In 2009, Saudi Arabia was named the most dangerous place in the world to drive by the World Health Organization. And even though there’s a ban on women driving in the country, a disproportionate number of the road fatalities are female teachers.

Last year, Saudi Arabia’s highest-grossing female artist Manal Al-Dowayan created Crash (2014), a visualization of the ongoing tragedy told through data. “It’s become part of the tea-time talk in the majlis, the women’s area,” she says. “It’s always Oh, did you hear about so-and-so teachers who died in the so-and-so region? Oh those poor things.”

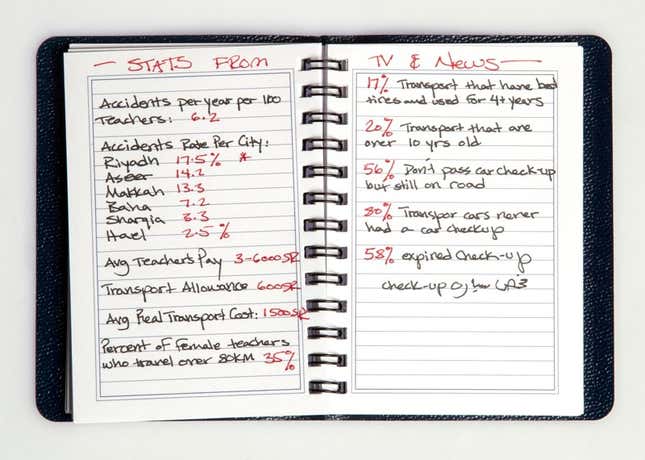

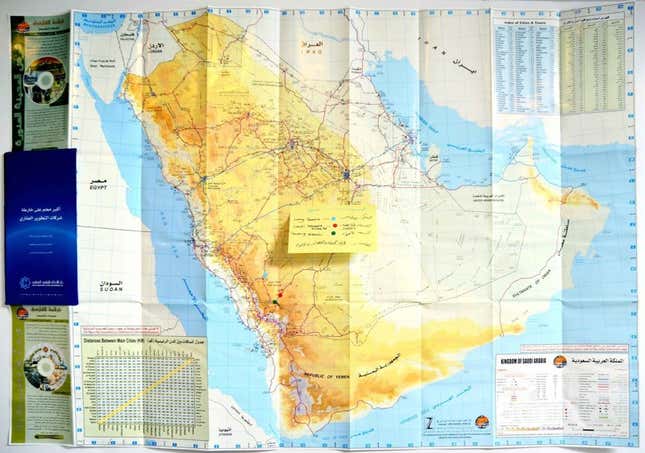

The problem is the commute. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia provides state-funded schoolteachers to even the most rural villages, which means that many teachers must travel long distances to work. Male and female teachers are hired in roughly equal numbers for elementary and intermediate school, but men can drive themselves to work. Women, on the other hand, do not have the right to drive, so female teachers tend to carpool in hired cars and taxis.

“There are of course deaths because of remote areas, unsafe roads, ambulances taking forever,” says Manal. “Car accidents exist for both genders, but more for women because there are always six or seven women per car, so the numbers are much higher.”

Comprehensive reviews are scarce, but a 2008 report released by the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology and based on data from the late 1990s, concludes that commuting female teachers are 50% more likely to get in a crash than the average Saudi.

