Until now, mining good journalism from the web’s depths has been done from the top. Over the last 13 years, looking for “signals” that flag quality content has been at the core of Google News: With a search engine scanning and ranking 50,000 sources in 30 languages and 72 editions, its inventor, the famous computer Scientist Krishna Bharat, has taken his extraordinary breakthrough to an immense scale.

The whole system is build on a series of metrics that qualify contents: see Google News: The Secret Sauce, and the most recent version of Google News’ patent. More recently, Google News chief Richard Gingras and Sally Lehrman came up with a manifesto titled the Trust Project (read the latest version on Medium), aimed at the same goal. Lehrman (a Senior Fellow in journalism ethics at Santa Clara University) and Gingras are working on another set of “signals” aimed at pinpointing quality journalism mostly based on disclosure and methodology expressed by the news source (I discussed the matter here).

The two approaches are complementary: the traditional Google way—automated, algorithmic, scalable up to the extreme—and the manual way in which a news organization will deliberately state its own quality attributes. As Gingras puts it, the huge challenge in defining quality in digital journalism is to make it bothhuman-readable and machine-readable, and I will add, as foolproof and cheat-proof as possible.

Before we go further, let’s discuss what defines, from a reader’s perspective, quality journalism. Here is a possible list of subjective attributes, in alphabetic order for lack of a smarter classification), that a good piece of journalism should feature:

– Authoritative: This is a complex notion as “authority” comes in many forms. One sure thing: authority no longer boils down to a great author writing for a big news organization. Authority can come from a single writer working in a one-person business (ranging from Ken Doctor to Ben Thompson), or from a large corporation such as Google (when Gingras writes about the news business, people listen), or VC firm with in-house pundits such as Benedict Evans (Andreessen Horowitz) or Mary Meeker (Kleiner Perkins).

– Agenda-setting: The usual definition refers to the “news media’s salience and its ability to influence the public agenda”, even though this meaning has been weakened by the rise of social media which are seen as offering a quantitative measurement of a topic’s “importance”.

– Contextualized, Comprehensive: The good story provides depth, perspective and meaning.

– Definitive: That’s probably the rarest quality of great journalistic material — and the most subjective one. It occurs when reading someone’s profile or reporting, the idea emerges that the writer has left very few other avenues to explore, no stone is left unturned.

– Embodied: The best stories are often built around well-defined characters. A cold narrative is not enough.

– Factual: The more facts, the better. The denser, even better. This feature is the most spontaneously singled-out by readers who increasingly reject fluff.

– Forward-looking: All reader surveys converge on one element: readers need bearings; they enjoy to be shown why the story’s subject matters and how it could influence their lives.

– Quoted, Linked, Referenced, Sourced: That’s the Jeff Jarvis part: Link to whatever you need, profusely so. The concept has its limitations, but good linkage practices favor both depth and compactness.

This list is by no means exhaustive. Depending on the type of story, many other criteria can apply.

Today, most efforts to surface quality focus on an ex-post analysis of these attributes. That’s how Google News works, and to some extent, what Search Engine Optimization is build upon. This approach is no longer sufficient. Especially when Google News people admit that they are still struggling to properly extract an item as simple as an article’s byline because every publisher has its own way of handling story authorship.

Some of these criteria are subjective and require human interpretation (for instance the forward-looking aspect of a story); but others can be extracted and tagged automatically during the production process.

Hence the question: Why not invert the process and have the CMS tag all the quality attributes just mentioned? Let me take the example of this recent New Yorker story about Marc Andreessen and the venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

This piece, written by Tad Friend and titled Tomorrow’s Advance Man, runs a lengthy 14,000 words.

Published on May 18th, it still ranks high in Google Search (fourth position after ten days). It’s because it checks all the boxes (for instance, the New Yorker scores high in Google’s unofficial Quality index.) But, within a few months, no doubt this great story — quite enlightening about venture capital mores — will be buried under many layers of more recent stuff perfectly suited to the SEO grammar.

Here is how a CMS can help. Produced by an industrial-grade editorial system, this story can natively state and include many attributes expressing its journalistic quality. And if the search engine is properly configured to capture these quality signals, the story might rise naturally above the background noise.

The circuit could go like this:

Let’s look at examples.

Length: I’ve always been bewildered by Google’s inability to retrieve a story on the basis on its number of words. That’s unfortunate because story length is the primary signal to in-depth reporting. (Actually, this feature alone could be great for news outlets such as Business Insider of BuzzFeed known to produce short stuff but that sometimes decide to publish long pieces.) Evidently, any CMS can store length information inside an article’s metatag container.

The CMS can also “broadcast” many valuable items pertaining to the quality, breadth and depth of a piece such as the number of named entities (people’s names, places). Here is how the New Yorker piece about Marc Andreessen renders through IBM’s AlchemyAPI filter:

Starting from this, plenty of extractions can be dynamically performed, such as the ratio between named entities and concepts: a piece with only a few concepts associated to lots of named entities is likely to dive deep into its subject, while an article covering many concepts with few named entities is deemed superficial. This technique can be used to define the type of article.

The CMS also provides clues about who contributed to the stories, not just direct authors, but also anyone who touched it (editors, copy editors, fact checkers); this signals the level of editorial care.

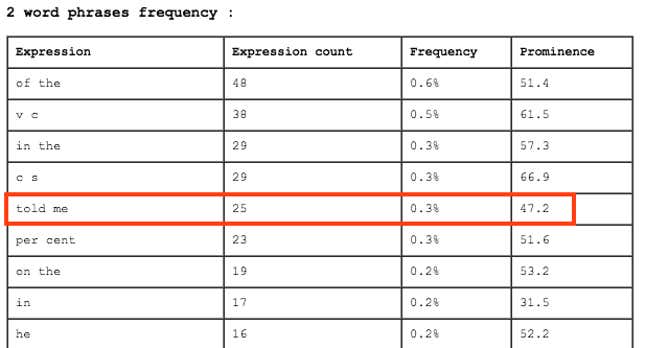

As for quotes (“….”) often associated to first-hand sourcing (there are more than 200 in the Andreessen story), the use of such marks should trigger the injection of a machine-readable tag that will signal the existence of third party verbatim. Even better, a simple semantic analysis can spot typical phrase used by writers to emphasize their proximity to the subject, such as the “XYZ told me”… It was used with great prominence in the New Yorker piece I parsed through the Textalyseranalytic software:

Technically speaking, building the foundation of such a system is not overly complicated. But its deployment requires collaboration as the CMS needs to “broadcast” a syntax that will be understood by the search side.

From this, you see where I’m going. There is only one company with the reach and technical ability to develop and spread the required standard—which needs not be an open one, definitely not proprietary.

This company is Google. The internet giant could easily build a CMS, along with the semantic standards required to seamlessly connect editorial production to search, not just Google-powered search, but also to all services interested in extracting editorial value from the web. Such move would undoubtedly benefit Google (who could embed its DFP ad server and even its YouTube player in the system), and it would also serve the entire digital news sector by raising the value associated to the most expensive part of its production.

Google has a short window of opportunity to do so as the vast majority of publishers are working on their own CMS. Publishers do so reluctantly as no one is overjoyed at building the equivalent of printing presses, ink, or plates for the digital world.