An effort to weaken organized labor is sweeping the Midwest, a region with a rich history of union activism.

The strategy takes advantage of a curious provision of US labor law, section 14 (b). It allows states to pass laws that prohibit unions from negotiating the collection of union dues with employers, and more specifically, from compelling workers covered by the bargaining agreement to pay the unions as a condition of employment.

Under labor law, employees that do not pay dues enjoy the same wages, benefits, and protections as those who do. A labor union that discriminates against someone covered by the contract (and who doesn’t pay dues) is liable to a “duty of fair representation” lawsuit.

Corporations call these laws “right-to-work” (RTW). Unions prefer the term “right-to-freeload” (RTF).

Last month, Wisconsin became the latest (and 25th) state to pass legislation that allows union-covered workers to refrain from paying dues. Legislators in Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, and New Mexico are agitating to following suit.

What do these laws mean for organized labor?

What the right-to-work movement is not about

First, let us begin by anticipating and then dismissing several pretexts.

First, RTW is not about granting workers the freedom to associate, as supporters argue. If that were the case, then RTW advocates would approach the minority union concept, keenly argued by Charles Morris in The Blue Eagle at Work: Reclaiming Democratic Rights in the American Workplace, with equal zeal.

Morris explains that the intent of the original labor law was to promote collective bargaining by compelling employers to negotiate with groups of workers on behalf of members only, even if they did not constitute at least 50% of employees. Silence on this issue from right-to-work supporters undermines the credibility of the “freedom to associate” motive.

RTW is also not about making labor unions more responsive to workers by allowing them to withhold dues payments. The very same objective could be achieved by allowing union objectors to remit the equivalent of union dues to an agreed-upon charity, enabling workers to register dissatisfaction with a union without giving them a financial incentive to do so. Hence, the objection would genuinely reflect ideology or religious concerns, and not free-rider opportunism.

However, the American Legislative Council (ALEC)-sponsored legislation sweeping the nation expressly prohibits any requirement to “pay to any charity or other third party, in lieu of such payments, any amount equivalent to or a pro-rata portion of dues, fees, assessments, or other charges regularly required of members of a labor organization.”

ALEC is a group of conservative state legislators that crafts “model” legislation and lobbies like-minded politicians to pass the bills, as has been the case with right-to-work.

What the right-to-work movement is about

One way to understand the real intent of RTW is to imagine what would happen to the public services in one’s town, city, or state if the payment of taxes were voluntary. How long would our public schools, libraries, sanitation systems, water facilities, parks and so forth function if taxes were optional?

Charging fees would be impermissible, because persons that refuse to pay tax would have an equal right to the schools, libraries, garbage collection, water, etc, as those that do pay. Just like RTW, the services would have to remain equally accessible to tax payers as well as tax deadbeats. Public services as we know them would collapse.

All collective endeavors require resources to achieve their goals. Labor unions represent working persons at their place of employment through collective bargaining. Organized labor also has an admirable history of fighting on behalf of non-union workers through political advocacy on issues such as workplace safety, minimum wage and public health insurance. The obvious intent of the ALEC-funded RTW effort is to burden the union movement’s pursuit of these goals by making it difficult to acquire financial resources.

Labor’s “free riders” are increasing

Evidence of a RTW burden is beginning to appear in state-level statistics.

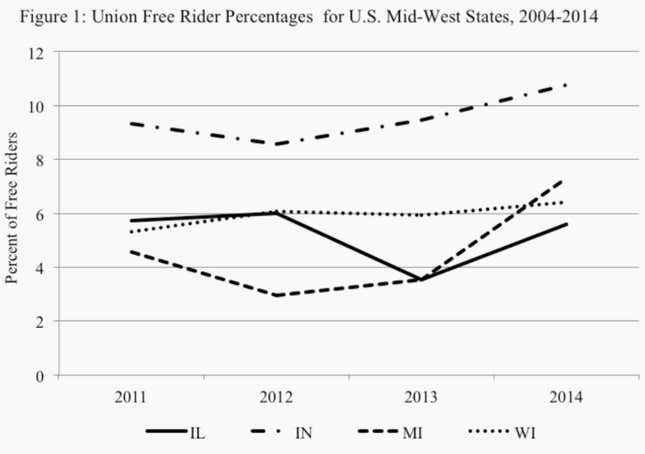

The graph below provides trends lines for the percentages of non-union “free riders” in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin. The free rider percentage is the percent of persons in the state that are covered by a collective bargaining agreement but are not union members.

The estimates are from the Current Population Survey administered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

The top line is Indiana, which passed RTW in 2012. The dashed line at the bottom is Michigan, which passed RTW in late 2012, effective 2013. Both states show a gain in the percentages of free riders following the passage of RTW laws.

The growth in free riders for Michigan would have been even more dramatic had RTW applied immediately to all collective bargaining agreements. Prior to the law, many unions across the state signed binding letters of intent with their employers to extend union security provisions. As these letters expire, the RTW burden will predictably increase.

Wisconsin (dotted line) displays an upward trend in free ridership, although quite gradual by comparison with Indiana and Michigan. The trend in Wisconsin might be attributable to the evisceration of collective bargaining rights for public employees in 2011. The Midwest state that has experienced little change in bargaining law, Illinois (solid line), has a free rider rate from 4% to 6%, and no discernible trend over the period.

Right-to-workers are undermining the working class

It is important to not only acknowledge these trends but to understand the context that gives rise to RTW, or any other anti-worker policy. What does RTW symbolize?

On a political level, the expansion of RTW is symptomatic of the resurgent influence of corporate control over political affairs. Advocates for RTW, as agents of the corporate class, evidently have enough resources to convince persons to vote to undermine one of the few social institutions that advance the interests of working persons.

Observing these events brings to mind the quip attributed to the 19th-century railroad baron, Jay Gould, during an earlier era of great inequality: “I can hire one half of the working class to kill the other half.” Elite arrogance is back in vogue.