of journalists, academics, and religious and humanitarian aid workers—I’ve been through this process a few times, and it isn’t easy.)

So when it comes to US-Cuba freedom of movement, if any country is “closed,” it is the US.

At the same time, Cuban society is still significantly restricted in terms of speech, association, privacy, and economic rights. All major media in Cuba is produced by state-owned institutions. While there are independent websites run by Cubans, the dearth of Internet access makes these relatively oblique in the face of mass-produced state newspapers and radio broadcasts.

Regulations and omnipresent surveillance make large public gatherings or demonstrations a difficult (though not impossible) feat. And the vast majority of organizations large and small—ranging from street shops to farms to universities—are owned and run by the state.

So those prospective travelers already waxing nostalgic for a Cuba unspoiled by contemporary globalization should calm their nerves. Although we can expect some shifts in trade and commercial relations between the two countries, it is clear that the US is moving slowly on this front. There is also no clear sign of reform in Cuba’s economic regulatory environment for foreign enterprise. In fact, under Cuban law, any foreign company that wishes to do business on the island must enter a subsidiary agreement, under which the Cuban government owns a minimum of 51% of that company’s holdings in Cuba.

In short, it is impossible for foreign companies to actually own their own businesses there. Spanish companies such as the Meliá hotel chain have launched brick and mortar businesses on the island with some success over the last ten years, but they are presumably doing this under these terms. Anyone who fears that the country will fall prey to US companies is overestimating the power of foreign industry.

Like any other country, Cuba is not a monolith—there is a diverse range of interests and priorities among the government and the people, to which the current political system does not offer due voice. This new chapter in US-Cuba relations will generate greater economic opportunities for Cubans, if not more Starbucks franchises, as visitors from the US will unquestionably bring greater flows of capital into the country.

But there is no indication that this will open up new avenues for Cuban citizens to participate in or have meaningful impact on their country’s political processes. Just like anywhere else, this kind of change is not something that can be brought about by another government, or a company, or a civil society group from abroad. It will have to be the work of Cubans themselves.