India woke up this week to the shocking news of a girl who was gang raped on a private bus in South Delhi. The victim and her friend are still in critical condition. Police have arrested four people accused of the crime, while two are absconding.

Sunday’s case prompted Sushma Swaraj, the leader of the opposition in Parliament to ask for capital punishment for rapists. The Prime Minister called the crime “heinous” and “very upsetting.” On Facebook and Twitter, people signed petitions and argued about the advantages and disadvantages of terming Delhi the “rape capital” of the country.

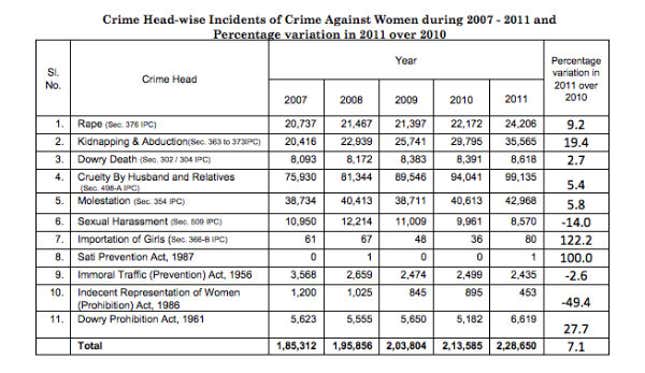

While this has led to the usual outrage on news and social media, historically, very little has been done to ensure the safety of Indian women. However, one change has come: how Indian women themselves define rape. Data released by the National Crime Records Bureau indicates a 14% drop in the number of cases of sexual harassment in 2011. Rape, on the other hand, has risen by 9.2%, with a recorded 24,206 cases in India in 2011.

“With an unsympathetic police force and the lack of support from family members, women tended to keep quiet about rapes. And if they felt forced to complain, mostly because of the threat that it might happen again, they preferred to crouch it under the sexual harassment tag,” says Nivedika Menon, a women’s right activist in Delhi.

In fact, sexual harassment itself is a relatively new term in India. Even today, most incidents of harassment are reported as “eve teasing,” which does not convey the severity of the crime or carry a harsh enough punishment. While eve teasing itself is not a term used in the Indian law, violators are booked under a section of the penal code that carries a maximum sentence of three months of imprisonment. But hardly anyone has gone to jail for eve teasing. Obscene gestures, indecent body language, acidic comments directed at a woman or girl carries a penalty of simple imprisonment of one year or a fine.

While it’s an improvement that more Indian women are coming forward to report rape, the police force is still apathetic. A sting operation conducted by an Indian magazine, Tehelka, revealed that many police officers thought the victims were to blame. “Only 1% of the cases are genuine,” says a police officer; while another says that most of the time girls get into strange cars voluntarily. When victims go to the police station to report rape, they are often jeered and mocked and actively discouraged from filing a report. If they do manage to file one, they step up to the next level of apathy, at the hands of medical officers.

Even until last year, AIIMS, the apex government hospital in Delhi, was not following standard operating guidelines for medical examination of rape victims or using standard kits for collection and storage of samples procured from the victim. Because of this haphazard collection and storage of crucial evidence, the cases often collapse in court and the perpetrators go scot free. In the last 29 years, conviction rates of rapists dropped from 37% to 26%, according to an editorial in the newspaper, The Hindu.

For regular Delhi girls, sexual harassment and the possibility of rape is an everyday fear. Monica Sharma, 25, works as a receptionist in a beauty salon in Gurgaon, a suburb of New Delhi. She leaves work at 7 p.m. and although her commute is only 6 kilometers, it takes her 40 minutes to get home. “I can’t even count the number of times strangers have come in a rickshaw and tried to pull me in,” she says. When she tells her family about it, her brother insists on picking her up but often he gets delayed at his workplace or gets stuck in traffic so that it isn’t a practical solution. Now she carries a sachet of chili powder in her bag to throw in the eyes of an assailant and “prays to God” everyday when she step out of work, she says. She has no faith in the police, in either preventing these crimes or dealing with the victim appropriately.

In a few days, like the cases before this one, chances are people will forget and move on to the next outrage. But even if government does nothing, India’s women have forced statistics to represent them for who they are—victims.