Eleven months and three and a half weeks of the year, most of us show up to work and try to do our jobs. Some of us do them well, some poorly. Some of us pour our heart and soul in, and some of us are watching the clock from the first cup of coffee.

Whatever way we work, the way that many of us are forced to spend those other few days each year is to undergo a charade. We write out goals and vision statements and self-evaluations, or copy them from an email from HR. Then we sit down with a supervisor who has probably already made up his mind about whether or not we’re getting a raise, or a pink slip.

I’m talking, of course, about the performance review. It’s an arcane system that has little to do with the realities of the modern workplace.

Gone are the days when career advancement only required showing up every day and doing what you are told. Moving forward in today’s knowledge economy requires constant learning of new skills, personal reinvention, and the foresight to stay ahead of the curve. You can’t leave it to your boss to guide you once a year and expect to advance.

The concept of a performance review–objective feedback on whether your efforts are sufficient to keep you both employed and moving forward–is a good one. But the changing economy means the concept is out-of-date and flawed. The labor market has changed–a career-long job where you rise through the ranks is no longer the norm. That’s precisely why you can no longer rely on your employer’s feedback, which is more like a trap designed to keep you in a position where you are most valuable to your employer, rather than most valuable to yourself, on the job market.

Workers today need to undertake their own performance review–and take it to the streets.

Before I explain, let’s convict the existing model. The first witness is UCLA management professor Samuel Culbert, who believes the whole review process is bogus:

“The alleged primary purpose of performance reviews is to enlighten subordinates about what they should be doing better or differently. But I see the primary purpose quite differently. I see it as intimidation aimed at preserving the boss’s authority and power advantage. Such intimidation is unnecessary, though: The boss has the power with or without the performance review.”

He argues performance reviews are both too arbitrary and rigid to offer useful feedback. They may even contribute to an awkward, hostile, work environment. Besides, Culbert thinks modern workers’ skills are too idiosyncratic to be evaluated using traditional metrics or one person’s opinion. That’s never been truer.

Nowadays, being valuable to your employer–and a catch in the labor market–takes a new set of skills. How you are doing in your particular job, while important, is not a sufficient indicator of how your career is progressing. If you want to advance, it’s more important to develop what makes you valuable to your industry (industry-wide capital) rather than just your job.

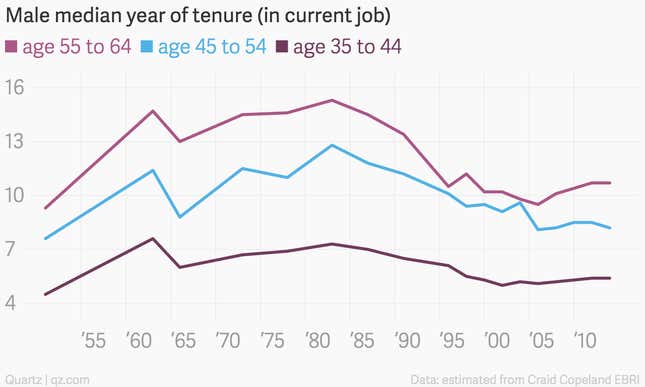

Once upon a time, a person’s career was dominated by a long-term relationship with a single employer. People often tried different jobs when they started out, but many eventually settled into a long-term arrangement that lasted until retirement. Today long-term commitments are less common. The figure shows the median tenure of men (women have longer tenure than before, reflecting their increased labor force participation) by age group:

Men have lower tenure these days because unions are less powerful, but also because greater globalization and new technologies have changed the incentives to both workers and employers. Before, it made more sense for both groups to build up firm-specific capital. (Firm specific capital includes knowing the processes specific to your employer, how to deploy its technology, and the ins-and-outs of its culture.)

Take car manufacturing, which was once a big source of long-term employment. It used to be a car was made differently at GM than it was at Ford. But now manufacturers use more machines, which means the manufacturing process has become more standardized across firms. That, in theory, makes it easier for employees to change jobs, making them and their employers less invested in their relationship. The move to more service jobs has had a similar effect. These jobs reward people who have a large professional network (which means more potential clients and competitor intel) and the ability to anticipate and quickly learn the latest technology.

When there’s a large premium on industry capital, long tenure has less value. Changing jobs exposes you to different technology, how other firms operate and broadens your network. According to Wharton management Professor Peter Cappelli, employers no longer want to spend resources training their employees, yet there’s still an expectation that employees have skilled learned on the job. Cappelli thinks employers demanding skills they are unwilling to teach explains the economy’s so-called skills gap. The gap puts a burden on the modern worker to make sure he’s always learning, and not relying on his boss to train him.

So, the shift from firm to industry capital has made the traditional job review a totally insufficient way to monitor your career progression. There may be some useful insights about your general work habits that can be of help. But performance reviews are structured to gauge your progress in terms of one particular firm’s culture and needs–not your own.

What to do instead? Get your performance review from the outside world. What matters much more than an incremental raise at a job you may not have in three years is to figure out how to position yourself for that next big jump in title, responsibility and pay. And these days, that’s likely to come from another company, not from an internal promotion.

If you want to move your career forward, you should follow up your internal review with an external one. Check in with your contacts to assess the state of the industry and how you measure up to your peers elsewhere. The modern economy demands taking more personal responsibility to keep your skills fresh and relevant, and that means seeking out your own performance review.