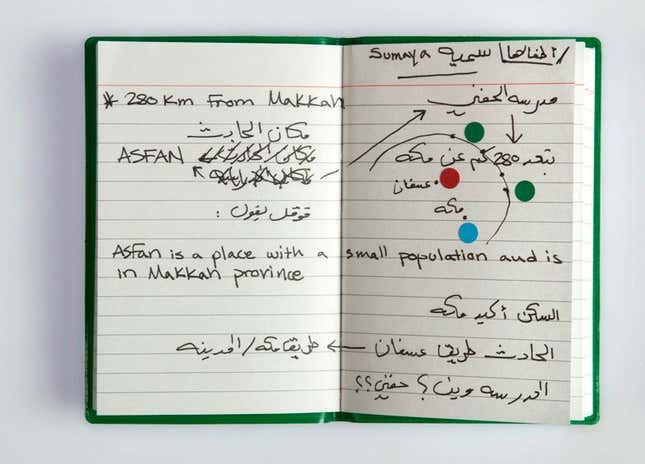

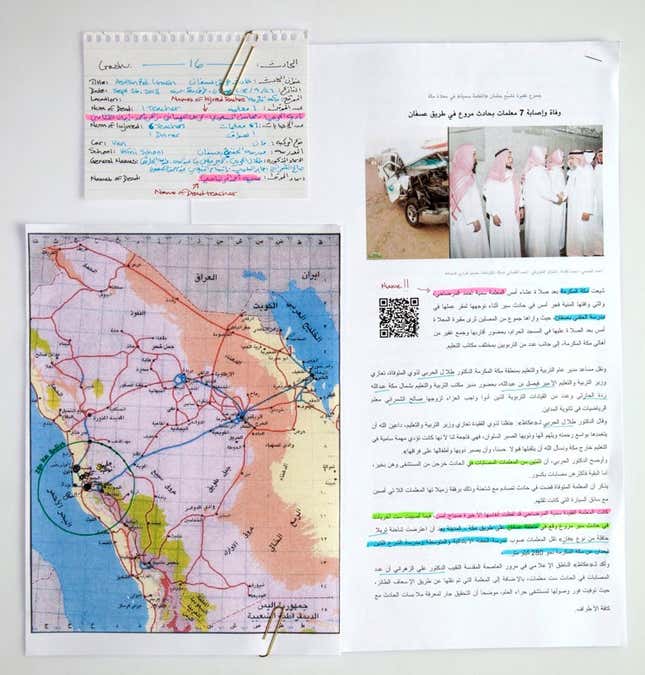

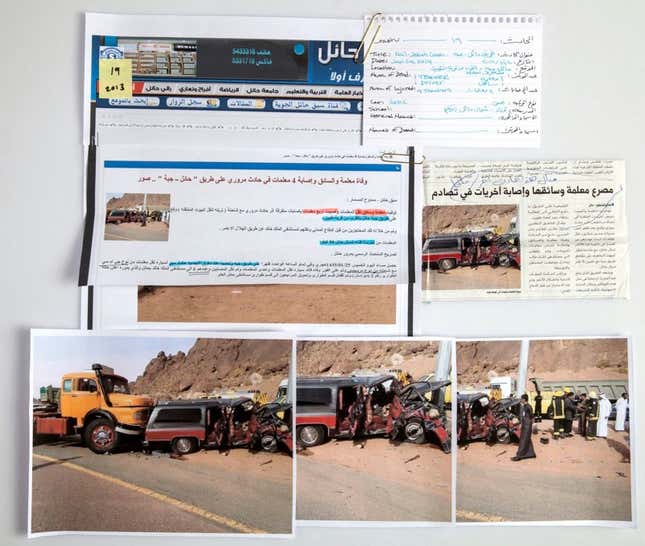

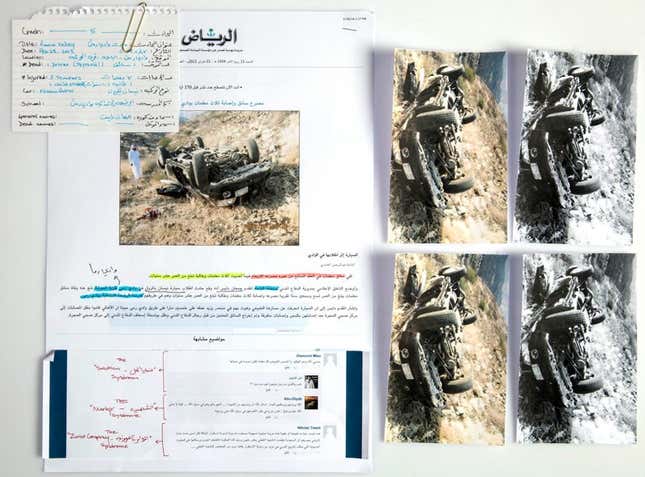

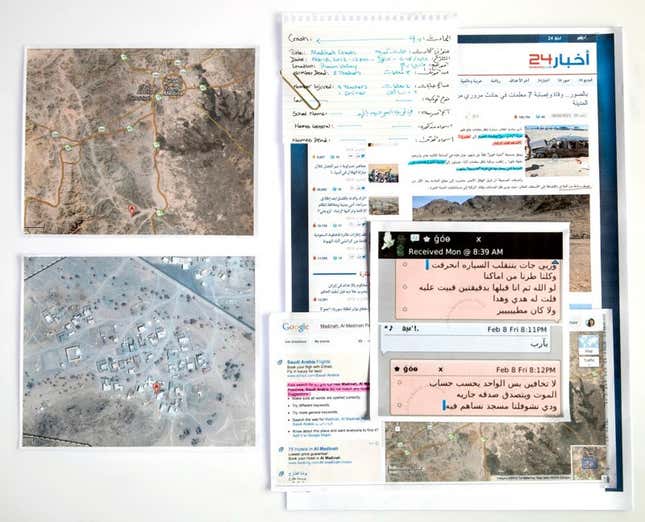

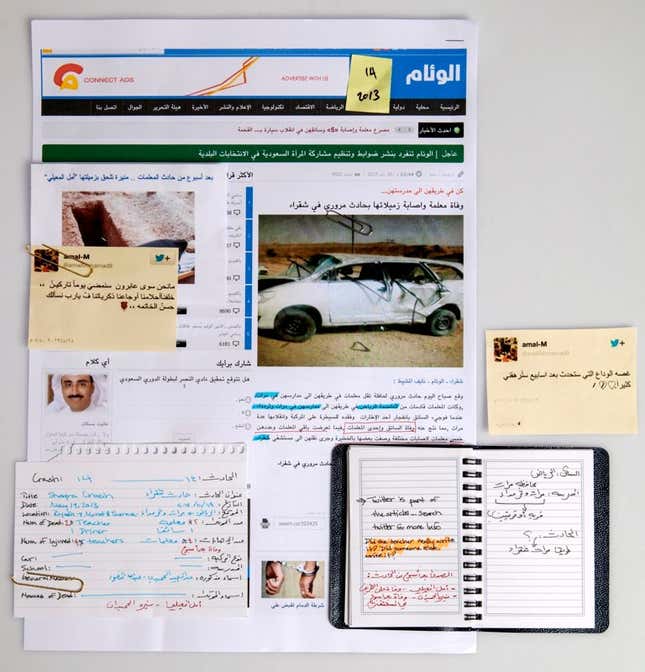

