On a sunny January afternoon, the heaviest things in six-year-old Miriam Foster’s backpack were her lunch box and her jacket, making it manageable for the kindergartener’s walk home.

“She does it herself from here to home, and home to here,” said Miriam’s mom, Tawankon Foster, 31.

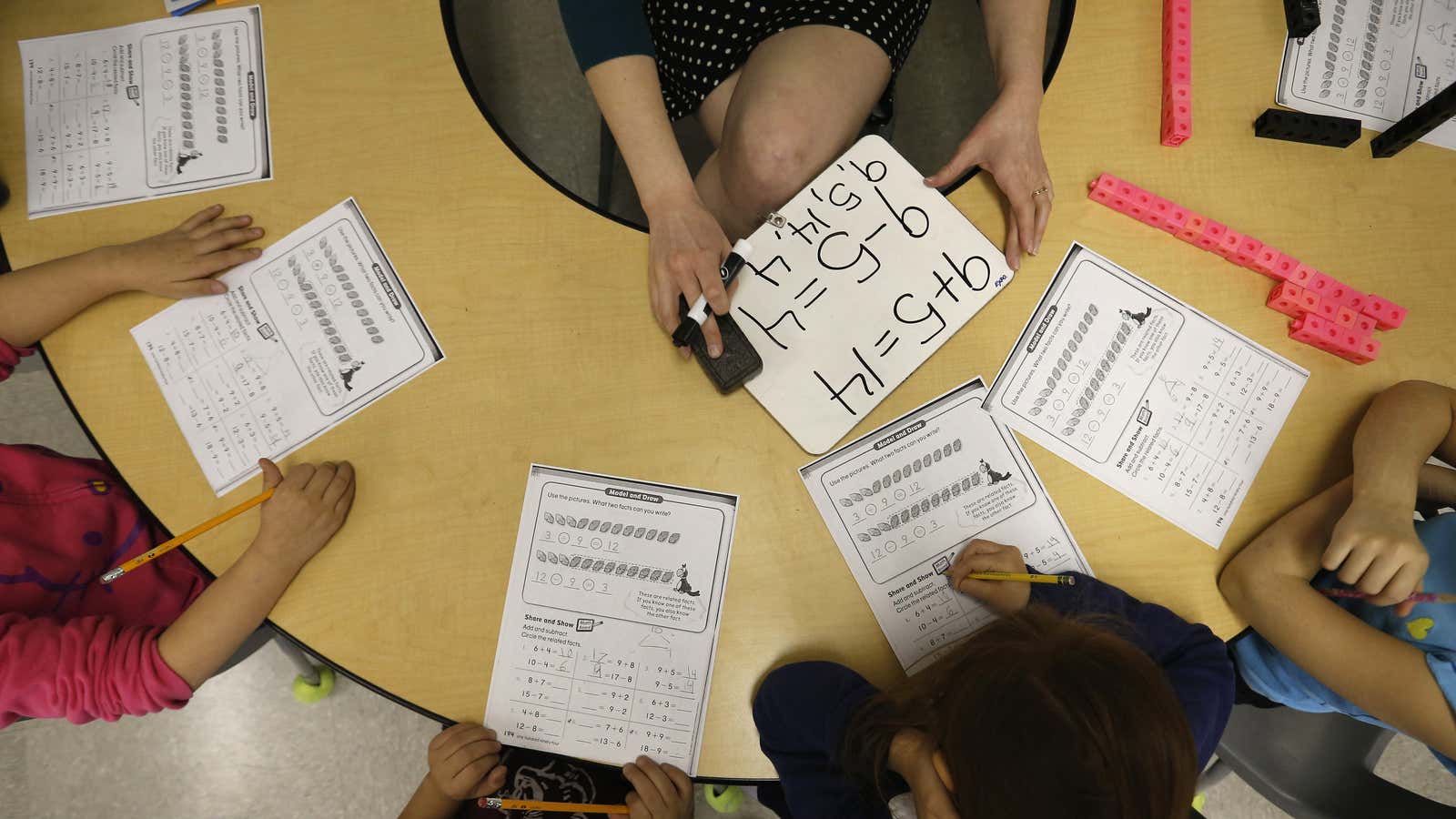

Her light load was not unique. At Emerson Elementary School in Berkeley, California, the occasional library book provides some heft, but the 20-lb. pack is a thing of the past.

After adopting the new Common Core standards, Berkeley has become one of an increasing number of districts across the country to reject textbooks or workbooks—at least for some classes. The new Common Core standards for kindergarten through 12th grade were widely expected to be a boon to textbook publishers, making it easier to market the same books in the 40-plus states that have fully adopted them. Instead, the standards may be rushing what many now see as the inevitable disappearance of the textbook.

In Berkeley, officials went looking for the best new math curriculum for the new standards. “We were skeptical that traditional publishers in 2013 would have been able to completely revamp their textbook and base it on the Common Core,” said Lori MacDonald, the Berkeley School District elementary math coach. (The standards were published in 2010.) “We looked at them and we got samples. It was not so different than what they had the year before.”

