A clearer understanding of Alzheimer’s disease has been one of the the great unmet needs in health care and pharmaceutical research. Billions have been spent developing and testing therapies that have failed.

Now, a team led by doctors Matthew Kan and Jennifer Lee at Duke University are questioning a long-held assumption about a cause of the disease, and this week they released a study in the Journal of Neuroscience that points toward a a possible alternative way of thinking about it and treating it. Rather than the result of an immune system activation and overreaction, as current thinking about the causes of the disease suggests, the researchers unexpectedly found it might be the result of immune suppression.

Their study of genetically modified mice designed to model humans with Alzheimer’s found that a type of immune cell that protects the brain began behaving abnormally in affected areas, and was consuming a semi-essential amino acid (a building block for proteins) called arginine.

Blocking that process with a drug called difluoromethylornithine (or DFMO, which has been tested on human subjects as a cancer treatment) helped prevent the buildup of beta-amyloid, protein fragments that make up plaques long thought to be a major cause of Alzheimer’s, and memory loss.

The idea that arginine deprivation and local immune suppression might contribute to the disease—the previous assumption was that an inflammatory response and an overproduction of certain molecules were the primary culprit—is new and potentially fascinating. Alzheimer’s is so poorly understood that any potential advance is important.

But the results of the latest study shouldn’t be interpreted as a near-term step toward a cure. There are many caveats to consider—among them, animal models of Alzheimer’s rarely translate to people, and beta-amyloid plaques (if it is even the right thing to be targeting with treatment) have proven a tricky substance to reduce.

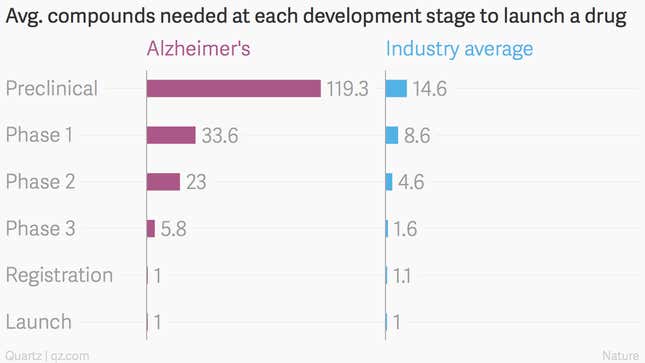

Indeed, drugs developed to treat Alzheimer’s fail at a much greater rate than other types of medicines. A full 99.5% of compounds intended to treat the disease have failed, and those that exist are minimally effective. The average attrition for drugs is a less bad 95.8% across all stages:

This latest study used a new type of genetically modified mouse that better models the human immune system, the authors write, but it’s tough to produce relevant results from mice for something as complicated as the human brain and memory. Some of the study’s findings are dependent on measuring mRNA molecules in mouse brains, which can be highly variable and tough to draw robust conclusions from.

Another reason for caution: the study is entirely dependent on the idea that amyloid plaque buildup (resistant to the drugs that have attempted to treat it thus far) is the reason for the disease’s cognitive effects. A recent study by researchers at the Mayo Clinic points to tau protein. Or it might be something else entirely.

In any case, once you have amyloid plaque buildup, the damage to the brain is already done. Research exploring alternate methods that could help identify risk and potential interventions far earlier might be more fruitful.