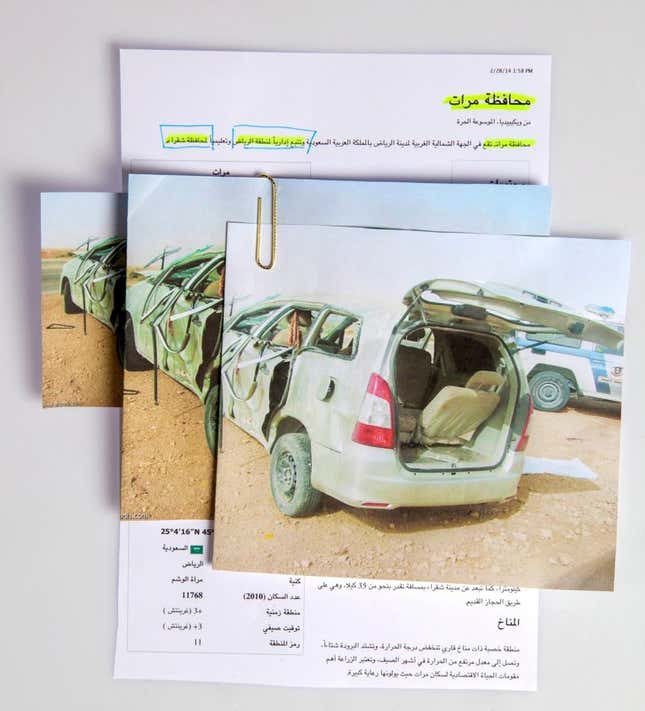

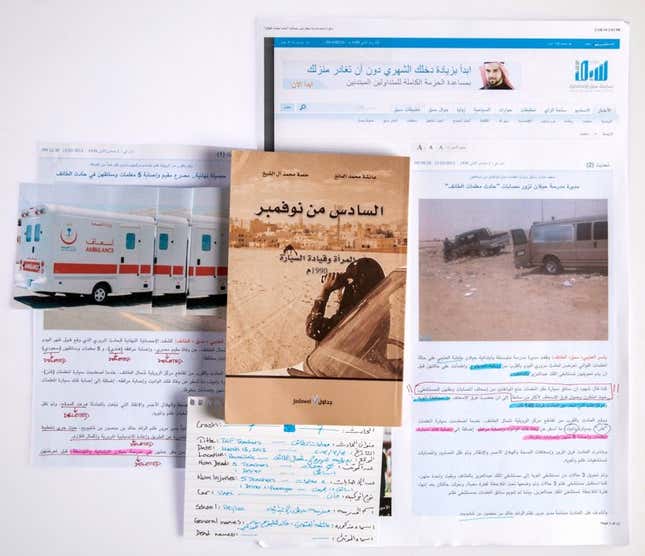

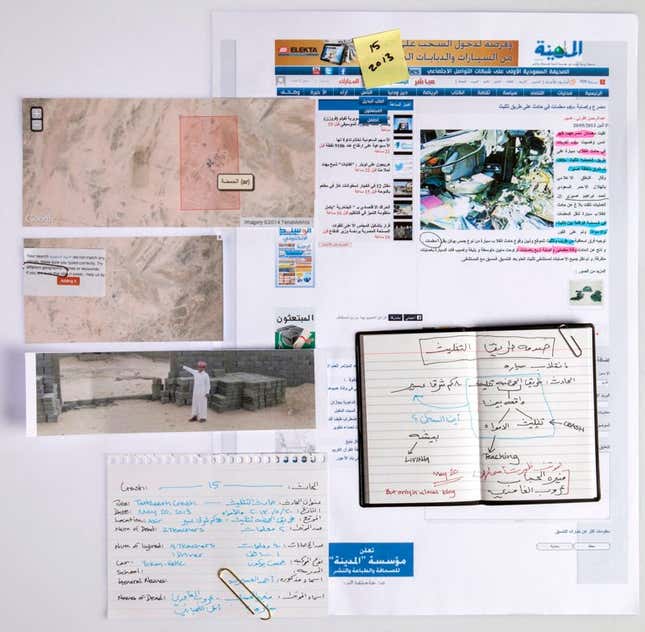

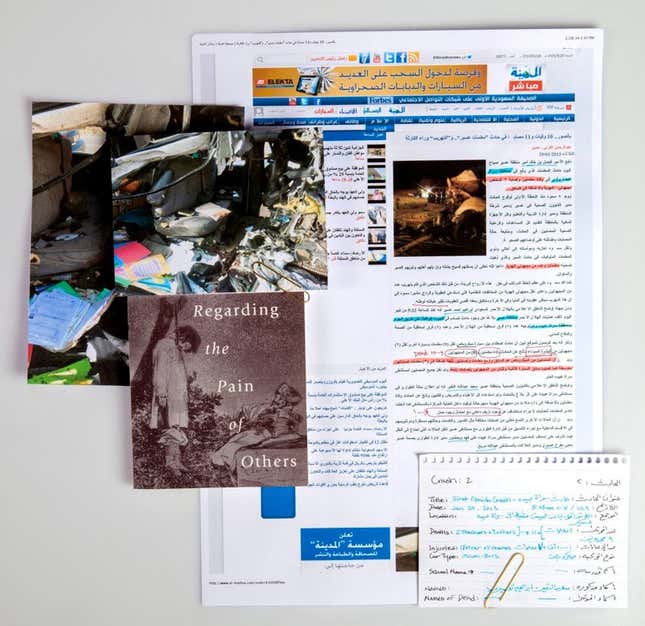

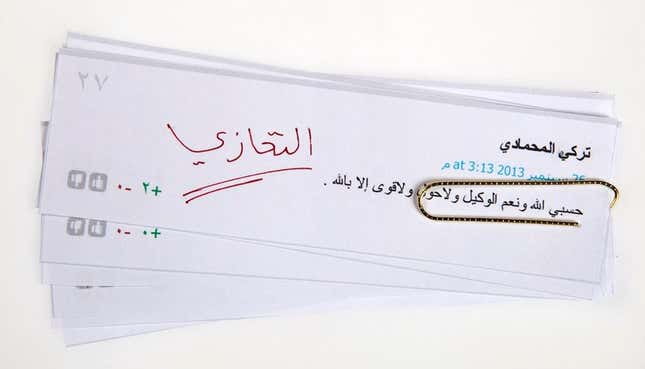

Crash gathers documents (maps, photos, newspaper reports) from 70 car accidents involving female teachers from January to December 2013. “Within that sample,” notes Manal, “About 50 women died, and only twice their names are mentioned.”

