For more than a decade, China’s taken a verbal beating from other countries for keeping its currency unfairly cheap. Those days might finally be over. The yuan (a.k.a. the renminbi) is no longer undervalued, the International Monetary Fund’s Markus Rodlauer said earlier today, while also urging Chinese leaders to allow the currency to trade more freely.

The US government, however, disagrees. Last week, Jacob Lew, the treasury secretary, held firm on his department’s long-standing contention that China continues to repress the yuan’s value.

The IMF’s about-face could boost the Chinese government’s push for broader usage of its currency outside China, particularly as a reserve currency for central banks. Rodlauer said the IMF supports Chinese authorities in the next step of that effort, the yuan’s inclusion in the IMF’s basket of reserve currencies, which the IMF is reviewing in October.

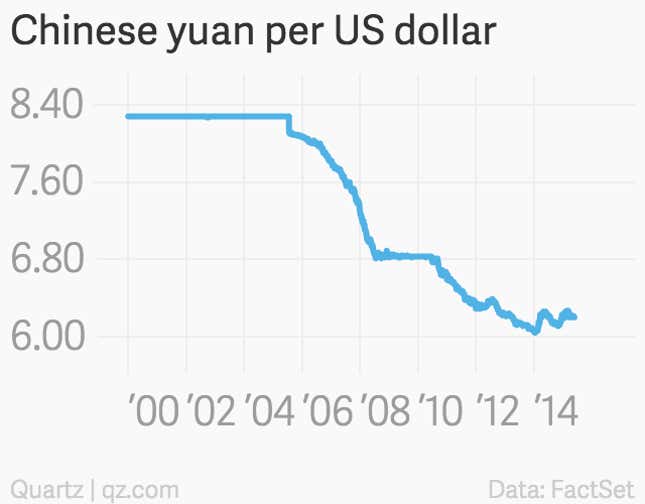

In the past, the Chinese government set the exchange rate artificially low, making its exports cheaper than those of other countries. That caused its trade surplus to balloon—and with it, the US’s trade deficit. Under pressure from the US government, the Chinese government let the yuan appreciate around 30% since 2005.

Today, the Chinese government still sets the daily exchange rate, allowing the yuan to trade in a fixed band to either side of that value. Though it widened that band slightly a year ago, the central banks intervenes on occasion to control the currency—something the US government calls “manipulation.”

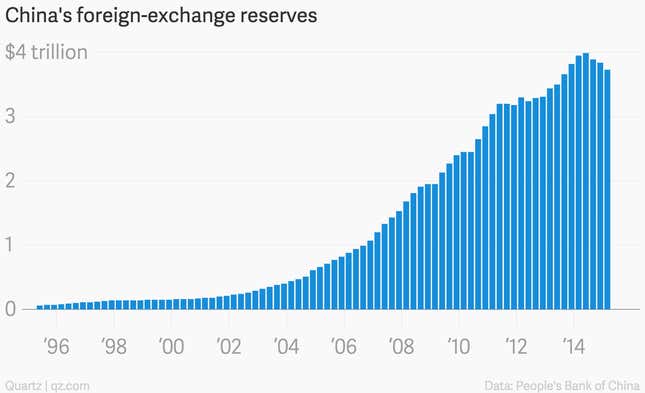

But the IMF seems a little more hip to new trends than the US government. Since 2015, the People’s Bank of China, the central bank, hasn’t been keeping the currency cheap. Rather, it’s been defending the yuan, drawing down its foreign-exchange reserves in order to keep the value aloft.

Why would it do that, knowing that might hurt the export sector, which provides a huge share of jobs? In the last few years, demand for the yuan has come less and less from trade, and more from investment flowing into China to speculate on the currency’s appreciation against the dollar—a self-reinforcing phenomenon. Those inflows help prevent cash squeezes in the banking system, and push down borrowing costs. Letting the yuan’s value drop might drive that investment out of China, draining cash from the financial system dangerously fast.

Keeping the yuan from falling will also help global capital to China’s stock and bond markets, staving off the corporate sector’s enormous debt woes. Plus, as Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University, recently noted, manufacturing-sector unemployment isn’t the primary worry for the economy these days. In fact, by boosting wages, a cheaper yuan would hurt services—a sector whose growth is crucial to China’s plans for rebalancing.

But China still has a ways to go if it’s going to make the IMF’s reserve currency basket. If China wants the yuan to become a global reserve currency, it likely must let the yuan trade freely and stop controlling the flow of money in and out of the country.