On May 20 in a courtroom in South Africa’s North West province, a judge sentenced Pule Stoffel Botlhokwane to two life terms for killing Gift Makau last August. Makau, a 23-year-old lesbian, had been raped and strangled, with a hose shoved into her mouth.

A photograph of Makau’s identity document, stamped “DECEASED,” fills a wall that visitors encounter upon entering “Isibonelo/Evidence,” an exhibition of 87 photos by Zanele Muholi on display through Nov. 1 at the Brooklyn Museum in New York.

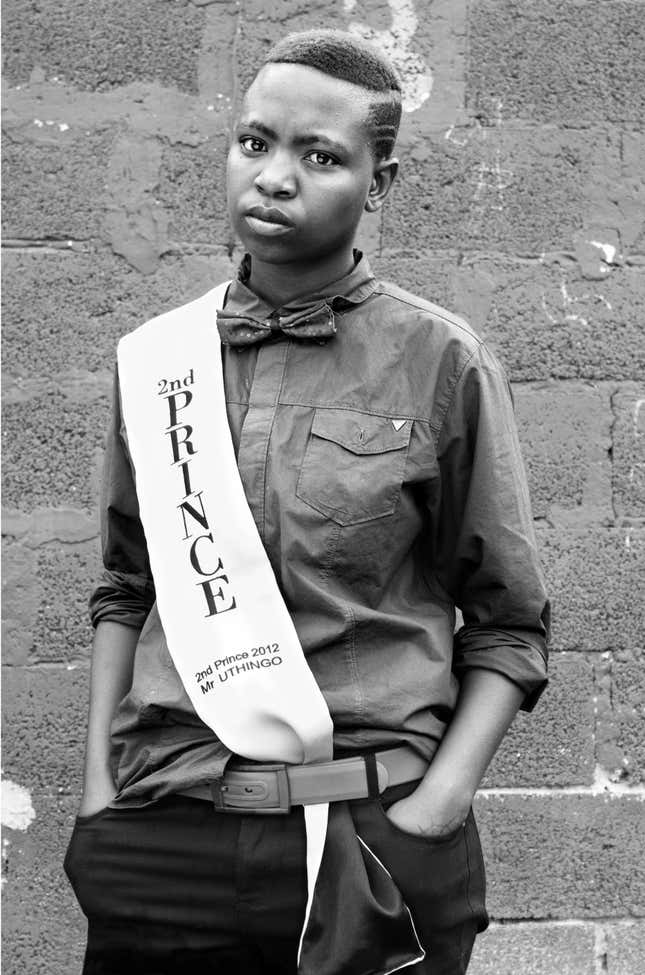

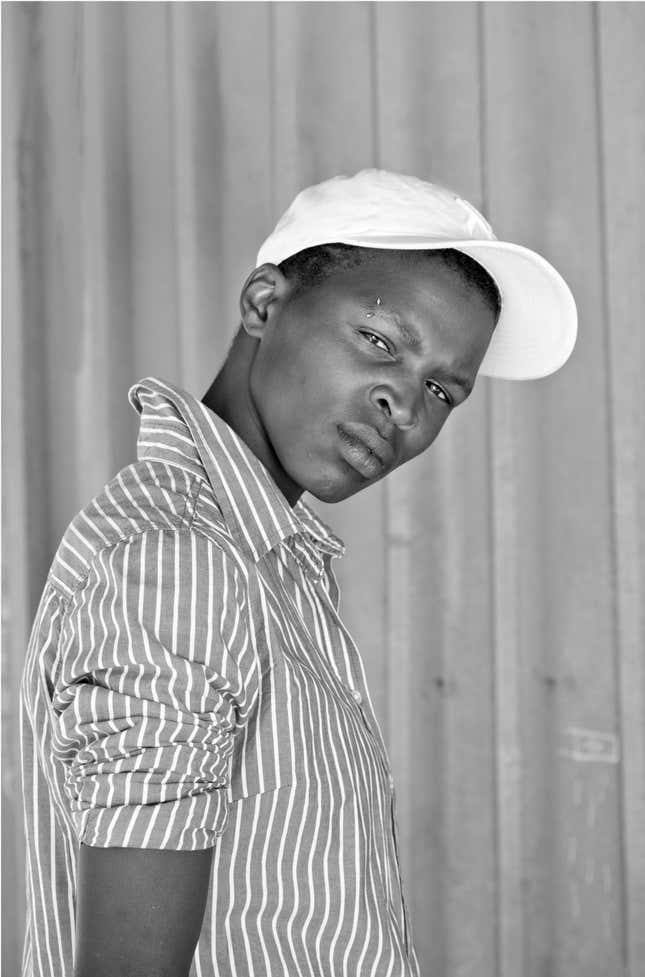

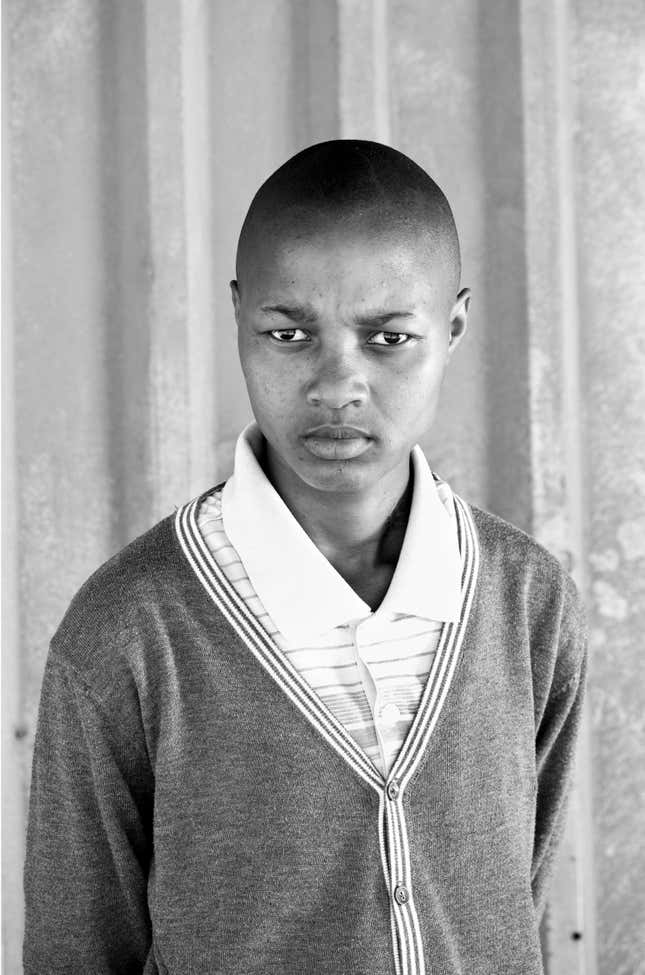

The show opens with 60 black-and-white portraits from which gaze lesbian, gay bisexual and transgender (LGBT) South Africans. Since 2006, Muholi, 42, has documented fellow members of the LGBT community as part of a series titled “Faces and Phases,” which aims to challenge homophobia and transphobia by recording black South Africa’s queer culture and visual history.

The exhibition also reveals the work of Muholi and others to chronicle an epidemic of violence directed toward South Africa’s black LGBT population despite the republic’s being the first country on the continent to recognize same-sex marriage. The violence sparked by anti-gay attitudes reared again last Saturday, when Ibanathi Ngcobo, a 23-year-old Durban man, was assaulted by two men outside a nightclub in the city allegedly for no reason besides being gay.

“We have had the wrong perception that it’s un-African to be homosexual, or it’s un-African to be trans,” says Muholi, who terms herself a “visual activist” and was short-listed for this year’s Deutsche Börse Photography Prize. Her photos, she adds, make “it even easier for people who have been persecuted to see they are not alone, that there are many of us.”

