It’s difficult to overstate how serious Russia’s alcohol problem is.

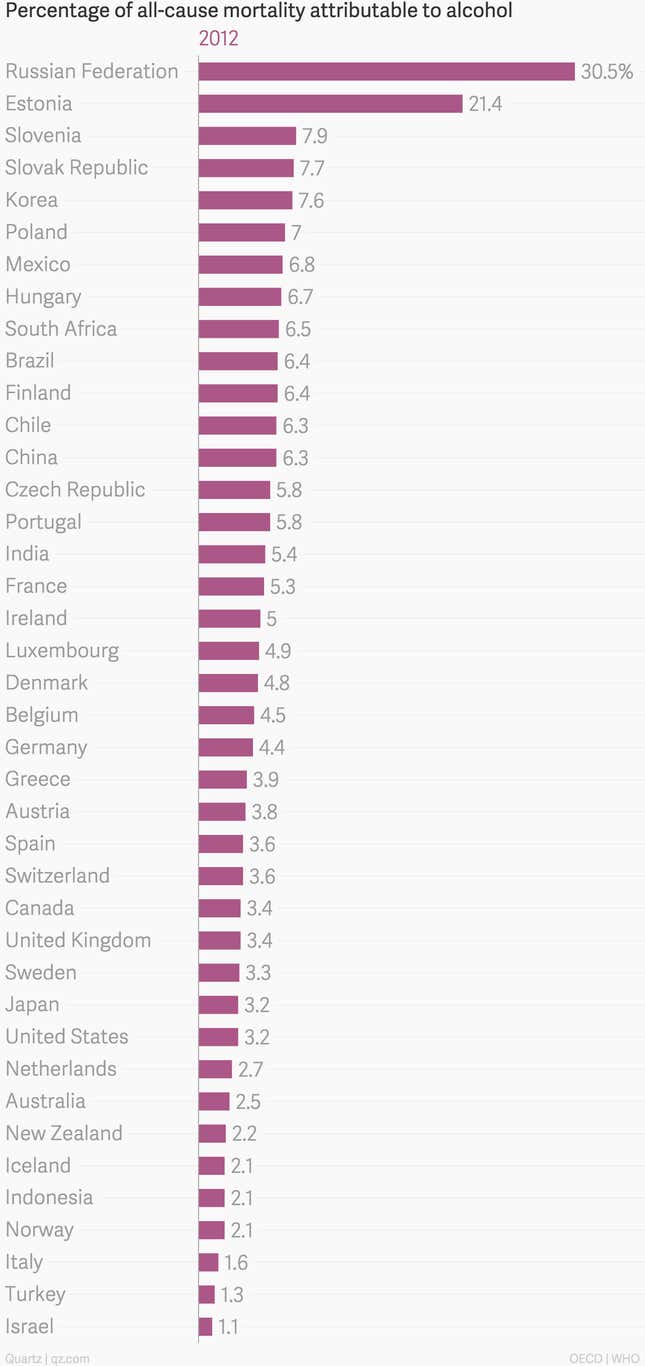

More than 30% of all deaths in Russia in 2012 were attributable to alcohol, according to WHO data crunched by the OECD. That’s by far the highest among the nations it tracked.

Russian drinkers die a variety of deaths. Alcohol poisoning. Cirrhosis. Accidents. Suicide.

The result? Russians live some of the shortest lives in any large economy. Life expectancy for a Russian man was roughly 65 years in 2012, compared to 76 years for the US and 74 for China.

Part of the reason is cultural. Hard drinking has long been a Russian habit. A paper published in 2013 found that relatively high levels of alcohol-related deaths can be found in Russian data going back to the late 19th century.

But the mortality rate surged amid the collapse of the Soviet Union, especially among men, largely thanks to more drinking. The economic collapse of the former Soviet republics during the 1990s is unparalleled among major economies since World War II. By some estimates the region’s GDP fell by roughly 40%. The ruble fell 99% against the US dollar (pdf, p. 159) between December 1991 and December 2001. Many turned to alcohol amid economic chaos.

Another reason is low prices. In the 1990s, Russian vodka got very, very cheap. This paper (pdf), published in 2010, argues that real vodka prices plummeted in Russia in the early 1990s, as nascent competition in the industry led to overproduction, excise tax went uncollected (the tax authorities were in disarray) and misguided government policies held vodka prices down amid disastrous inflation. (Keeping vodka cheap was viewed as a political priority.) Daniel Treisman, the political economist behind the paper, writes:

In December 1990, the average Russian monthly income would buy 10 litres of ordinary quality vodka; 4 years later, in December 1994, it would buy almost 47 litres. Initially, vodka became much more affordable because of a dramatic drop in its relative price.

Drinking deaths are only part of the reason that the Russian demographic picture looks so dire. Birth rates are another. In recent years, the working-age population has also begun to decline quickly, weighing on the productive capacity of the economy. Putin’s state has taken action to stabilize Russia’s demographics, including instituting payments for child-bearing. The results are seemingly mixed (pdf, p. 4).

As bleak as things are, they’re not without hope. Policy changes to alcohol licensing and sales laws instituted in 2006 seem to have had some success in decreasing vodka consumption and marginally reducing deaths, at least according to one study. And if official Russian statistics are to be believed, birthrates have bounced up a bit, the population is no longer shrinking, and alcohol-related deaths are on the decline. These claims, though, are pretty controversial, as anything involving Russian official statistics tends to be.

Either way, a glimpse at the chart above shows just what a tragic outlier Russia remains. Even if it’s begun to tackle its drinking problem, it’s still a long, long way from bringing it down to manageable proportions.