This post has been updated.

The only son of a lawyer, Shoaib Ahmed Shaikh grew up in a religious, middle-class Pakistani household with one ambition: He wanted to become the richest man in the world.

“Even richer than Bill Gates,” Shaikh told his employees in a speech last year.

While reading for an MBA from Karachi’s well-respected Institute of Business Administration, he decided to strike out on his own and build a company—Axact.

“Back in 1997, when Yahoo! had just begun to gain momentum and two Stanford students were yet to be called the founders of Google, Axact began its operations from a single room with less than 10 team members,” he told Pakistan’s Newsweek magazine in a 2013 interview.

Today, Axact claims to be the “World’s Leading IT Company” (by what measure no one is quite sure) with a “global presence across 6 continents, 120 countries and 1,300 cities with more than 25,000 employees and associates.” Axact, by its own account, has “10 diverse business units (that) offer more than 23 world class products,” with more than two billion users worldwide and a customer base of 40 million.

But, according to an investigation by The New York Times, Axact rakes in millions of dollars in revenue from a rather sinister business: Fake online degrees.

“Axact does sell some software applications,” the newspaper reported. “But according to former insiders, company records and a detailed analysis of its websites, Axact’s main business has been to take the centuries-old scam of selling fake academic degrees and turn it into an Internet-era scheme on a global scale.”

The company, the Times reports, employs a sales team of young, well-educated Pakistanis to aggressively sell everything from bogus high school diplomas to doctoral degrees. Social media has helped to add a mask of legitimacy to the operation, including the use of fake LinkedIn profiles for made-up professors of Axact’s universities.

In a response to the Times report, Axact said in a statement that it “condemns this story as baseless, substandard, maligning, defamatory and based on false accusations and merely a figment of imagination published without taking the company’s point of view.”

“All ten business units of Axact are completely legitimate, legal and committed to enhancing the quality of IT services across the world,” the statement added.

A tiny tax bill

Exactly how Shaikh converted Axact from a small garage startup into an apparently thriving firm that, according to its website, is “three times larger than any other private sector company in Pakistan” is unclear.

In his 2013 interview, Shaikh entirely skipped discussing the early days. “Following Axact’s initial success, the organization expanded its scope to offer back-office services, ERP applications, and design services, among other things,” he said. “Axact’s excellence has made it a giant in the online design industry.”

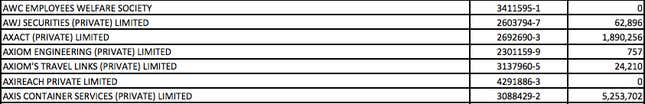

Axact, as per the records of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP), was registered on June 06, 2006 in Karachi. The company, according to SECP’s 2010 records (downloadable Excel sheet), had paid up capital, or fully-funded shares, of only Pakistani Rs. 6 million ($58,860).

And in 2014 financial year, this apparent Pakistani private-sector behemoth paid just Pakistani Rs. 1.89 million ($18,543) in taxes, according to government’s tax directory (pdf). Last year, the corporate tax rate in the country stood at 34%.

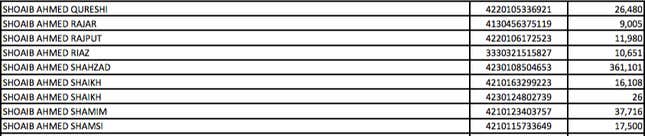

Shaikh’s income tax payment, as per the directory, was even more extraordinary: The chairman and CEO of Axact paid all of Pakistani Rs. 26 ($0.26) in 2014, a fact that was made public by journalist Ahmad Noorani.

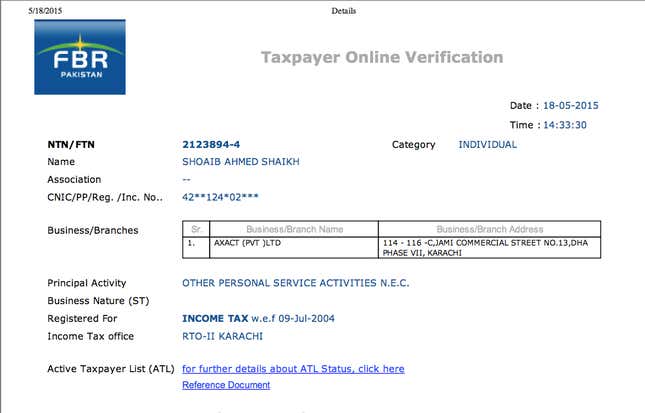

The second “Shoaib Ahmed Shaikh” named in the list below, corresponds to the Computerized National Identity Card (CNIC) number 4230124802739. That number links back on Pakistan’s Online Taxpayer Verification website to an executive at Axact (see left).

The lowest individual tax rate (pdf) in Pakistan is 5% for earnings above Pakistan Rs. 400,000, meaning that Shaikh’s total declared income, based on his tax rate, was just Pakistan Rs. 400,520, or about $3,929.

How Axact woos employees

Going purely by his income tax payments, you would think that Axact’s chief would be quite a frugal man. But Axact employees are treated well.

An engineer at the company with between one and three years of experience, according to an Axact job advertisement, gets transportation between the office and home (with a daily newspaper), full medical coverage for the employee and the immediate family, 34 days of annual leave and “fixed monthly financial support amounting to 80% of your gross salary” in case of a mishap. In a 2014 speech, Shaikh claimed, this financial support would be paid to a deceased’s family for life.

The salary for this position is between Pakistani Rs. 40,000 ($392) and Rs. 60,000 ($588) a month, about six times the average income in Pakistan.

And there’s more, as per the job advertisement:

We offer a number of exciting facilities such as modern salon, spacious cafeteria, movie theater, indoor games, hut facility, Yacht, Dreamworld club and many more. This was just a gist of the enviable lifestyle at Axact…

Young, educated and well-spoken salespersons are reportedly rigorously trained for up-selling and cold calling.

A job advertisement for Axact’s “International Sales Leadership Program” based in Karachi, for example, sought candidates with ”neutral or non-inflicted American or British accent,” preferably with “experience in handling international clients via telephone, email and live chat.”

How the internet helped

Much of this entire operation, according to the Times, was bankrolled by a massive network of at least 370 websites of schools and accreditation bodies that churned out fake degrees.

Sometimes, as per the Times report, these employees even call prospective clients by posing as recruiters promising to offer a job if they buy an online degree. Many students are duped; many others buy fake degrees voluntarily, with full knowledge of those being unaccredited.

High school diplomas sell for around $350, according to the New York Times, while doctoral degrees cost $4,000 or more.

Shaikh plans to give it away

But Shaikh, who once wanted to become the Bill Gates, now has a new dream: He wants to give it all away and help Pakistan.

Some 65% of Axact’s revenues, he said last year, with be given to SED Axact, a division of the firm that’ll work on making “education, healthcare, judicial assistance, and food and shelter affordable and accessible to all by the year 2019.”

It will begin with educating 30,000 students, and then scale it up to reach a staggering 10 million children. That’s a little less than half the total number of primary-school-age children (21.6 million) in Pakistan.

“I no longer wish to become the wealthiest man in the world,” Shaikh said last year, “Axact and my mission is now to win, and disburse our winnings for the good of the people and the good of our country.”

Update: Shaikh’s total declared income has been updated to reflect the fact that the 5% tax rate is only applicable to income exceeding Pakistani Rs. 400,000.

Madhura Karnik and Shelly Walia contributed to this report.