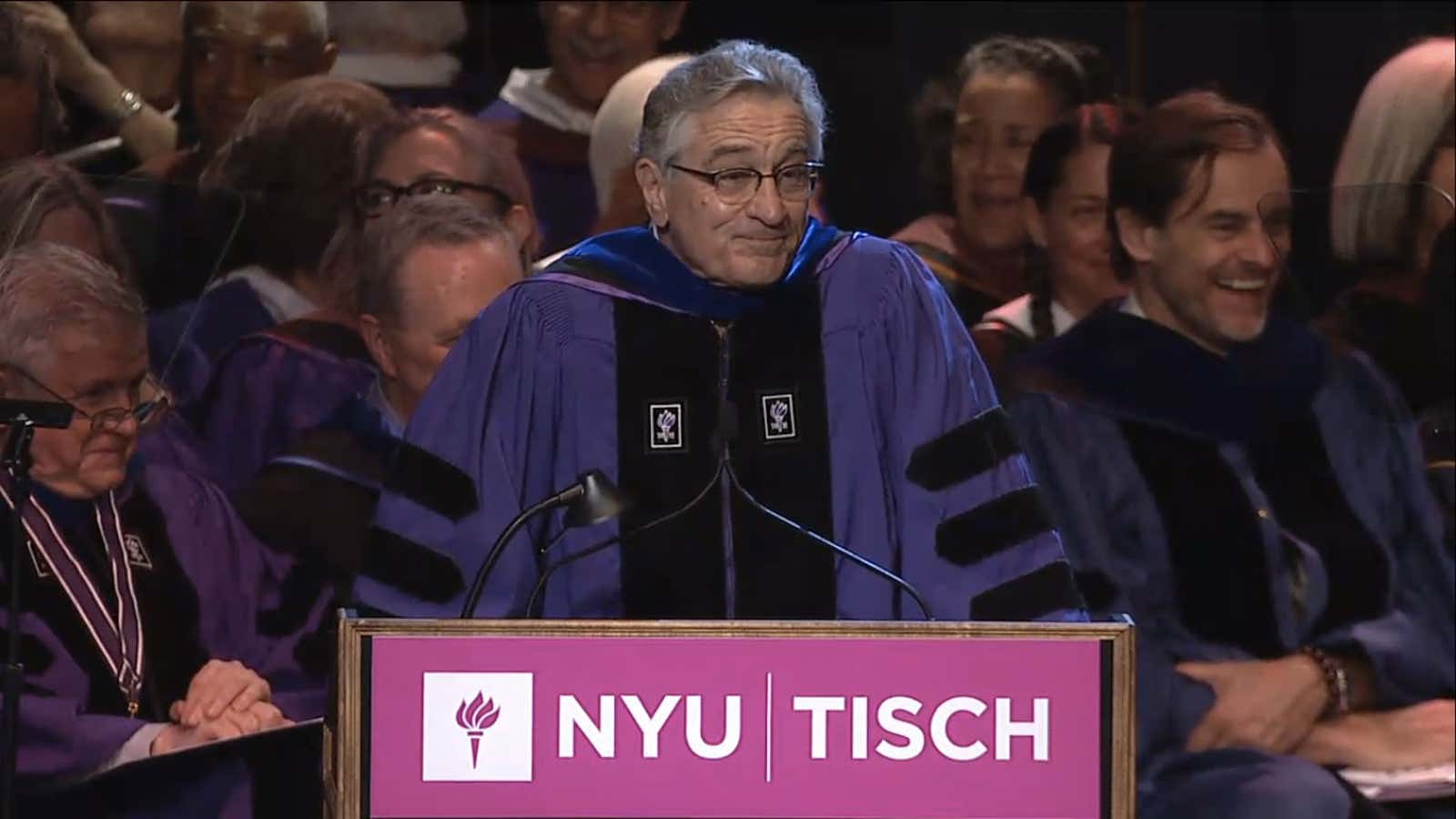

Robert De Niro put it bluntly to the graduating class of New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts: “You’re fucked.”

The actor, director, and producer—whose film credits include Taxi Driver, Goodfellas, The Godfather: Part II, and Bang the Drum Slowly—delivered his commencement speech on Friday (May 22.)

“On this day of triumphantly graduating, a new door is opening for you: a door to a lifetime of rejection,” he said, only partially joking.

Over and over again, De Niro urged the new grads to follow their passions and not get deterred by rejection (emphasis ours).

