When Google’s co-founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, decided to set up a venture-capital fund back in 2009, they chose a relatively little-known neuroscience graduate, entrepreneur, and biotechnology investor to run it. His name is Bill Maris, and over the past five years, he’s become one of the most important and powerful men in Silicon Valley.

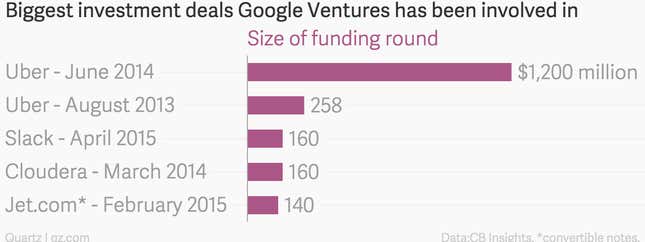

Each year, Maris has $400 million to invest in startups. So far, Google Ventures, of which he is managing partner, has poured $2 billion into 300 of them, including the likes of Uber, the car hailing service; Slack, the office messaging system; Medium, the blogging platform; and a host of life-sciences and health companies.

Corporate venture capital funds have been around for years. Chip maker Intel, for example, has had one since 1991. They serve the dual purpose of enabling tech companies to earn returns on their vast cash reserves, and help them keep abreast of innovation in ways that giant lumbering corporations often struggle with.

But Maris and Google have embraced corporate venturing with a vigor that few others can match. According to CB Insights, Google Ventures was the fourth most active VC fund of any kind last year. Six of its portfolio companies have successfully gone public. Fourteen are so-called “unicorns”—still private, but valued at over $1 billion apiece. Only a handful have failed; of those perhaps the most notable is Secret, the anonymous messaging app that closed down last week.

Quartz caught up with Maris this week to discuss all things Google Ventures. The discussion has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Quartz: With Google Ventures, there is this whole question around conflicts of interest. You guys invest in Uber, but Google may have competing businesses to Uber. You invest in Nest; Google ended up buying Nest. How do you manage that?

Maris: I would draw a really big distinction between competition, or potential competition, and a conflict of interest. A conflict of interest implies wrongdoing, whereas competition is really healthy. I set up Google Ventures specifically to invest in things that might compete with Google. In all of the 300 investments, never once has Google tried to influence an investment. And when we set it up, Larry and Sergey don’t have a say. That was intentional. And I said, the first day Google tries to influence those things will be my last day here.

The whole business has to be based on our interests being aligned with entrepreneurs. If there is any divergence there, like you see with some venture funds that are raising really large funds then their interests start to go away from what the entrepreneurs’ interests are.

If a company becomes big enough where it is actually in competition to Google, that is a huge win [for Google Ventures]. That’s like a great investment that we have made. I would love that, it would be really exciting and we would celebrate that, because we are trying to build big important companies that sometimes have big overlapping interests.

There is always some conjecture about whether the objective of Google Ventures is financial returns or something strategic for the parent company.

I can make it very clear: I get paid if we make good investments. And if we don’t I don’t get paid. I have no incentive to sell our companies to Google, the entrepreneurs get to decide that. We are minority shareholders. I get no special credit if Google buys Nest. I get no special credit if they don’t. In fact we recuse ourself from those discussions, and we have sold more companies to Facebook and Yahoo than to Google.

Have you disclosed your returns?

No. I mean, what fund does? But they are really good. We don’t put those numbers out there but, I will say that from where we started, when other funds laughed at us across the table, saying “what do you know about venture?” to where we are now, it has been a huge gain, something I am really proud of.

So what does Google get out of Google Ventures?

On the one hand, financial return is the objective. That’s how we get measured, but there are many unintended consequences that Google benefits from. Hundreds of startup founders who have reason to talk to people at Google, build relationships. Those companies have stronger relationships with Google as a result of our investment than if they didn’t. That gives Googlers and engineers a reason to say “I want to work on an interesting product in my 20% time“. Well, here are 300 companies to choose from that have already been vetted. That’s one kind of benefit.

Another is participation in the startup ecosystem, being part of the lifecycle. Google was a venture funded company. Being part of that brings an energy to the company.

More than one third of the money Google Ventures invested last year went into life-sciences companies. Can you explain the over-arching investment thesis behind that?

This is the “transistor moment” for life sciences. By that I mean, what the transistor enabled for computation resulting so far in this [pointing to his mobile phone]… that’s very similar to what’s happening in life sciences. The sequencing of the human genome started in 1991, ended in 2004. We didn’t have much hope of curing cancer before you could sequence the genome. We’ve been at it for 15 years and people say “Oh, cancer, we are making no progress.” Give it some time!

Now is the moment where change is going to happen at such a pace it will be as unpredictable as this was [points to the mobile phone again]. In 1970, you could imagine people could talk to each other… but you wouldn’t imagine Instagram—there’s like several layers deep you have to go to imagine [that]. So things are going to happen in the life sciences that are more important [than in consumer tech] because it means people will suffer less and die less.

This coming wave that’s about to happen [in life sciences] is under-appreciated. It’s not as attractive to talk about, it’s harder to understand, to communicate to people, it’s not as celebrated in a lot of ways.

What are the other themes that influence how you apply capital in the portfolio ?

One, we care a lot about [the founders] we are investing in. The extent we can understand their motivations and their values—you don’t always get it right but you try. That’s really important because you are building a relationship that will last often for years. You want to work with people you are excited about and they are excited about you. It’s a two-way street.

When you think we have 300 companies, with tens of thousands of employees, we have a real opportunity to share our values with those companies, not just corporate values, but transparency and how to treat people. Just this past week if you asked me about our top 25 investments, what percentage of those boards are female, if you said 10% you would be off by a factor of two. It’s 4%. So that’s an opportunity.

I look at our investment team, we have two female partners out of 15, we have an offer out to a third… and that’s really kind of egregious. It’s sad. So I look at our own team, and to our portfolio and it’s a chance to say to them, “We can do better than this.”

You recently invested in Kobalt, a fascinating company, but one that doesn’t seem to fit the profile of what you would invest in.

I actually think it fits perfectly in what we want to invest in. It’s a disruptive company changing the nature of an old stodgy industry [music publishing]. Willard [Ahdritz, Kobalt’s CEO] is a very dynamic, engaging CEO, he describes himself as a crazy Viking. He is part of that interesting group of Swedes in the music business.

I also happen to be married to a professional touring musician, a singer-songwriter… and I discovered how messed up the music business is. Is it even a business? In what other industry can you provide a product, get no information on who bought it, how many times it sold, and then a year later get a cheque with no explanation? I think there is a lot of corruption in that payment chain. Kobalt wants to bring transparency to that.

Kobalt was your first international investment. Are there more plans to invest offshore and where? In Asia?

In the very near future we will have some more [investments] in Europe. Right now our focus is the US, Europe, Israel. Its important to have some people there locally; we don’t have anyone in Asia right now. But it’s not a part of the world we intend to ignore. It’s just a matter of, “Just give me a little time!”

The great thing about the world today is that there is innovation everywhere. [Spotify CEO] Daniel Ek has built a really important company not based in the US, not based in London [but in Sweden]. So there’s a lot of opportunities and we would be foolish to think they will come to us and we don’t have to look hard.