There are some 60 million kilometers (37.3 million miles) of roadways in the world, just sitting there. But adapting these surfaces to do anything besides passively carry traffic has proved difficult and prohibitively expensive.

Past attempts include trying to convert the vibrations on roads into electricity. But this technology is only economically feasible on the busiest thoroughfares, which account for a tiny proportion of the world’s huge network.

Others have tried to capture and store heat energy during summer and feed it through the road when the weather changes to keep it ice-free. There is even a working test-patch in Hiroshima, Japan.

But the idea that has gained the most traction in the last few years is to embed solar cells in roads. In 2014, an American couple launched the Solar Roadways project and collected more than $2 million on the crowdfunding site Indiegogo. Their effort, however, is much farther from reality than the Netherlands-based consortium SolaRoad, which has been operating a 70-meter (230-foot) cycle path that generates enough electricity for one or two households.

Installed in November 2014, the results after six months of field testing are positive. In fact, the road has been generating slightly more energy than SolaRoad predicted at its lab.

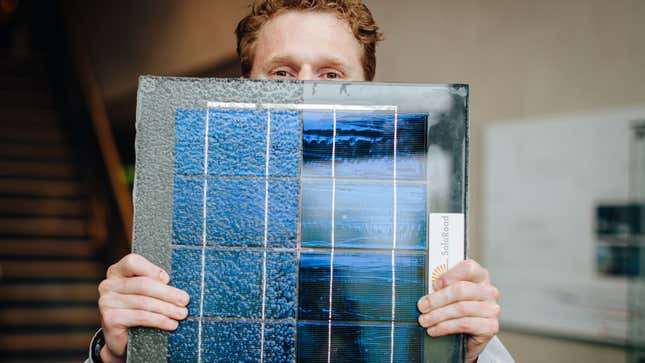

The principle is simple. The photovoltaic cells that generate electricity are protected by glass on the top and supported by rubber and concrete at the bottom. The glass, apart from letting light through, has properties similar to asphalt or concrete: it is durable, glare-free, and skid-resistant. Each unit is connected to a central system, where the electricity generated is fed to the grid.

The company claims that a 12-ton truck could safely ride over the road. On the test road, however, only some 150,000 cycles have put it to the test so far. Apart from some minor chipping, the roads have continued to work well. The next step is to build roads in other local councils—maybe even a highway or two.

Making watts while the sun shines

Where SolaRoad stands out from competition is in the economic case for their business. For starters, the four companies involved in the consortium complement each other well: TNO is the research center, Ooms Civiel is involved in road construction, Imtech has expertise in electrical integration, and the province of Noord-Holland is supporting the project as a future customer.

The public-private consortium has invested $4 million in the project, which includes the cost of building the test road, and is committed to scaling up. The group’s unique selling point is not so much the innovation of its core technologies, which have been around for many years, but its ability to integrate and manufacture solar-road panels in bulk.e.

Another strength is in its focus. The American Solar Roadways project wants not only to harness solar energy, but also use the panels to provide light and heat for the roads on which they sit. “Instead, SolaRoad is focused on the single objective of generating electricity from roads,” Sten de Wit, a senior adviser at TNO, told Quartz. “If we are successful, we may look into lighting or heating.”

SolaRoad won’t divulge what it costs to make their roads right now, but the goal is to build something that can last for 20 years. It says the extra cost when compared to asphalt or concrete roads will be recouped in the first 15 years by the electricity generated, and the extra revenue generated in the five years after that will make its solar-powered roads economically attractive. Falling solar-cell prices will only make this case stronger.

Among all the newfangled ideas to make roads do more, SolaRoad appears to be on the most promising path.