We’ve been hearing about “wearable computing” for years. But we’re finally at a tipping point. Better batteries, miniaturization, and radical new approaches to manufacturing electronic circuits have finally made screens, computers and sensors small enough to stick just about anywhere. It no longer seems strange to see someone wearing a bracelet that records their vital signs, a watch with as much power as a cell phone, or, soon to be available, glasses that augment our reality.

Smartphones are the key to this trend. Now that we’re all carrying powerful general-purpose computers on our person, which are in easy radio range of whatever other devices we might carry, we’re creating our own personal, local cloud-computing networks. Our phones are like brains, and everything from our wireless headsets to our heart-rate monitors are their distributed nervous system.

It sounds crazy, but the cyborgification of humanity is proceeding apace. It will change how we live and how we work, and for the same reason that none of us can put down our mobile devices, we will be powerless to resist.

This year’s Consumer Electronics Show (CES) is flush with so-called “smart watches,” but other kinds of wearable computer that you’ve probably never heard of are also about to take off. Here’s a brief tour through the Internet of You.

On your finger

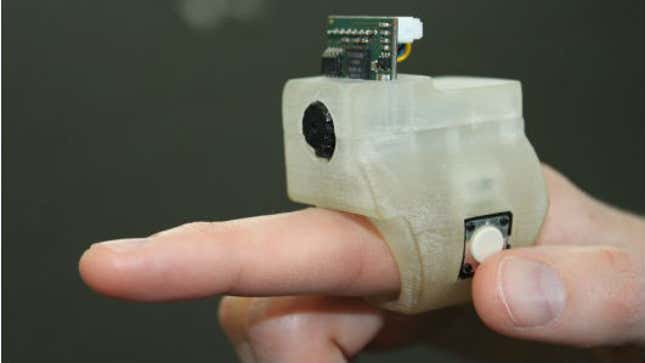

EyeRing

The EyeRing, created by Pattie Maes’ fluid interfaces group at the MIT Media lab, recognizes objects and then announces, out loud, what they are. This handy if you’re blind, but what’s the application for the sighted? Setting aside the fact that many revolutionary technologies begin life as assistive devices—a classical example is optical character recognition, which began in part as a way to help the blind read books—one way it’s already been tested is in the education of young children. Pre-literate kids can point the EyeRing at text and it will read the book aloud.

The EyeRing above is a prototype; hence the bulky plastic housing, which was 3D printed, naturally. But imagine that it shrinks to the size of a regular ring, gains a few more capabilities, and becomes an intuitive and unobtrusive way to translate text for the traveler, accelerate children’s learning, or take over some of the tasks of wearable activity monitors and smart watches.

In your face

Vuzix M100, Google Glass

It seems inevitable that our interface with the internet will always strive to be as intimate as possible. Short of brain surgery, right now that means permanently affixing it to our field of view. Glasses with built-in displays that show us information without hindering our sight are what Google has in mind with its project Glass, which was one of Quartz’s five most disruptive technologies of 2012.

If it Google Glass succeeds, it will be, like the iPhone, a category-defining device that spawns countless imitators. One of those might launch even before Google’s effort does. The Vuzix M100 runs Android, the same OS as countless smartphones, and like Google Glass, already has its own developer program, so that coders can build apps that show you only the information we need, when you need it.

On your wrist

Wrists are such an obvious place to put things that I predict we’ll soon be seeing technology executives so blinged out with wrist-based sensors and interfaces that they start to look like Datta Phuge, the Indian businessman who just bought an all-gold shirt.

Activity monitors: Jawbone Up, Fitbit Flex, Nike FuelBand

Jawbone’s Up is one of the original activity monitors, which track everything from how much you exercise to how well you sleep. Fitbit’s new Flex does the same thing, but is in continuous communication with your smartphone. Nike’s Fuelband incorporates a display, so that you can be constantly reminded how you’re failing to live up to your New Year’s resolution. Not everyone needs an activity monitor, but they’re a good example of how lightweight, unobtrusive devices that are “merely” sensors can wirelessly network with a smartphone in order to enhance its capabilities.

Watches: Pebble, Cookoo, Leikr, MioACTV, CST-01

Most of the excitement about the many, many smart watches announced at this year’s CES has been a result of the long-awaited Pebble. So far, it appears the watch deserves all the anticipation: it’s unique in its capabilities, and represents the first draft of a future in which our phones might just take up residence on our wrists. The Pebble has an e-paper display that is black and white only, but sips power so that the watch can go a couple of weeks between charges.