When it comes to the arts, passion should always trump commonsense. You weren’t just following dreams, you were reaching for your destiny. You’re a dancer, a singer, a choreographer, musician, a filmmaker, a writer, a photographer, a director, a producer, an actor, an artist. Yeah, you’re fucked.

The good news is that’s not a bad place to start. Now that you’ve made your choice or rather succumbed to it, your path is clear, not easy but clear. You have to keep working. It’s that simple. You got through Tisch, that’s a big deal. Or put it another way: You got through Tisch, big deal. Well, it’s a start.

On this day of triumphantly graduating, a new door is opening for you: a door to a lifetime of rejection. It’s inevitable. It’s what graduates call the real world. You’ll experience it auditioning for a part or a place in a company. It’ll happen to you when you’re looking for backers for a project. You’ll feel it when doors close on you while you’re trying to get attention for something you’ve written or when you’re looking for a directing or choreography job.

How do I cope with it? I hear that Valium and Vicodin work. Eh, I don’t know. You can’t be too relaxed and do what we do, and you don’t want to block the pain too much. Without the pain, what will we talk about? Though I would make an exception for having a couple of drinks if hypothetically you had to speak to a thousand graduates and their families at a commencement ceremony. Excuse me. [He jokingly ducks under lectern.]

But he warned that they shouldn’t take rejection personally, even using a humorous example of him trying out for the role of Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma.

Rejection might sting but my feeling is that often it has very little to do with you. When you’re auditioning or pitching, the director or producer or investor may have something or someone different in mind. That’s just how it is.

That happened to me for the role of Martin Luther King in Selma, which was too bad because I could’ve played the hell out of that part. I felt it was written for me. But the director had something different in mind, and you know, she was right. It seems the director is always right. Don’t get me wrong. David Oyelowo was great. I don’t think I would’ve cast a Brit.

I’ve got two more stories—these really happened. I read for Bang a Drum Slowly seven times. The first two of the three times I read for the role of Henry Wiggen, the part eventually played by Michael Moriarty. I read for the director. I read for the producer. Then they had me back to read for another part, the role of Bruce Pearson. I read for the director. I read for the producer. I read for the producer and his wife. I read for all of them together. It was almost like as long as I kept auditioning, they would have time to find someone they liked more. I don’t know exactly what they were looking for, but I’m glad I was there when they didn’t find it.

Another time I was auditioning for a play. They kept having me back. I was pretty sure I had the part, and then they went with the name. I hated losing the job, but I understood. I could’ve just as easily lost the job to another no-name actor, and I also would’ve understood. It’s just not personal. It could really be nothing more than the director having a different type in mind. You’ll get a lot of direction in your career, some of it from directors, some from studio heads, some from money people, some from writers, though usually they’ll try to keep the writers from a distance, and some from your fellow artists. I love writers by the way. I keep them on the set all the time. Listen to all of it, and listen to yourself.

De Niro also decided to repurpose the advice he’s given his own children (go into accounting):

While preparing for my role today, I asked a few Tisch students for suggestions for this speech. The first thing they said is, “Keep it short,” and they said, “It’s OK to give a little advice, it’s kind of expected, and no one will mind.” And then they said to keep it short.

It’s difficult for me to come with advice for you who have already set upon your life’s work, but I can tell you some other things I tell my own children. First, whatever you do, don’t go to Tisch School of the Arts. Get an accounting degree instead.

Then I contradict myself, and as corny as it sounds, I tell them don’t be afraid to fail. I urge them to take chances, to keep an open mind, to welcome new experiences and new ideas. I tell them that if you don’t go, you’ll never know. You just have to be bold and go out there and take your chances. I tell them that if they go into the arts, I hope they find a nurturing and challenging community of likeminded individuals, a place like Tisch.

If they find themselves with a talent and a burning desire to be in the performing arts, I tell them when you collaborate, you try to make everything better, but you’re not responsible for the entire project, only your part in it. You’ll find yourself in movies or dance pieces or plays or concerts that turn out in the eyes of critics and audiences to be bad, but that’s not on you because you will put everything into everything you do. You won’t judge the characters you play, and you shouldn’t be distracted by judgments on the works you’re in. Whether you work for Ed Wood, Federico Fellini, or Martin Scorsese, your commitment and your process will be the same.

By the way, there will be times when your best isn’t your good enough. There can be many reasons for this, but as long as you give your best you’ll be OK.