The images achieve that intent through their insistence on the individuality of their subjects. “It’s important that we name the participants in our projects because naming is a political statement on its own,” she tells Quartz. “We are connected by our identities.”

Muholi grew up in Umlazi, a township south of Durban, and later studied at the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. In 2009 she founded “Inkanyiso,” a collective that encourages black LGBT Africans to share stories of their lives.

At the gallery in Brooklyn, a slew of accounts fill a chalkboard that rises amid the portraits. There survivors of “corrective rape” and sexual violence describe assaults at the hands of relatives, coaches and neighbors. “They tell me that they will kill me, that they will rape me, and after raping me I will become a girl,” reads one account. “I will become a straight girl.”

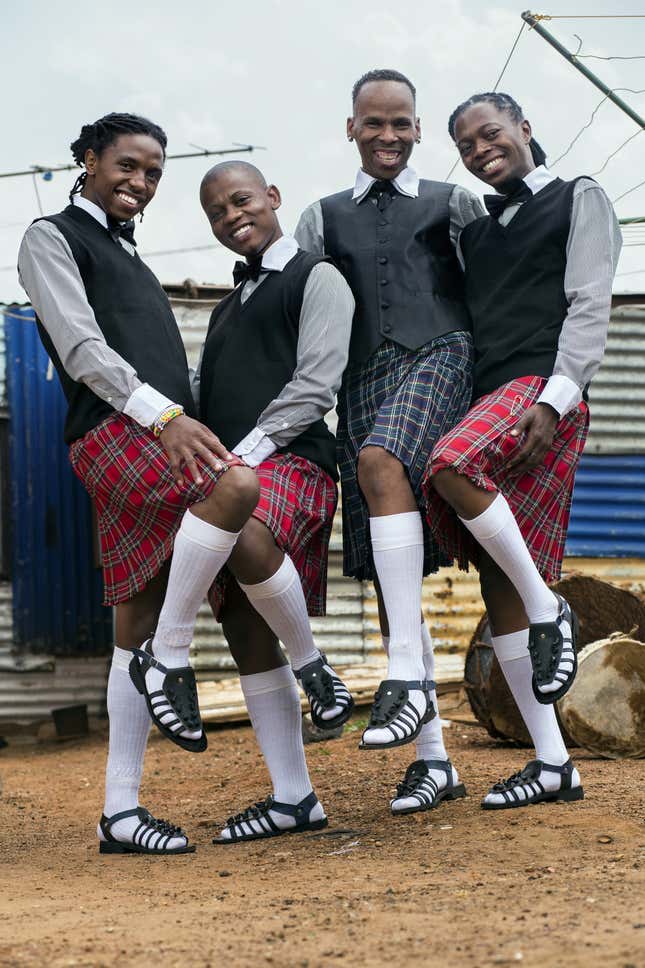

In an adjacent gallery, 27 photographs that burst with color show same-sex LGBT weddings. Muholi describes the juxtaposition as a way to depict the fusion between love and loss that marks the lives of South Africa’s LGBT community.

The histories of LGBT people in their countries of origin was ongoing but rarely documented, observes Muholi, who explains that her work counters portrayals that dehumanize black lesbians and trans people.

“We’re challenging the status quo,” says Muholi. “It’s my wish that we have these kinds of visual materials so that generations to come can learn early that homosexuality, transgenderism and queerness are part of our lives.”