Starting the second half of the year, the biggest game on Earth—if you happen to be an oil company—will be Iran.

In the coming weeks, leading countries known as P5+1 will resume negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program. The aim will be to flesh out their April 2 preliminary agreement and sign a final version on or about June 30. Next, Iran is eager to get started vastly increasing its sanctions-stunted oil production. The result a few years down the road will be yet another oil gusher to add to the US shale oil boom, and thus another challenge to OPEC and Russia.

Assuming a final nuclear accord is concluded, Iranian oil probably wouldn’t flood the market for awhile, experts say. First, Tehran will have to comply with restrictions on its nuclear program, and then get its actions verified by international inspectors.

But once those steps are complete, Iran will quickly look to sell off approximately 35 million barrels of surplus, stored oil for which it has apparently not managed to find buyers. Analysts don’t seem to make much of this ready inventory, but if Tehran sells it in 500,000-barrel-a-day increments—a reasonable pace—it could send an already-saturated market back into a price nosedive for more than two months.

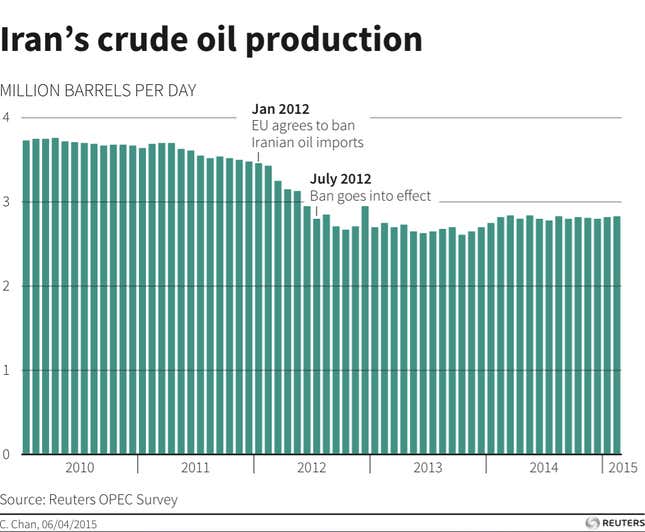

But that isn’t all. After that, Iran will push production back up at currently producing fields. Until the sanctions hit in 2012, Iran produced 3.6 million barrels of oil a day, of which it exported about 2.5 million. Today, it produces much less—about 2.8 million barrels a day—and exports just 1.1 million.

Most experts think it’s reasonable to anticipate a return to 3.6 million barrels a day in Iran’s first year or so back on the market. This would add 800,000 barrels to the global supply—assuming production from elsewhere holds approximately where it is now, and other OPEC members such as Saudi Arabia do not reduce their output to accommodate Iran—which would more or less lock in relatively low global prices.

In terms of the global oil glut, it won’t matter if, as some analysts forecast, US shale oil production declines; Iran’s oil would replace it on the market.

Then will come the oil deals

By then, the world’s big oil companies presumably will be deep in negotiations with Iran. Their objective will be the fourth-largest petroleum reserves on the planet—an estimated 157 billion barrels of oil. Tantalizingly, some 40% of the country’s known resources have yet to be developed (paywall). China could be a big player in future development.

The unknown is what terms Tehran is prepared to offer, though it has had years to contemplate this. It’s presumed that the government won’t provide the standard leased structure preferred by companies—a contract that’s the most popular way to list discovered reserves on a balance sheet. The reason is nationalist sensitivities—virtually no OPEC member would voluntarily allow a hint of a return to the old days when big Western oil companies called the shots in the region, dictating the terms of the oil deals and sometimes the politics.

In recent months, the oil sector landscape has changed considerably, both literally and figuratively, not only with low prices but with attractive fields on offer in Iraq, Mexico, and Angola, not to mention US fields such as shale and the Gulf of Mexico.

But if the past is a teacher, the scent of conventional, relatively cheap-to-develop, onshore fields—again, given the right terms—will create a stampede.