Pebble is really a little computer, complete with its own apps and community of developers who write them, just like the iPhone and Android. At this point, Pebble’s functions are pretty limited: it can display text messages, emails and other alerts as they come in, control music playback on your phone, and of course tell time. It means you don’t have to keep taking your phone out of your pocket.

Other smart watches can do tricks that will probably be combined into some kind of genius watch whenever Apple or Samsung gets around to making one, which will then probably eat the entire category. For example, with the click of a single button, the Cookoo smart watch can send commands back to your smartphone, like “take a picture” or “check me in on Facebook at my current location.” The possibilities seem endless. For example, what if one of those commands was, “start beeping at me once every hour, and if I don’t turn it off, call 911”?

The Leikr smart watch, designed by a group of ex-Nokia engineers, is in some ways the most futuristic of the bunch. On its extra-large, high-resolution display, it can show you exactly where you are on a map, using its built-in GPS. It’s intended for runners, but it looks like nothing less than the phone-watch of the future. The Mio Alpha, meanwhile, can monitor your heart rate constantly, which suggests all kinds of medical applications.

One watch that stands out for its shape alone is Central Standard Timing’s CST-01. It appears to be the world’s thinnest watch, and yet it contains a display, a microprocessor and a battery. Miniaturization of all of these elements is proceeding apace, and while we might not end up with a true smart watch in these dimensions—and certainly not a smartphone—for another 10 years, the trend is clear: electronics are now small enough to wear, and some day they’ll be so small they’ll come close to disappearing altogether.

Atop your head

Reebok CheckLight

That thing on NASCAR driver Paulie Harraka’s head that looks like a spandex skullcap is in fact a self-contained computer. It’s made possible by what is by far the most revolutionary technology in this entire list, produced by a company called MC10. Calling MC10 ambitious is like saying Oracle CEO Larry Ellison likes to sail: The company’s goal is to make conventional microchips as flexible and elastic as human skin. Ultimately MC10’s systems could be incorporated into everything from clothing to the inside of your body, in the form of medical implants.

In collaboration with Reebok, MC10 has created the CheckLight, a cap that measures the force of an impact and can instantly tell a coach (or a racecar team manager) whether someone’s head has just received a blow strong enough to pose a risk of concussion.

