Over the centuries, women have gone to great, and even damaging, lengths to make themselves desirable according to the societal standards of the era. There is perhaps no better example of this than China’s female footbinders.

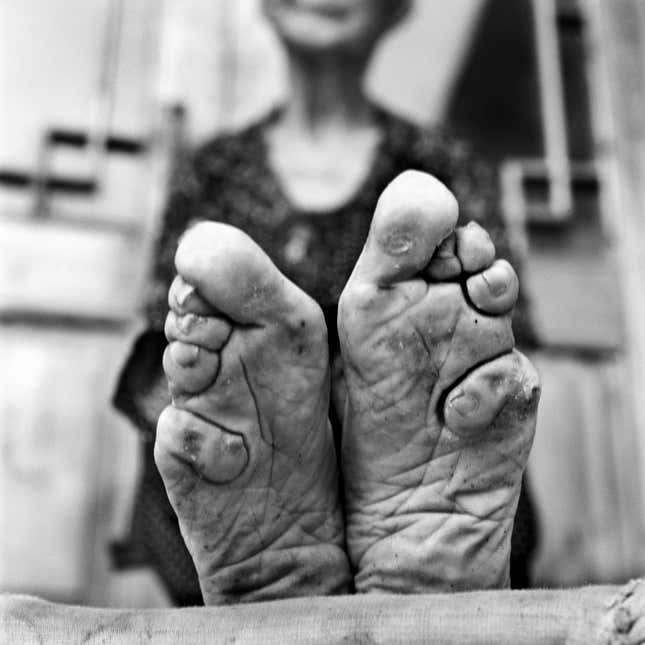

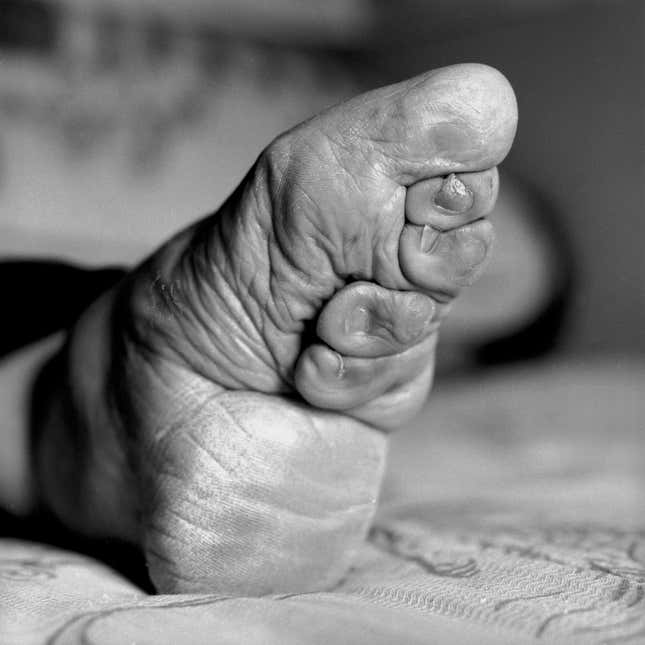

The origins of Chinese foot binding dates back to at least to the 13th century. The practice is not for the faint of heart: young girls’ toes and arches were methodically broken, sole and heel crushed together, toes smashed flat, then held in place with tightly-wrapped silk strips. After several years, the eventual result was a tiny, triangular shape: the crippling, fetishized ”golden lotus”.