What the district chose instead of a traditional textbook was a curriculum that was available free of charge on the internet for anyone able to print it all out.

Across the bottom of the sheets of homework that Miriam also had in her backpack that night were the words “EngageNY”—a website set up by the New York State Department of Education that provides Common Core curriculum, designed mostly by nonprofit organizations with little or no experience in curriculum design.

A moment of disruption for textbook publishing

In 2014, sales of textbooks and other educational materials (not including technology purchases) for the kindergarten-through-12th-grade market were 3% lower than in 2009 according to a survey of seven education publishers, including the biggest three, by the Association of American Publishers.

Part of the sales weakness is the politics surrounding Common Core. Jay Diskey, executive director for association’s PreK-12 Learning Group, noted that textbook sales have picked up in the last two years as the recession ended, but attributed the lack of a Common Core bump to “political headwinds.”

Education leaders and experts said a key problem is quality. It takes time to write high-quality textbooks, and others have been more nimble than the old publishing giants, leaving an opening for the freely available New York curriculum designed by new players to become a major force in the industry.

“There are places that want to purchase but they’re just holding off because they’re waiting for a better [textbook] series that more completely covers the standards,” said William Schmidt, co-director of the Education Policy Center at Michigan State University, who has reviewed upwards of 600 math textbooks to evaluate them for alignment to the new standards. “I’ve actually advised districts most recently that they should wait for something that’s better, instead of spending money on something that’s not quite yet there,” he added.

In many places, teachers are putting their own curriculum together or schools and districts are doing the work. The lack of a definitive high-quality math textbook created a moment for the newcomers to attract followers from around the country.

“We’re going from the dominant paradigm of the publishing industry to a much more nimble, often electronically distributed, more Silicon Valley-like lifting up of content from lots of sources, often from teachers themselves for other teachers and leaders, with new distribution platforms that go directly to users with a much broader base of content developers,” said Scott Hartl, CEO of New York City-based Expeditionary Learning, which developed an English curriculum for EngageNY. “The industry itself is changing.”

Two studies of math textbooks last year, by Schmidt and another professor, have found major publishers’ math textbooks labeled Common Core that don’t actually address key parts of the new standards and include extraneous material while remaining similar to past versions of the textbook series.

One curriculum that did stand up well was the set of online math lessons developed for the New York Department of Education.

“Our own analysis did show [EngageNY] to be quite consistent with the Common Core standards,” Schmidt said. Similarly, a high-profile review of Common Core math curriculum materials—released this month by EdReports.org, which touts itself as a new textbook Consumer Reports—gave top marks to the EngageNY math program, which goes by the name Eureka Math, and to none of the big publishers’ textbook series.

New York State’s alternative to the textbook

To preempt the criticism that New York State was leaving teachers stranded with no guidance as officials rolled out the Common Core standards, the state spent $28 million of its federal Race to the Top grant to develop the curriculum for math and English that schools could use as part of the transition. Major textbook publishers were not interested in making their work available for free, so the nonprofits Expeditionary Learning, Core Knowledge and Great Minds, as well as the for-profit company, Public Consulting Group, filled the void.

“We were really clear that the Common Core was asking students to think, to make meaning, to draw conclusions, to problem-solve, and we were quite convinced, and we still are, that there was nothing commercially available or freely available that met the standards,” said Kate Gerson, senior fellow at New York’s Regents Research Fund, the privately funded group that works with the state Education Department.

After the EngageNY curriculum materials were published in 2013, calls for help with the materials began flowing in from all across the country. Because the curriculum materials are available for free online, the exact number of schools using them is difficult to come by, state officials said. But EngageNY lessons appear to represent a small but rapidly growing part of the materials being used in classrooms across the country. The New York site has seen 19.5 million downloads since 2011, though that number also includes professional development materials.

“It’s been the experience of our team that we hear from folks all over the country,” said Gerson. “They’re finding it useful, and they have questions about it and they’re wondering exactly how to get it right. We’re excited about that; we’re excited that it’s been useful to people.”

More than 250,000 students in 30 states are using materials of Core Knowledge, the nonprofit that developed the early elementary school English curriculum for EngageNY, according to a company called Amplify, which is working with Core Knowledge. And there have been more than two million downloads of Expeditionary Learning’s units from the EngageNY site as well as their own site, according to the nonprofit. The curriculum is being used in at least 447 districts in 36 states as well as Washington, DC.

Louisiana published a review of Common Core curricula last year, and gave EngageNY’s Eureka Math a top ranking, leading a large number of districts in the state to adopt it, according to officials with the nonprofit Great Minds Inc., which developed Eureka Math for EngageNY. Parts of Core Knowledge also ranked at the top along with one textbook series.

Favorable reviews there and elsewhere of the free EngageNY materials have helped expand interest. Achieve, a nonprofit group that backs the Common Core standards, gave three Expeditionary Learning units its highest ranking.

“Do we want as many districts as possible adopting our stuff? Sure. Am I more interested in our setting a new standard for the quality of instructional materials in reading and math? Yes,” said Great Minds executive director Lynne Munson. “I’m vastly more interested in seeing that more students are learning these subjects well than in selling anything to anyone.”

