A federal panel is finally looking into one of the least examined problems plaguing the US justice system: are Native Americans living on reservations disproportionately dealt harsher punishments for crimes than other Americans?

Earlier in April, The Wall Street Journal spoke with Ralph Erickson (paywall), a chief federal district court judge for North Dakota. Erickson, an outspoken proponent of sentencing reforms for Native American reservations, is spearheading the federal review. Called the Tribal Issues Advisory Group, the panel is made up of 22 judges and law enforcement administrators, 11 of which are Native American.

“No matter how long I have been sentencing in Indian Country, I find it gut-wrenching when I am asked by a family member of a person I have sentenced why Indians are sentenced to longer sentences than white people who commit the same crime,” Erickson confided to The Journal’s Dan Frosch.

Frosch accounts for this disparity by dissecting the process by which certain crimes are prosecuted on reservations. “Native Americans are typically prosecuted under federal law for serious offenses committed on reservations,” he explains. “State punishments for the same crimes tend to be lighter.”

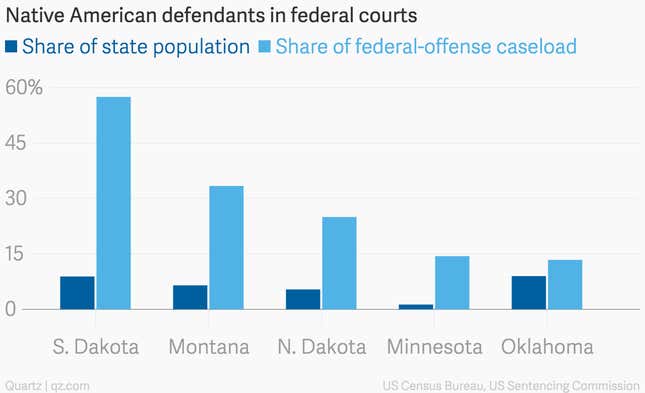

This is not the first time judges have raised concerns over reservation sentencing disparities. The Journal reports that the US Sentencing Commission conducted a similar review over ten years ago—but it resulted in few material changes. In the past five years alone, the number of Native Americans incarcerated in federal prisons has increased by 27%. In South Dakota, the state with the fourth highest percentage of Native American residents, Native Americans compose 60% of the federal caseload, but only 8.5% of the total population.

The trend continues across states with similarly substantial Native populations: they constitute a third of the caseload in Montana, a quarter in North Dakota, 14% in Minnesota, and 13% in Oklahoma, according to Sentencing Commission data.

The Journal’s findings only scratch the surface of this problem, however. Studies on the racial breakdown of incarceration and criminal punishment in the US show Native Americans to be far overrepresented in US jails and prisons. Yet, compared to other similarly disenfranchised groups, media reportage and scholarly analyses of the issue are few and far between.

- Native Americans are incarcerated at a rate 38% higher than the national average, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- Native American youths are 30% more likely than whites to be referred to juvenile court than have charges dropped, according to National Council on Crime and Delinquency.

- Native Americans are more likely to be killed by police than any other racial group, according to the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice.

- Native American men are incarcerated at four times the rate of white men; Native American women are incarcerated at six times the rate of white women, according to a report compiled by the Lakota People’s Law Project.

- Native Americans fall victim to violent crime at more than double the rate of all other US citizens, according to BJS reports. Eighty-eight percent of violent crime committed against Native American women is carried out by non-Native perpetrators.

It’s true that the majority of serious offenses committed by Native Americans are dealt with at the federal level—and this generally entails more severe sentencing. But to claim racialized disparities in incarceration are due to a few differences between state and federal sentencing policy grossly over-simplifies the problem.

Although most American minorities lack much of the communitarian infrastructure that is shown to help mitigate crime, Native Americans are particularly deprived. The federal government can take active steps to resolve Native American overrepresentation in prisons and the juvenile corrections system by funding child and family services on reservations, as well as tribal juvenile and addiction rehabilitation centers. (Seventy percent of Native Americans convicted of violent crimes claim they had been drinking at the time of the offense, according to the LPLP.)

“I commend the Commission for creating a mechanism to develop insights and information that have the potential to impact the lives of our citizens in Indian Country,” Judge Erickson said in a statement released by the USSC in Feb. 2015. Hopefully, the Sentencing Commission’s second attempt will be more successful than its first. Because “insights and information” abound—what Native communities need now is real action, leading to real change.