- It came out of tragedy. In April 1996, a disturbed 28-year-old man named Martin Bryant killed 35 people with a semi-automatic rifle in the Tasmanian town of Port Arthur.

- It moved public opinion. In the wake of the shooting, “a national upwelling of grief and revulsion saw pollsters reporting 90–95% public approval for stringent new gun laws.”

- A conservative politician took the lead. Australia’s conservative Prime Minister John Howard spearheaded a push by Australian states and territories to severely restrict gun ownership that year, in what came to be known as the National Firearms Agreement.

- It targeted the kinds of guns used in massacres. “As the Port Arthur gunman and several other mass killers had used semi-automatic weapons, the new gun laws banned rapid-fire long guns, specifically to reduce their availability for mass shootings.”

- It encouraged people to turn in guns. The government “bought back more than 650,000 of these weapons from existing owners, and tightened requirements for licensing, registration, and safe storage of firearms.”

- It wasn’t free. “Total public expenditures were about A$320 million (US$230 million), or approximately A$500 per gun, which isn’t much less than what it costs to buy one.”

- But it was paid for. ”The buyback program was financed by an additional 0.2% levy on national health insurance.”

- It wasn’t voluntary. Long-barreled semi-automatic guns were outlawed. People were able to turn them in to authorities and be compensated without fear of prosecution. “The buyback was compulsory in the sense that retaining possession of the firearms was illegal, and the guns could not be easily replaced with similar firearms.”

- It resulted in a lot of guns. “The buyback is estimated to have reduced the number of guns in private hands by 20%, and, by some estimates, almost halved the number of gun-owning households.”

- That would be even more in the US. “In U.S. terms that would be equivalent to the removal of 40 million firearms.”

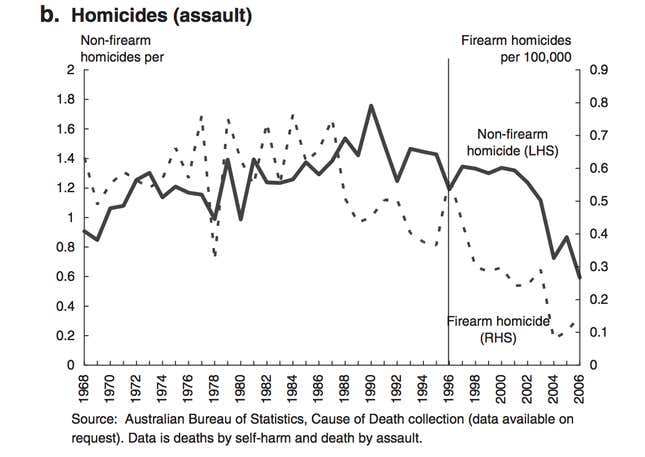

- Gun homicide rates fell. “In the 7 years before the NFA, the average annual firearm homicide rate per 100 000 was 0.43 (range:0.27–0.60), whereas for the 7 years after NFA, the average annual firearm homicide rate was 0.25 (range: 0.16–0.33).”

- Mass shootings stopped. “In the 18 years up to and including 1996, the year of the massacre at Port Arthur, Australia experienced 13 mass shootings. In these events alone, 112 people were shot dead and at least another 52 wounded (table 1). In the 10.5 years since Port Arthur and the revised gun laws, no mass shootings have occurred in Australia.” [Mass shooting defined as five or more dead. None have occurred since the publication of the paper in 2006, either. -eds.]

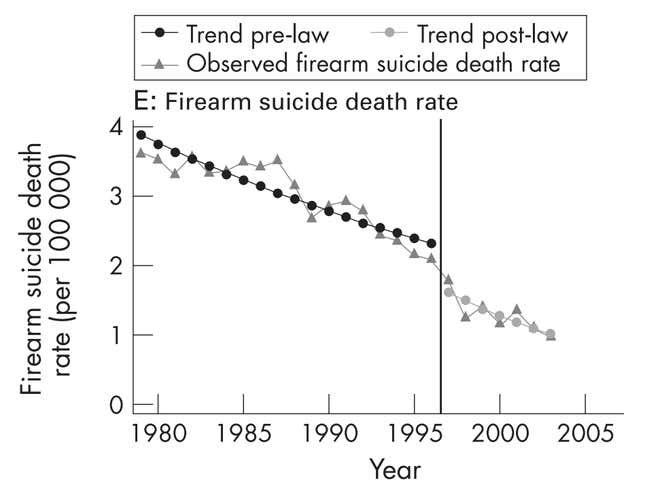

- Gun suicides declined. “In the 18 years (1979–96) [before the law], there were 8850 firearm suicides (annual average 491.7). In the 7 years for which reliable data are available after the announcement of the new gun laws, there were 1726 firearm suicides, an annual average of 246.6.”

- Some estimate that the buyback has prevented 200 deaths a year. “A firearm withdrawal equivalent to Australia’s buyback, using quite conservative point estimates, our estimates suggest that over 200 firearm deaths per year—mostly suicides—would be averted in a population roughly the size of Australia’s.”

- It probably won’t work in the US. “Three reasons why gun buybacks in the United States have apparently been ineffective: (a) the buybacks are relatively small in scale (b) guns are surrendered voluntarily, and so are not like the ones used in crime; and (c) replacement guns are easy to obtain. These factors did not apply to the Australian buyback, which was large, compulsory, and the guns on this island nation could not easily be replaced.”