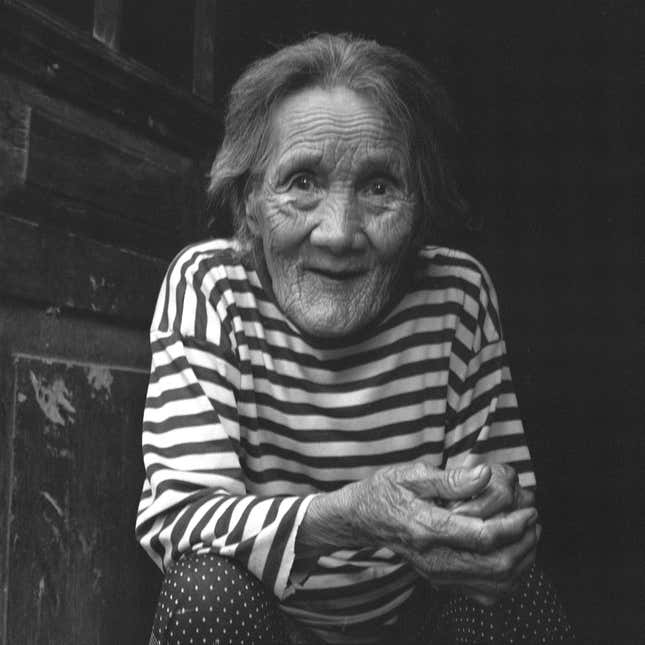

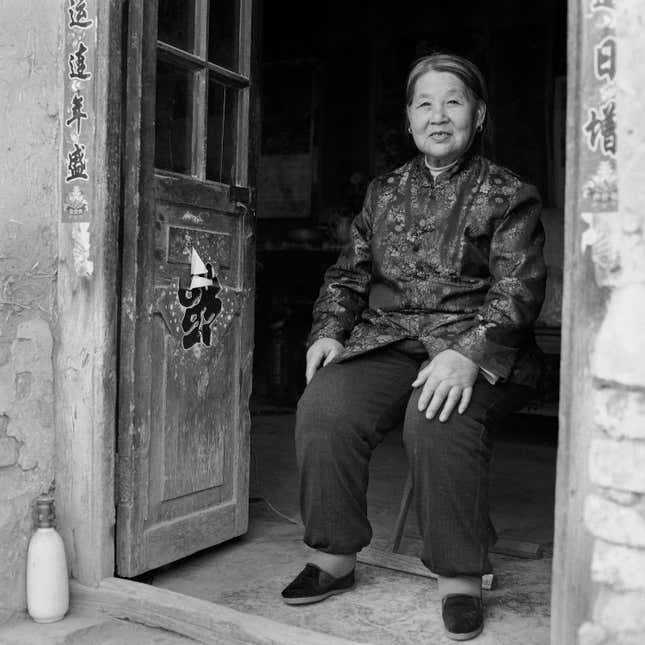

Foot binding was banned for the first time in 1912 during the end of the Qing Dynasty, after Western colonizers and Chinese expat intellectuals labeled the practice culturally backwards. (The culture revolution would reinforce this line of thinking a few decades later.) But some mothers continued to bind their daughters feet in secret. These girls, now elderly grandmothers and great-grandmothers, are the last women alive with bound feet. British photographer Jo Farrell spent close to eight years traveling around China and interviewing them.

Once a mark of beauty and source of pride, bound feet are now stigmatized as a relic of an outdated, unfashionable era.

“Culturally it is not something that is often talked about,” Farrell told Quartz. “Many have never shown their family members or discussed it—this is just not something you do. It is considered a very old tradition that belongs in the past and does not reflect modern China.”

The majority of her subjects come from agricultural communities, and were expected to work excruciatingly long days, hobbled by bound feet or not. Still, among the women she talked to, Farrell personally heard few regrets.

In the beginning, says Farrell, “it gave them more options and control over their destiny. Foot binding in many provinces was the way to secure a better future for your daughter and yourself. A young girl went through a lot of pain during the first years of having their feet bound but they also knew the smaller and well formed foot gave them better opportunities. “

Farrell hopes that through her photos, the experiences of these women will be viewed in a more complex light. These are not exotic curiosity pieces, to be pitied or scorned from afar. “The majority of documentation on this practice is about the beautifully embroidered shoes, the life of luxury and the eroticism of bound feet,” Farrell said. “I want to give a voice to the actual women—through photographs and interviews I tell their stories for future generations to come. It is a reminder even in today’s world about the lengths (typically women) we will go to be aesthetically pleasing, whether we conform to societal norms or fight against them.”