Stanford University’s Alvin Roth is a very rare thing: An economist who saves lives.

The co-recipient of the 2012 economics Nobel got his prize, in part, for helping to fix a long-standing problem with the market for kidney donations. Often family and friends were willing donors for someone who needed a kidney. But for medical reasons they weren’t a compatible match.

Building on previous work in which he had reshaped the National Resident Matching Program, which matches medical-school graduates with hospital internships, Roth devised an algorithm that would help match willing kidney donors to compatible recipients with whom they had no other connection.

That system became the cornerstone of one of the country’s first kidney exchange clearinghouses. Roth estimates his work has resulted in roughly 4,000 kidney transplants that might never had happened if not for the system he worked to build.

The market for donated kidneys is an example of what economists call a “matching market.” These markets govern everything from corporate hiring decisions to how we meet spouses, but they obey laws more complex than the simple balancing of supply and demand with prices.

While Roth’s early research focused on somewhat abstract areas of economics including game theory, over time he has transformed himself into something of a matching market guru.

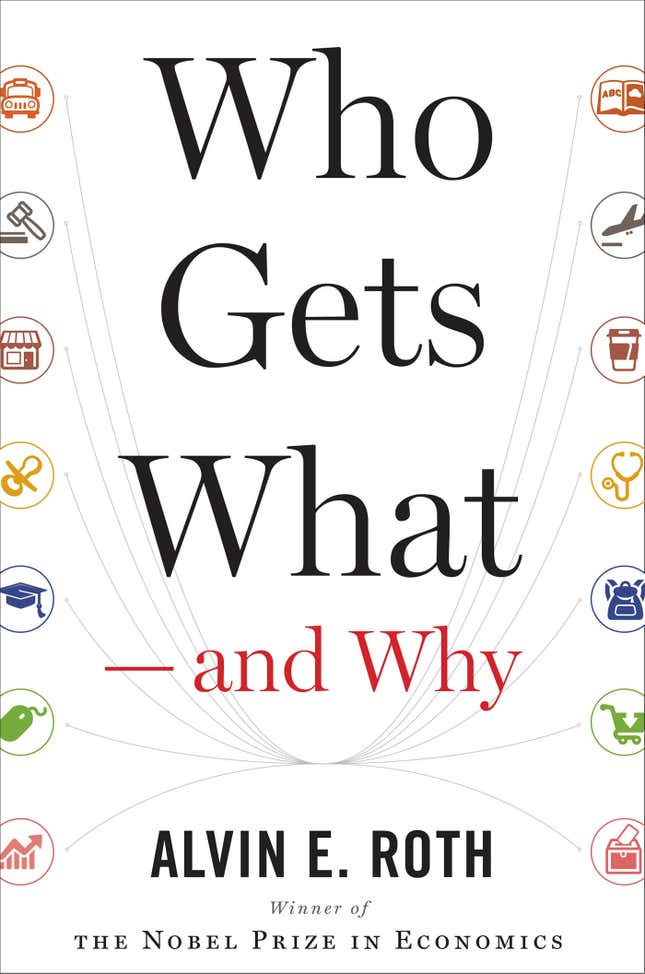

Roth swung by Quartz’s New York offices recently to chat about his new book, Who Gets What—and Why, which explains how matching markets work, why almost everyone makes it illegal to buy kidneys, and why it’s increasingly rare for people to marry their high-school sweethearts. Here are edited excerpts of our conversation.

Quartz: One of the ways we usually think about markets is in terms of the market for, say, crude oil or Apple stock. But you deal with “matching markets.” Can you briefly explain what those are?

Alvin Roth: Once you start looking at marketplaces one of the things you notice is that not all marketplaces are set up so that their job is merely to find a price at which supply equals demand. Those are the commodity markets. But lots of markets, even when they have prices as very important parts of the market, don’t set the price so that supply equals demand.

Labor markets don’t do that. Quartz doesn’t hire people by lowering the wage until [only] just enough people want to come work here. Instead, presumably you get to interview bunches of people who would like to work here and you get to hire some of them. But you have to compete.

The name of the book is Who Gets What—and Why. After reading it, I thought you could have added “and When” to the title. There’s this timing component of markets that’s really fascinating. You spend a lot of time on it.

Lots of markets clear very early—before lots of information is available. Book publishing is a good example. Publishers buy books before the books are written and they don’t really know what they’re getting.

If you’re graduating from law school, you get hired long before you graduate. Before firms really know what they’re getting. Before you might know what kind of law you really want to do.

Doctors used to be hired two years before graduation and that’s eventually one of the things that eventually led to the centralized clearinghouse for doctors [in the US], the National Resident Matching Program.

Another example of timing that you deal with in the book is high-frequency trading.