On your skin

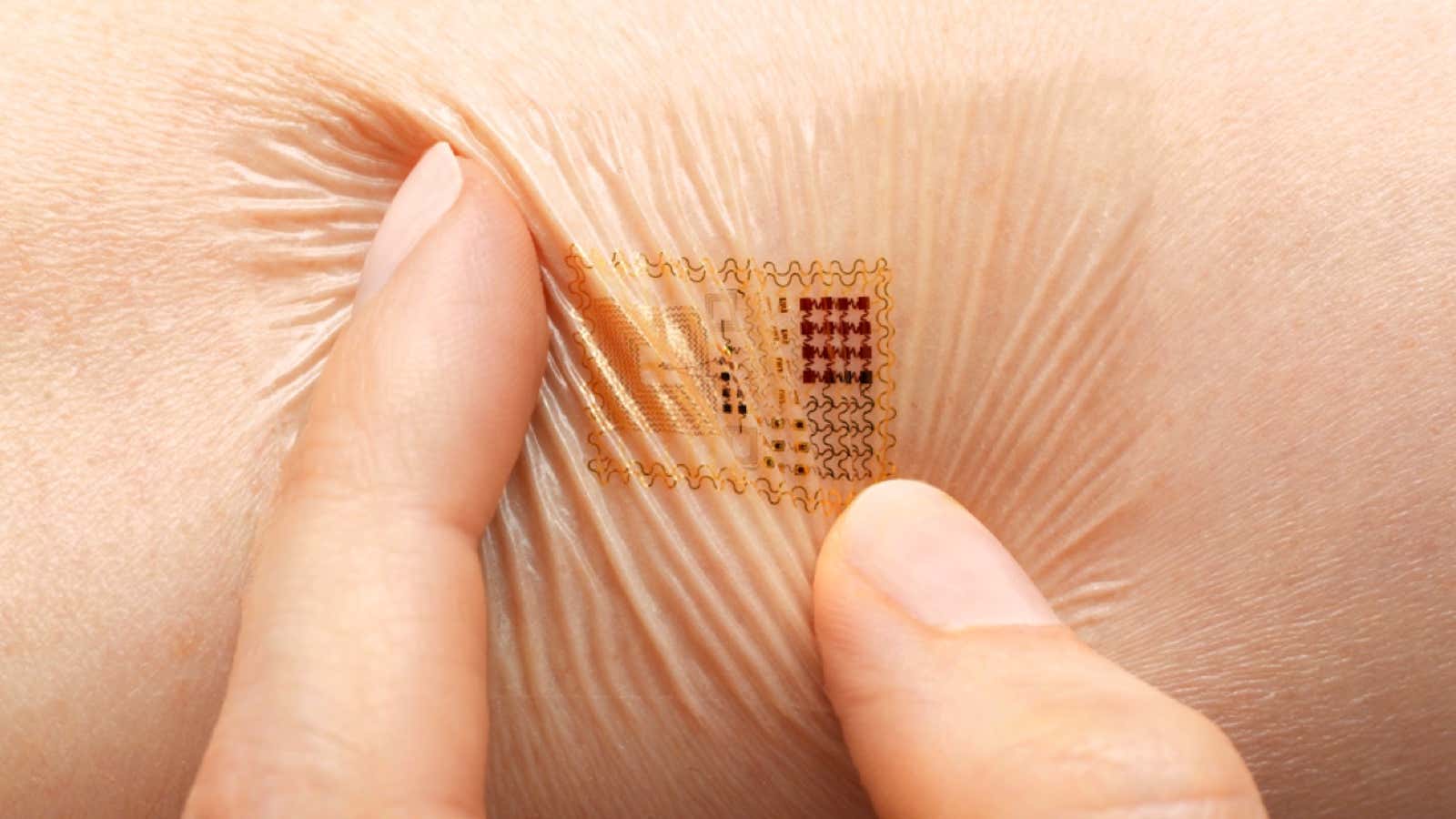

MC10’s Biostamps

MC10’s “biostamps” embed its flexible circuitry in plastic that can be stuck to human skin like a temporary tattoo. The result are sensors for heart rate, perspiration, impact, and so on that can record data that can later be read by RFID—the same technology that enables tap-to-pay systems on key fobs and mobile wallets. No wonder the company just got another $10 million in a series C round of financing.

In your pocket

Withings Smart Activity Tracker, Evado Filip

Not everything needs to be fixed to our bodies directly, and some day our keys might be replaced by a handful of tiny computers we can take with us or not, as our needs change. the Withings Smart Activity Tracker is such a device. It tracks the usual things, but its makers are adding more intriguing capabilities, such as monitoring air quality, which plays a big part in people’s long-term health. It’s so small that it can go anywhere—in wristband, on your belt, etc. We don’t even own these devices yet and we already don’t know where to put them all.

Some devices might not attach to your person for a specific reason. Kids lose and break things, so if you want to keep track of where your kids are, you might be better off attaching a GPS tracker like the Evado Filip to their clothing or backpack. We already track lost phones and lost cars—kids are a logical next step.

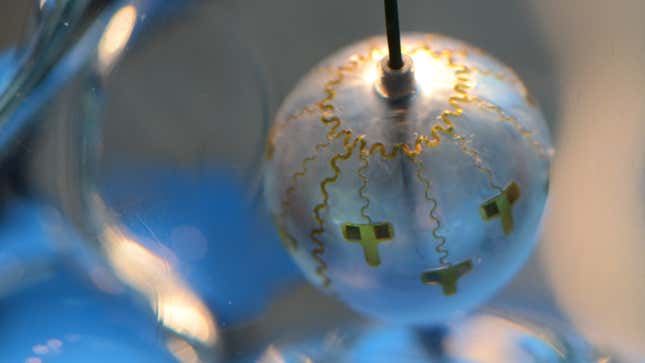

Inside you

When I interviewed one of the engineers behind MC10’s flexible circuits, he told me that one of his goals was to eventually create an artificial pericardium—the sack that surrounds the heart—and infuse it with a mesh of his flexible circuits, all firing in a precise and reactive way, to act like a much more sophisticated and precise pacemaker for a diseased heart. Already, MC10 has created a prototype balloon catheter equipped with sensors that can measure electrical misfiring caused by cardiac arrhythmias.

Taken together, these devices represent something consumers have never really seen before—a body-based network of input and output devices that travels with us wherever we go. If it’s hard to imagine how any one of them might change our lives, what’s completely unpredictable is what they’ll do when combined. It’s exactly the sort of opportunity the consumer-electronics industry needs to lift it out of its doldrums. And the companies that can capitalize on that will be entering an industry with tremendous room for growth—because it doesn’t really exist yet.