This post has been corrected.

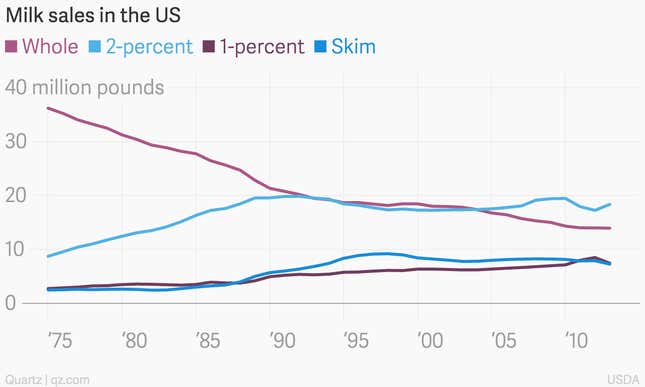

Once upon a time, Americans drank a lot of whole milk. But when the anti-fat movement of the 1980s took hold, no-fat or lower-fat milks saw their popularity rise along with the cream that would soon be skimmed off the top. For most people, creamy, nutritious, delicious whole milk, like the milkmen who used to deliver it, became a relic of the past.

For all the debate surrounding the latest recommendations from the committee that proposed federal dietary guidelines, the group’s endorsement of low-fat and fat-free milk over whole has garnered little attention. This suggests that while many of us scoff at the misguided anti-fat crusades of recent years (nuts to you, 1980s!) whole milk remains an unpopular outlier. And that’s just ridiculous.

Surprise! Dairy fat actually helps avoid obesity

Though it would seem to follow that consuming less fat would lead to being less fat, that’s not quite what the science says, at least when it comes to dairy—even if whole milk is more caloric than skim.

In 2006, a study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition looked at the role of dairy consumption in weight regulation for 19,352 Swedish women between the ages of 40 and 55. Data was initially collected between 1987 and 1990, and then again in 1997. It found that for the women in the study, eating one or more servings a day of whole dairy products was “inversely associated with weight gain,” with the most significant findings for normal-weight women consuming whole milk or sour milk.

In 2013, the Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care published findings from a study that tracked the impact of dairy fat intake on 1,782 men. Twelve years after researchers took the initial measurements, they found that consumption of butter, high-fat milk, and cream several times a week were related to lower levels of central obesity, while “a low intake of dairy fat… was associated with a higher risk of developing central obesity.” (Central obesity means a waist-to-hip ratio equal to or greater than one—i.e. big in the middle.)

Still skeptical? Shortly after that study came out, the European Journal of Nutrition published a meta-analysis of 16 studies on the relationship between dairy fat, obesity, and cardiometabolic disease. (A meta-analysis combines findings from multiple, independent studies, and when done correctly, provides better coverage of a question than any single study usually can.) Its findings will be revelatory for anyone who drinks skim for weight control:

The observational evidence does not support the hypothesis that dairy fat or high-fat dairy foods contribute to obesity or cardiometabolic risk, and suggests that high-fat dairy consumption within typical dietary patterns is inversely associated with obesity risk.

While not conclusive, the results “may provide a rationale for future research,” the study’s authors noted.

This “dairy paradox” begs the question: Why does eating food with more fat lower the risk of obesity?

One possible explanation, says Walter Willett of the Harvard School of Public Health in an interview with NewScientist, is that “the full-fat version provides more satiety,” meaning, if you drink full-fat milk with your breakfast, you’ll be less likely to grab that doughnut an hour later.

But that’s not the only plausible answer. “It is also possible that some of the fatty acids in milk products have an additional effect on weight regulation,” he says. Plus, a lot of low-fat or fat-free dairy products compensate for the lost flavor by adding in sugar—and that “will almost certainly induce more weight gain than the full fat versions.”

Relax about the saturated fat

Whole milk is 3.25% fat. A single cup has 8 grams of fat, including 5 grams of saturated fat—a substance long vilified as a cause of heart disease. The World Health Organization and the American Heart Association both continue to advise low consumption of saturated fats, but science is challenging the conventional wisdom on this, too.