A guy who is doing really interesting work on financial markets is Eric Budish at the University of Chicago. What he’s been looking at, among other things, is the the thickness of the market in minutes and seconds, and then in microseconds. You can have some heavily traded securities, like S&P 500 indices, that are really traded lots and lots. But when you look at the microsecond level, many microseconds can go by with no trades.

So a market that is really thick on a human scale becomes very thin when you look at microseconds. What he’s found there is that some of this high-speed trading is causing competition on price to be replaced with competition on speed. And that interacts with how the market is designed, and [it] might be redesigned to remove some of the disadvantages of high-speed algorithmic trading.

You sound very excited in some parts of the book with some of the opportunities out there. [Editor’s note: Stanford University is in the heart of Silicon Valley.] For instance, some of the billion-dollar unicorn start-ups, such as Airbnb and Uber. We usually describe them as companies but you describe them as marketplaces.

Absolutely. Airbnb is a matching market between travelers and hosts. Uber is a matching market between travelers and drivers.

It seems like a boom time at least for these kinds of markets. Why now?

Well some of the reasons are technological. It’s hard to think of eBay before the internet. It’s hard to think of Uber before the smartphone. With smartphones you carry a marketplace in your pocket, so you have more access than ever to marketplaces. I think that’s a big part of the reason.

You started in a sort-of arcane area of economics, game theory. But it seems that early on you also start looking for opportunities to put these ideas into practice. You seem really interested in finding ways to help people. And I’m wondering if you think that should be the goal of economics? And, if so, what are the value of abstract models?

Abstract models are very, very useful for organizing your thoughts and learning some things that you can’t learn without them. So I wouldn’t want to say that the goal of economics should be building concrete [things] in the world. But that should certainly be one of the goals.

Think about biology, broadly, with medicine as one part. Not all biologists should be doctors. But it is important to have doctors too.

And it’s important to have medicine that learns from biology. And you want biology and medicine to work together so that abstract, abstruse concerns with things like genes and DNA and proteins should eventually be translated into medical care and better health.

Where does the kidney exchange project stand right now? It’s been hugely successful in many ways. But there’s still a big need for kidneys in the US and around the world.

Kidney exchange has been a big success. I can talk to you about about victory after victory. But it’s in a war that we’re losing.

There are 100,000 people waiting for kidneys in the United States right now. And we only do about 17,000 transplants a year. So we have a big shortage of kidneys.

When economists see big queues forming, they worry that prices aren’t adjusting normally. And the law of the land is that the price of a kidney has to be zero.

Kidneys have to be gifts. And the striking, unusual thing about that law is that it’s the law just about everywhere in the world except Iran… When you see something that’s against the law everywhere in the world, at least, it makes me suspect that there’s something we don’t understand.

Approaching this problem is going to be something different than explaining slower and louder and simpler that transactions between consenting adults improve welfare on both sides. And if they don’t harm other people they should be allowed.

But that’s why kidney exchange is so useful. You can bring some of the benefits of welfare-improving transactions without violating the law.

But we’re not getting enough kidneys that way. So there’s increasing interest and consensus in removing the financial disincentives for donating a kidney.

If you wanted to give me a kidney, it’d probably cost you some money. I live in California so you’d have to fly to California. You have to take off work. You would need a hotel for a couple of days before and maybe a few days after. So you could run up bills of several thousand dollars along with taking off work. I think there’s increasing agreement that that shouldn’t have to be.

But there’s not yet agreement on going forward partly because there’s so much fighting about whether we should be trying to repeal the National Organ Transplant Act (pdf) or whether we should be trying to do something else.

So I would like to see some organized effort in that direction, which would also give us some information about the elasticity of supply.

Paying people for their organs falls under this element of markets that you describe as “repugnant transactions.”

I got into this by trying to understand why it’s against the law everywhere to buy and sell kidneys. When you start to look at it you realize that there are a lot of things that it’s against the law to buy and sell.

So what I call a “repugnant transaction” is a transaction some people would like to engage in but other people don’t want them to, even though they don’t personally come to any harm from the transaction. And when you start looking around with those glasses on you see quite a few.

One that is dramatically changing in our time is same-sex marriage. There’s a prototypical “repugnant transaction” because some people would like to do it and other people don’t want them to, and this is an issue that has divided Americans quite a bit.

But in the last 10, 11 years we’ve seen a sea change. It started in Massachusetts in 2004. And maybe the Supreme Court will decide this year that same-sex marriage has to be legal in all the states.

So repugnant transactions can change. For example, hundreds of years ago, in the Middle Ages, you couldn’t charge interest on loans. Well, we could hardly have the global capitalist economy we have today if you didn’t have a market for capital.

But it’s not just that. As we get more modern, old repugnances fall away. We also develop new repugnances. We used to have markets for slaves in the United States. The most common way to buy passage across the Atlantic Ocean used to be indentured servitude. You would sign a contract that would voluntarily commit you to be a slave for years. So there are things that used to be okay that are now not so okay.

