They “knew exactly what they were looking for,” said 56-year-old Briton Tony Tancock in an interview with The Telegraph. Thieves had recently swiped six of his most cherished treasures. No, not paintings. Nor was Tancock talking about lost jewels, fine Persian carpets, Flemish tapestries, or a set of Wedgwood china dishes.

Tancock’s world revolves around Cavia porcellius, the guinea pig, which he breeds at his home in Devon, England. But Tancock’s guinea pigs are no ordinary, pet-store variety. These are winners— frequently best-in-show. Which is why, when a half-dozen of his best pigs went missing in early Apr. 2015, he suspected a rival breeder.

The Devon pig-napping has launched a regional police hunt. “They took two tortoiseshells, two black and two brown,” Tancock told The Telegraph. “[They were] all short-haired guinea pigs that besides being show quality, were also beloved family pets … They left six which were not show quality, plus two other show ones.”

The Telegraph also spoke to Kathy Dudding, of Britain’s National Cavy Club (cavy being an alternative name for guinea pig). “It has happened before, because they want the best,” she explained. “It has even happened at shows, when guinea pigs have been ‘borrowed’ out of the cages. The owner comes to take their animal home and it has gone.” Rivals will “have your throat,” Dudding said. “The idea is to go and have a good day out and remember it is supposed to be a hobby, but a large amount of people don’t treat it that way. They take it too seriously.”

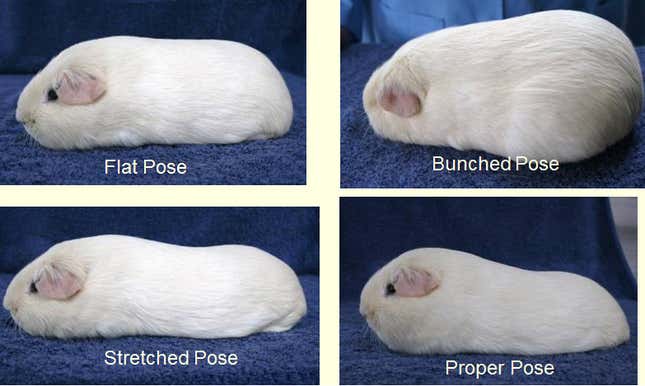

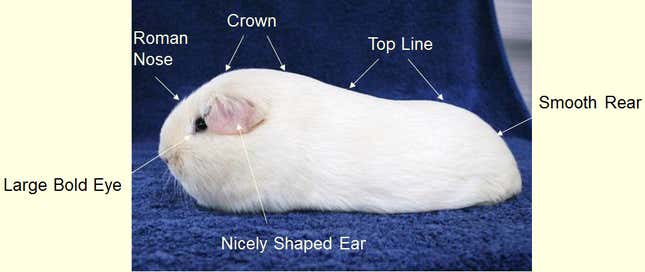

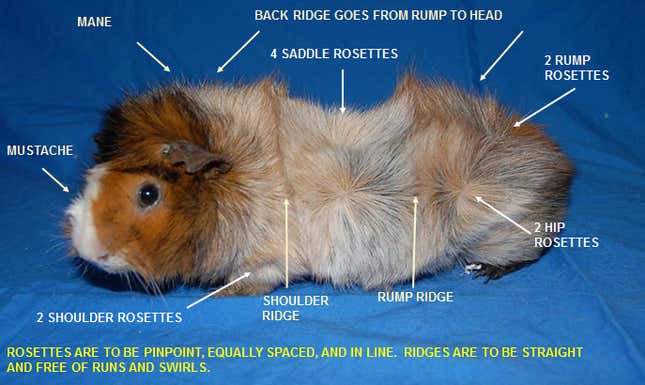

The shows themselves are intense affairs, though. Given the stringent rules for everything from coloration to pose (yes, pose), it’s not especially difficult to understand why some breeders might get caught up in the thrill and intrigue of guinea pig pageantry.

“A legion of ‘keyboard warriors’ even post abusive comments about other breeders’ animals on Facebook,” The Telegraph reports.

Bryan Mayoh, president of the British Cavy Council, disagrees with Tancock and Dudding’s hypotheses, however. Mayoh surmises that while the likeliest culprit is indeed a fellow breeder, the motive probably had little to do with competitive envy. “I would suggest that a personal dispute is a far more likely explanation than that some person was envious of his cavies,” he told The Daily Mirror. “’In 25 years of showing I never had a cavy stolen, nor have any of my fancier friends.” Mayoh also cites a kind of unspoken code between guinea pig fanciers: “Real fanciers know how important cavies are to other fanciers and would not dream of trying to steal animals from them.”

Guinea-pig fancying became popular in the British Isles—and around the Anglophone world—in the late 19th century. However the animals were first introduced to the Western world in 1500 by Spaniards, returning from explorations in South America. Even today, to the ordinary South American, the idea that such fuss could be kicked up over a few missing conejillos would no doubt be amusing. In Peru, Ecuador, and other Andean countries, the furry creatures are more often lunch or dinner than pet or show specimen.