One meta-analysis, published in 2010 in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, reviewed 21 earlier studies and found “no significant evidence for concluding that dietary saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease or cardiovascular disease.” Another, published in 2014 in the Annals of Internal Medicine, reviewed 76 studies and came to a similar conclusion: The evidence did not support a recommendation of low consumption of saturated fats.

A measured interpretation of all this goes back to the old adage: Everything is fine, in moderation. Eat too much of anything and it will probably hurt you, especially because it is most likely replacing other, more healthful foods.

“What really is the bottom line,” says Keri Gans, a registered dietician nutritionist and author of The Small Change Diet, “is we need to look at the total diet.”

In other words, if you’re eating bacon at breakfast, you probably shouldn’t drink a glass of whole milk with it, she says.

But if you’re choosing between the two, go with the milk. Unlike the bacon, Gans says, whole milk has not just saturated fat, but nutrients as well. With bacon, “you’re really not getting a lot of nutrition—you’ll be getting a whole lot of sodium.”

Your body needs fat to absorb vitamins A and D

Anyone who remembers the Got Milk? ad campaign, probably also remembers the regularly mentioned line about milk having nine essential nutrients: vitamins A, D, and B, calcium, protein, potassium, riboflavin, niacin, and phosphorous. One 8-oz. glass provides between 10% and 30% of the recommended daily intake for all but one of these. (For niacin, it’s 1.1%.) It’s worth noting, however, that milk is not necessarily the best source of any of them, as Alissa Hamilton lays out in her book, Got Milked? The Great Dairy Deception and Why You’ll Thrive Without Milk.

But what those people drinking skim milk may not realize is that without the fat, they may be missing out on the benefits of vitamins A and D, both of which are fat soluble. That means the body needs fat to absorb them.

Vitamin A, which benefits your skin, vision, teeth, soft tissue, and mucus membranes, naturally occurs in whole milk, but when the fat is removed, most of the vitamin A content goes with it. Skim, 1%, and 2% milks are now fortified with synthetic vitamin A to bring them back up to whole milk’s level—but still, without the fat, the vitamin A won’t do you much good.

Lower-fat milks have a similar problem with vitamin D, which does not occur naturally in milk, but has been added in in the US since the 1930s to promote bone health. You can get vitamin D by spending time in the sun, but depending on your season and location, you might not be getting sufficient amounts. You can supplement your intake with milk, of course, but vitamin D is also fat soluble—no fat, no benefit—so a glass of skim on its own makes for a poor delivery mechanism.

These vitamins can still be absorbed by the body, Gans says, if there’s fat coming from somewhere else, like eggs—or even that bacon. But the fat needs to be consumed during the same meal to be a benefit. So if you are drinking a glass of milk as a snack, be aware that skim won’t give you all the vitamins you’d get with a glass of whole milk.

Whole milk is closer to a ‘whole food’ than skim

Health advocates like to promote eating “whole foods”—meaning foods that haven’t been broken down into their underlying components and then put back together again in new shapes and flavors.

Nearly all milk sold (legally) in the US is processed, because it must undergo pasteurization, a heating process that kills pathogens. Outside of a small group of raw milk activists, this is generally accepted as a positive. “Yes, milk is processed,” says Gans, “but in the good sense of the word.”

Lower fat milks go through more processing than their whole cousin. As Kimberlee J. Burrington of the Wisconsin Center explained to Chow.com, taking the fat out of milk is a high tech endeavor:

Inside the [centrifuge] machine is a series of discs with vertically aligned holes stacked together. The discs spin at high speed. The fat moves inward in the separator and the skim milk moves outward. It is a physical separation based on the difference between the density of the fat versus [that of] the skim milk.

For 1% or 2% milk, fat is then added back in through additional processing, the type of which depends on the dairy, along with the vitamins that came out with the fat.

There is nothing necessarily wrong with this processing, and Gans thinks referring to whole milk as “less processed” may be confusing. But because making low-fat and nonfat milks means taking parts out of it and then putting them back in, whole milk qualifies as the least-processed kind—and besides, it’s also the most delicious.

Correction: An 8-oz. glass of milk contains between 10% and 30% of your daily value of eight essential nutrients, not nine as an earlier version of this post stated. (It contains only 1.1% of your daily value for niacin.)

The photograph above was taken by hjhipster and shared under a Creative Commons license on Flickr. It has been cropped.