“Names are a social taboo,” explains Manal. “In Saudi culture, or maybe Islamic culture, women are required to cover their faces, lower their voices, not appear, be more modest. And there is a phenomenon that reaches all the way through India in which men do not pronounce women’s names in front of men.”

Newspapers are guilty of bowing to convention, too, even though it is not legally or religiously mandated. “Journalists take it upon themselves that they will not publish a woman’s name,” says Manal. “For fear that their tribe or family will be embarrassed that her name appears in public.”

“For me, when you don’t mention names, you’re erasing their identity,” she says. “By doing that, you’re dehumanizing them, and allowing a space for abuse.”

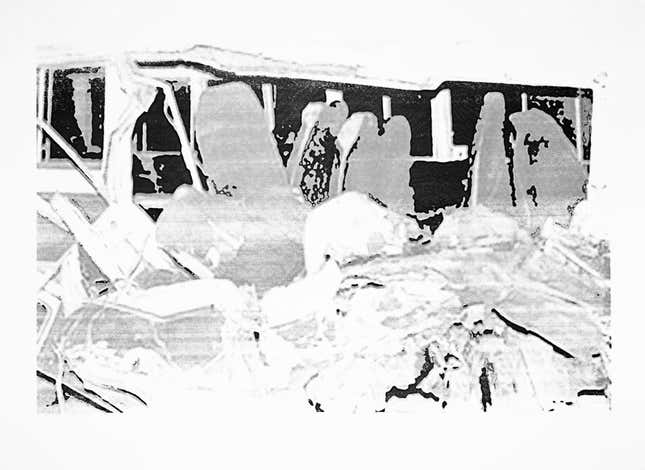

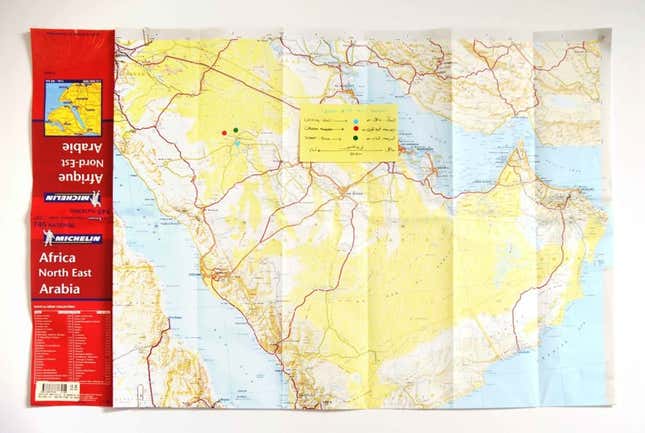

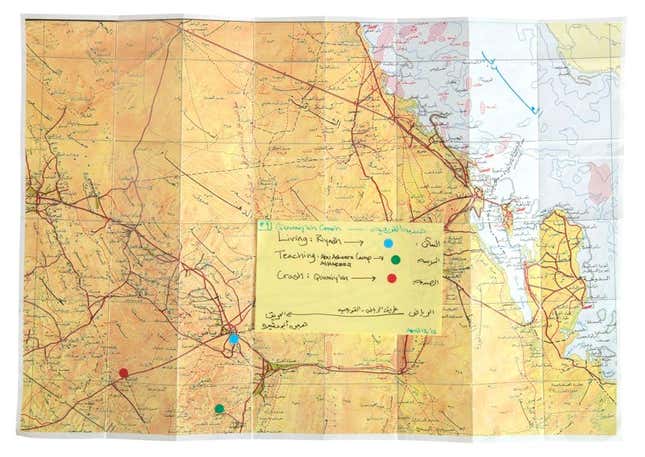

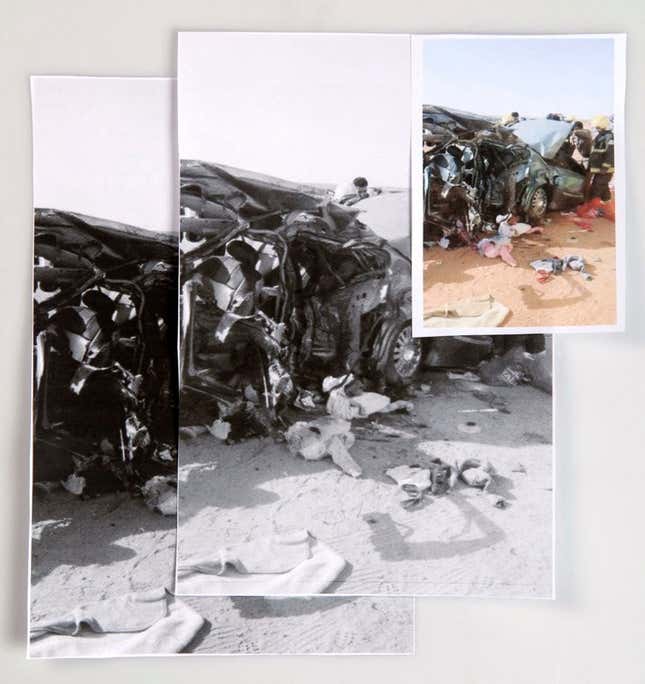

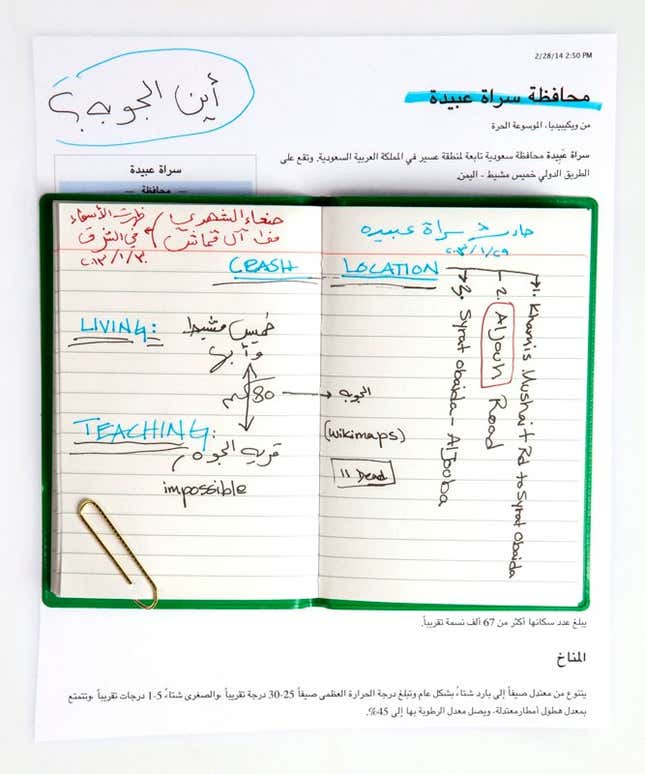

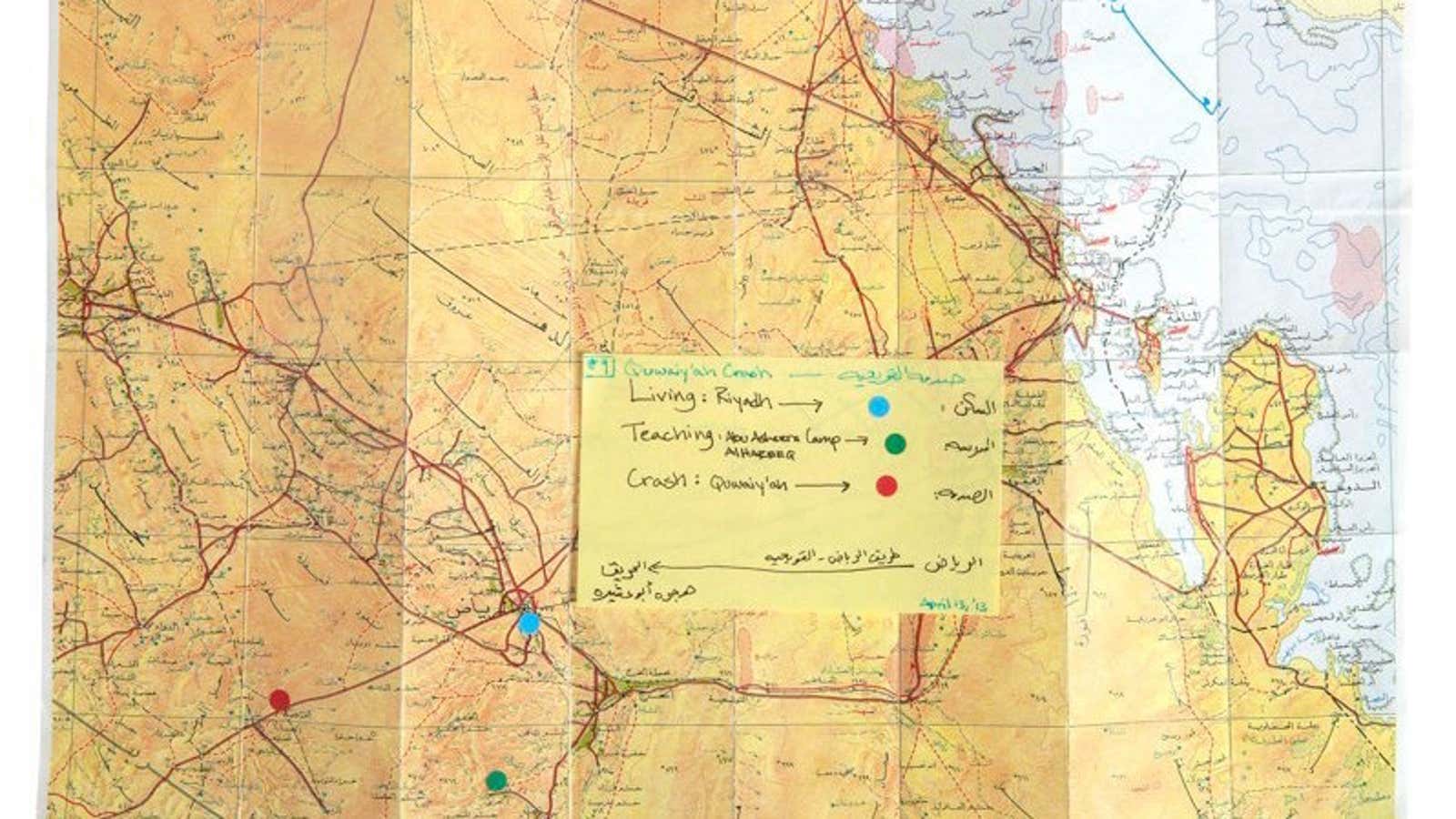

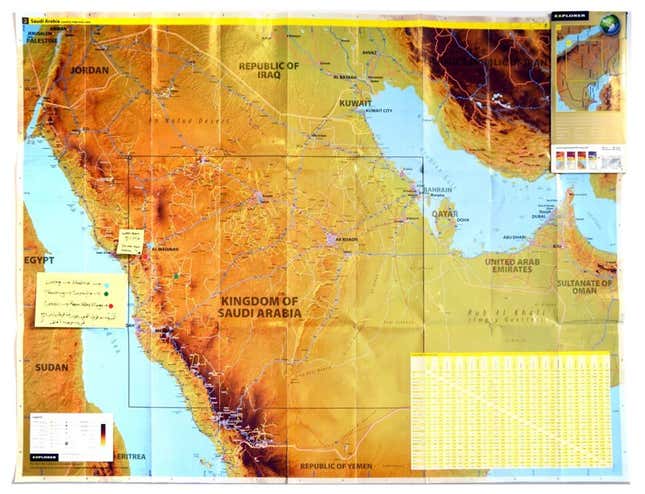

Crash documents an effort to understand tragedy more deeply, and to memorialize its anonymous victims, by composing a chorus: a series of sheets of real statistics; a series of maps plotted to show the distances between where car crash victims were teaching, where they lived, and where the accidents happened; and a series of massive silkscreens of after-the-fact newspaper photos.

By mapping, tracing, and analyzing the accidents, Crash also attempts to rectify the injustice that social etiquette scrubs dead women from the public record.