She added that she has to assume textbook publishers are taking note. “I’m assuming that if there are textbook publishers that are noticing that a new curriculum is out there and winning adoption and significant rankings and accolades they would study that curriculum and appreciate those characteristics and perhaps choose to emulate those.”

Textbook industry officials said the criticisms of their materials’ quality are overblown, that the work of developing materials takes time and that other states including California have approved for use plenty of traditional textbooks as part of adopting Common Core.

“What I see are educational publishers working very hard to get this right—to design instructional materials that are aligned with the Common Core,” said Diskey, of the Association of American Publishers. He noted that the Common Core is not a curriculum but the funders and architects of it have begun to support entities that “are designing guidelines, rubrics, and curriculum review processes. It seems that they have arrived at the doorstep of Common Core curriculum development and selection.”

EngageNY’s Eureka Math has been the butt of a criticism, too, for uneven quality, for presenting too much material to be covered in a single year and for making it impossible for parents to help their own children do their homework, resulting in some districts that had adopted the curriculum electing to abandon it. New York State officials as well as the publisher defended the quality of the materials. State officials said that, the math curriculum may require some condensing, particularly since many students’ skills are not officially up to grade level, adding that they have provided trainings to teachers to be able to address that. And Eureka Math officials note they have a guide for parents available on their website.

In English Language Arts, EngageNY’s lessons that provide a script for teachers have drawn fire for leaving no leeway to teachers, according to critics. State officials said they never intended to require teachers to read by rote the words on the page, only to provide as much guidance as possible.

Online materials still require paper

School districts are discovering that materials available for free download can still cost money. In Berkeley, MacDonald, the math coach, says she spent half her time last school year preparing downloaded documents for printing. Most elementary school students go home with a photocopied sheet of homework each night—though turning trees into math homework didn’t make every parent happy. It is Berkeley, after all.

“That’s not the best, because we have so much paper,” said Maryse Bill, 45, mother of three children in the Berkeley schools, noting otherwise she’s happy with the new math, which reminds her of the curriculum from her own grade school in Switzerland.

A future without textbooks was, indeed, supposed to look sleeker with computers, laptops, tablets, and smartphones providing the lessons. It may yet—and it does in some places already. States across the country have passed requirements to move toward digital instruction. At Emerson Elementary School, in Berkeley, classes have access to laptops though classes still take turns using the school’s internet.

Meanwhile, inside an old brick school building the district set up a copy center. Beginning as early as 4a.m., and sometimes seven days a week, the copiers are churning out the materials that have replaced traditional workbooks or textbooks. The copy center is run by Emil Brown, who sometimes pulls a seven-day week to print out online curriculum for the district’s schools.

Xerox, which has a contract for Berkeley’s curriculum, has prepared for a digital future, he notes, but for now they’re still making money on their old-school business.

“We practice and preach digitizing and technology,” he said. “But at the end of the day, students still need tangible items.”

Textbooks remain a powerful force

Not all schools have abandoned traditional textbooks yet. New York City schools spent more than $50 million last school year on English and math textbooks for kindergarten through eighth grade, the vast majority for purchases from traditional publishers, according to figures provided by the New York City Department of Education. New York City elementary schools spent nearly $11 million on Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s GO Math!, and middle schools spent nearly $12 million on Pearson’s Connected Math, which EdReports.org found to be partly aligned and not aligned, respectively, to the standards. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt spokeswoman Jennifer Berlin noted the EdReports.org was “just one of many organizations that review instructional materials” and that GO Math! “is a widely used and respected program that has repeatedly been found to be rigorous and aligned to the Common Core.”

Low-performing schools in New York City were the ones more likely to buy the standard math textbooks on offer, while the majority of the top-performing schools passed, according to Hechinger Report analysis based on a list of schools that opted out of the city’s endorsed list of Common Core textbooks.

“There is a lot of urgency in these low-performing schools. They don’t have the luxury to wait around and see” if something better comes along, said Morgan Polikoff, an education professor at University of Southern California professor. He noted that the gap in buying patterns “could compound the inequality” between low- and high-performing schools when the textbooks that guide instruction aren’t up to the new standards.

New York City Department of Education spokeswoman Devora Kaye said the agency “is committed to having high-quality instructional practices and materials in all our classrooms” and is “constantly evaluating and soliciting school communities’ feedback on the materials we choose.”

Core Knowledge, one of the nonprofits that provided curriculum for the New York site, has also partnered with the for-profit company, Amplify, to create a textbook version for sale—in part because the skills-based portion of the curriculum is printing-intensive. For districts to buy the whole curriculum, it’s cheaper than printing it out, they say, because of the volume discount. (The reading portion can be printed economically from the company’s website or the state’s, they noted.)

Amplify, a News Corp subsidiary, is better known as a technology firm, but its spokesman, Justin Hamilton, stuck up for the textbook—at least for the early grades—over screen time.

“We think in these early grades there’s big benefits to still working with print materials,” said Hamilton.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.