You talk a lot about courtship, romance, marriage—matches like that. Are you familiar with Tinder? And in terms of the ease of finding new matches, is there any potential disincentive to long-term matches if it gets easier and easier to simply find new partners?

So there might be; legalizing divorce presumably made it easier to have shorter relationships and to get out of unhappy marriages.

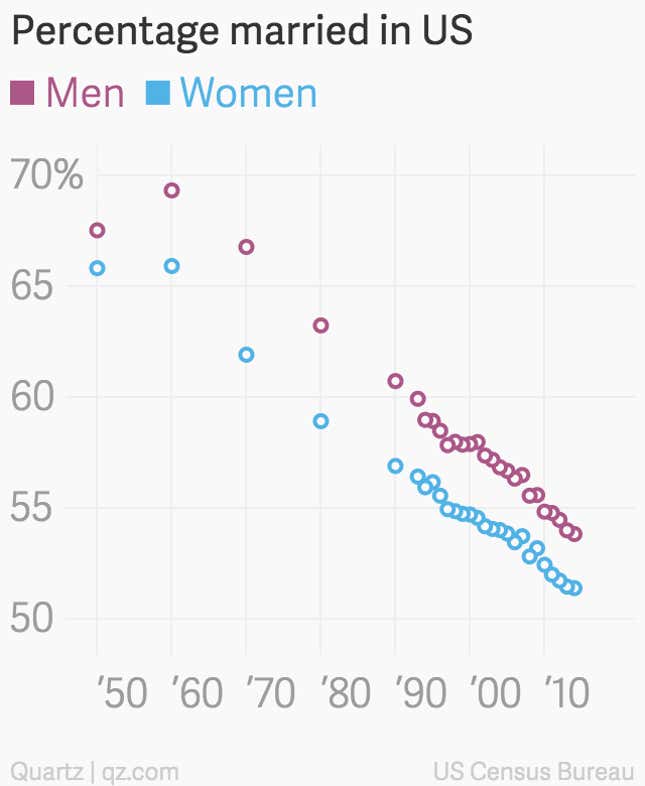

Changing the thickness of markets has over time changed the average age of marriage… When very few women went to college there was a good reason to marry your high-school sweetheart. That was the thick part of the romantic market, when a lot of people your age were marriageable and not yet married.

Then, as the higher education rate for women went up, you didn’t have to marry your high-school sweetheart. There were other opportunities, other sweethearts.

And of course, as women’s participation in the labor force has grown, workplaces have become places to meet each other. But workplaces are tough because you might not want to date the person at the next desk.

So some of the dating sites, like Tinder, have responded to that. But before Tinder think about speed dating, which has a similar design. You meet a bunch of people very quickly, you indicate who you’re interested in, and only if there’s mutual interest do you get each other’s contact information. It was a pre-internet market design of the same sort.

One of the power tips I found in this book was a little tip that might help you get into the college of your dreams: Sign the guest book.

So college admissions is a matching market. You can’t just go to Stanford. You have to be admitted.

Stanford is a pretty fancy university. So my guess is our admissions office doesn’t worry a whole lot about how interested you are. They presume you might be interested in Stanford. But lots of places have to sort among many, many applicants. And… it’s costly to have too few or too many students. So it’s important to them to guess not just how much they like you, but how much you like them, in order to identify students who will come.

But at the same time it’s gotten easier and easier to make applications. If you put in your application through the Common App it’s easy to add one more application. Back in the days when you had to handwrite an essay for each college that you had applied to, [that application] already contained the information that you were pretty interested. That information has been somewhat diluted by making the market thicker, by making it easier to make lots of applications.

There are lots of things at play but part of admissions, part of courtship of all sorts in matching markets, is not just indicating that people should be interested in you, but that you are interested in them. Think about courting a spouse. You want to show that you’re a marriageable guy. But you also want to show that you’re interested, so that attention spent on you is not going to be wasted.

[So] if you come to campus, show that you came to campus. Because you can apply to two dozen colleges but you probably can’t visit two dozen colleges.

Do you know that admissions officers actually look at those guest books?

Oh absolutely. They look at all sorts of things. They track the email traffic. They ask you where else you’re applying. They look at where your parents went to school. They look at a lot of things to try to figure out whether you’re a particularly interested prospect, or just a wheel-kicker.

What are you working on now?

I’m a recovering Nobel Prize winner. In 2012, I spent a year going around talking about work I had done in the past. So now, fortunately, I have some work I’m doing on kidneys, on schools, on repugnance. So now I’m very happy to be back to being a working economist again.

I was listening to Lars Peter Hansen speak and he said after he won the Nobel Prize people who had found him really boring at parties, all of a sudden seemed to think he was the most interesting guy.

They think he’s the most interesting guy, but they also think he knows the answer to every question. And some Nobel prize winners do. But that hasn’t happened to me.