Despite already extremely high valuations, the incredible run-up in biotech stocks continues. The Nasdaq Biotech Index is up 20% this year after five straight years of outperformance, and short interest is at a low.

Putting all this in sharp relief is Axovant Sciences, a very recent addition to the pantheon of public biotech companies. It went public on June 11 at $15 a share. The price popped 99% that day:

It was the biggest biotech IPO on record, raising $315 million and generating a $2 billion valuation for a company that is based on a single drug—one that another company had given up on some time ago. It is intended to treat a disease with the highest rate of drug failures (Alzheimer’s), and is based on a method that has failed repeatedly in the past for other drug companies.

Still, Axovant and its shareholders seem to be betting on the idea that GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the former owner of the drug, completely overlooked a potential blockbuster.

GSK presumably has a rigorous process for evaluating the potential and value of drug candidates. It saw how this drug performed in people in phase 2 trials, following an already significant investment, and didn’t think it was worth pursuing. But while the drug failed on its own, it did show a (small) effect when combined with another drug that’s already approved, which is what Axovant is now pursuing.

It’s true that GSK is focusing more on its respiratory franchise, vaccines, and over-the-counter drugs. But if this drug proves to be a winner, it would have been a pretty spectacular oversight.

It would be one thing if this were a novel molecule with better-than-average prospects for approval. But it’s one of several drug candidates targeting the same thing. It does not attempt to treat the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s, unlike other high-profile drugs entering phase-three testing; it is meant only to slow cognitive decline.

And there are other company specific reasons to be wary of Axovant’s valuation. The company says nearly a third of the IPO proceeds will go just toward paying for phase-three trials (the same stage GSK decided wasn’t worth pursuing). These tests are extremely expensive, and tough to manage for large pharma conglomerates, let alone a nine-month-old company that has never attempted one, for a category of drugs that’s especially prone to failure.

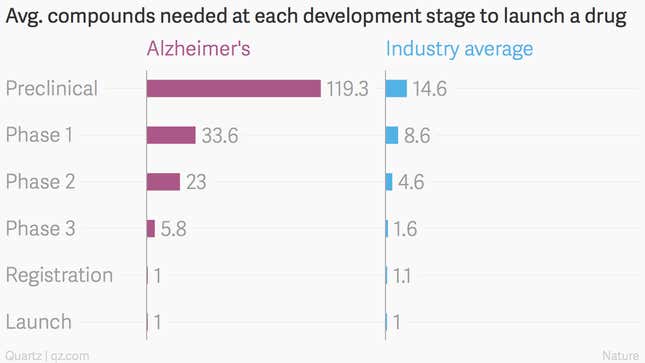

On average, only 1 out of every 5.8 Alzheimer’s drugs that makes it to phase-three trials ever moves forward. The average for all other diseases is 1.6 candidates:

It’s a pretty remarkable market that can turn a $5 million purchase of a seemingly failed drug into a multibillion-dollar company. But Axovant is far from the only pre-revenue, pre-approval biotech to reach a valuation of $1 billion or more, based on a drug with extremely uncertain prospects.

As the Wall Street Journal points out (paywall), 94 of the 146 companies that make up the Nasdaq biotech index had less than $100 million in revenue in the past year. Increasingly, it looks like even the smaller, riskier companies are benefiting from the run-up in values of companies that actually have drugs on the market already, or have molecules that have an excellent chance to make it.

It might take a high-profile failure or two to correct that mindset, as investors don’t seem particularly concerned about risk.