Senator Marco Rubio threw his hat into the presidential ring yesterday in front of a historic background: Miami’s Freedom Tower, the “Ellis Island of the South,” where Cuban refugees were processed after fleeing the Communist revolution.

Rubio is the son of some of those refugees, and his story of rising to political prominence from humble beginnings will be an asset as he seeks to guide his party into America’s multi-ethnic future. He cast his campaign as an effort to throw off the old tropes of the past, an apt message for someone challenging the scion of his own party’s biggest political dynasty, Jeb Bush, for the Republican nomination—and, should he win this, perhaps facing Hillary Clinton, a figure on the US political stage for more than two decades.

But there’s at least one area where it is Rubio who is stuck in the past: His fealty to the US embargo on Cuba.

At one time, this was a no-brainer for politicians, Republican or otherwise: The huge surge of Cuban refugees into Florida—and their vehement opposition to Fidel Castro’s regime—have made them a political force in one of the most populous US states, and therefore a major prize in a national election. They blunted the Democratic advantage among Hispanic voters, and blessed America’s hardline policy toward Cuba, rendering it untouchable for 50 years despite it having almost no effect on the island nation’s communist regime.

But in December, US president Barack Obama, with the freedom that comes with a lame-duck presidency and the opportunity created by Castro’s stepping down as Cuba’s leader, moved to normalize relations with the Cuban government. This entails re-opening the US embassy, allowing more travel and remittances, and taking steps toward ending the US trade embargo on the country and opening its markets to US business.

Rubio has condemned the policy, promised to “unravel” it, calling that Obama “not just naive, but willfully ignorant of the way the world truly works.”

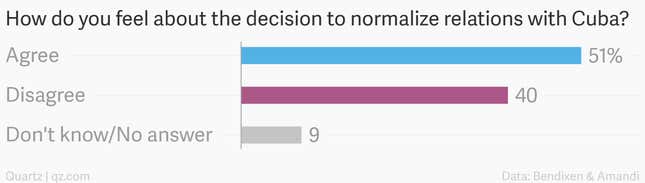

But do his fellow Cuban-Americans agree? Not according to a poll by Bendixen & Amandi, released last week at a conference on Cuban business opportunities. In mid-March, Cuban-Americans cautiously supported efforts to open up the relationship:

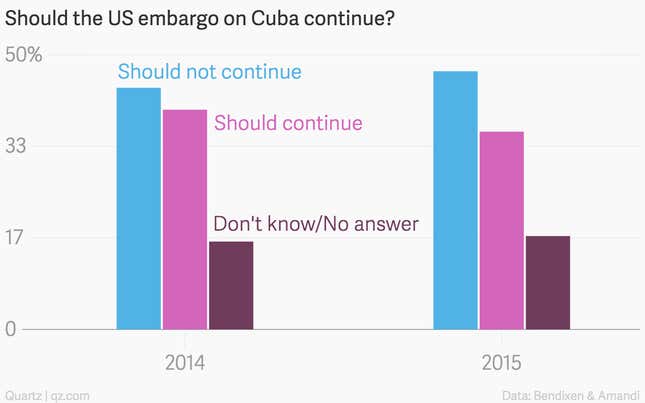

And the “agree” camp has been gathering momentum:

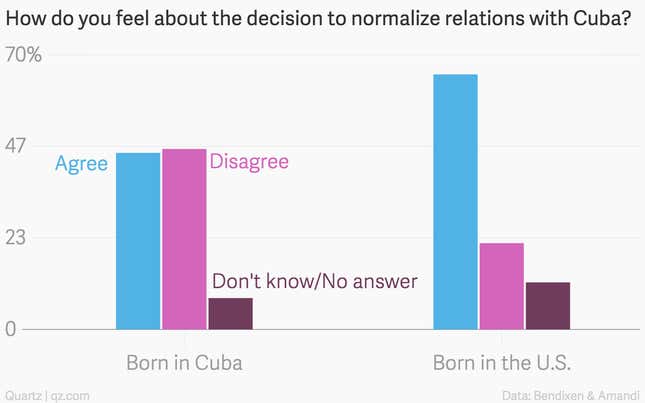

The reason why? Cuban-Americans born in the US just don’t support the embargo:

Drill down further, and you’ll find that even Cuban-born Americans tend to support relaxing the embargo on Cuba if they are part of the younger generation of immigrants. Some 62% of Cuban refugees who arrived in the US before 1980 disagree with Obama’s decision to normalize relations, but 56% of those who came after 1980 agree with the president. The numbers are even starker when you look only at age: Cuban Americans younger than 50, wherever they were born, generally support an end to the embargo.

Political scientists have tracked this trend in previous elections, finding an increasing number of Cuban Americans supporting the Democratic party, but those polls were taken without a Cuban American on the ballot, and Rubio may change that calculus. But it has been hard for the young senator to sync up with Hispanic voters: He championed immigration reform legislation—widely seen as part of an effort to establish his electoral bonafides with Hispanics, who registered broad support for the effort—only to ultimately changed his mind and vote against the bill when faced with conservative opposition.

Shifting the median views of an entire political party is no easy task, and stumbles are to be expected. But if you’re betting on Rubio to up-end his party’s establishment, remember that in some respects, he may be more old-school than new blood.