Ever since environmentalist Charles Moore discovered the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 1997, the most common representation of human attempts to deal with that trash vortex have been depressing photos of albatross carcasses filled with plastic debris, plus a few abstract infographics of the Pacific Ocean’s circular currents.

Compared to that, the image of a blue-eyed boy standing in front of the pile of trash he collected is a relief. Add the fact that this particular boy is about to lead the largest expedition in history to map the spread of trash in the Pacific Ocean, and relief legitimately upgrades to hope. And when he says that—within one year—he will launch the first global system for cleaning the world’s oceans, it’s worth listening to his story.

In 2011, while diving in Greece, then 16-year-old Boyan Slat noticed that he was surrounded by plastic bags, rather than fish. Back to his high school in Delft, Holland, he did some research and found that every year, up to eight million tons of plastic are thrown into the ocean. Much of that plastic, although eventually broken down into tiny pieces, is not biodegradable. It poses a threat to seabirds and marine mammals, causes financial damage to industries from shipping to tourism, and enters the food chain, posing health threats to humans.

Carried by ocean currents, that plastic drifts in five gyres: huge systems of rotating water currents. The largest is the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, which spans around 20 million square kilometers, and, according to Charles Moore, would take 79,000 years to clean up with a fleet of ships.

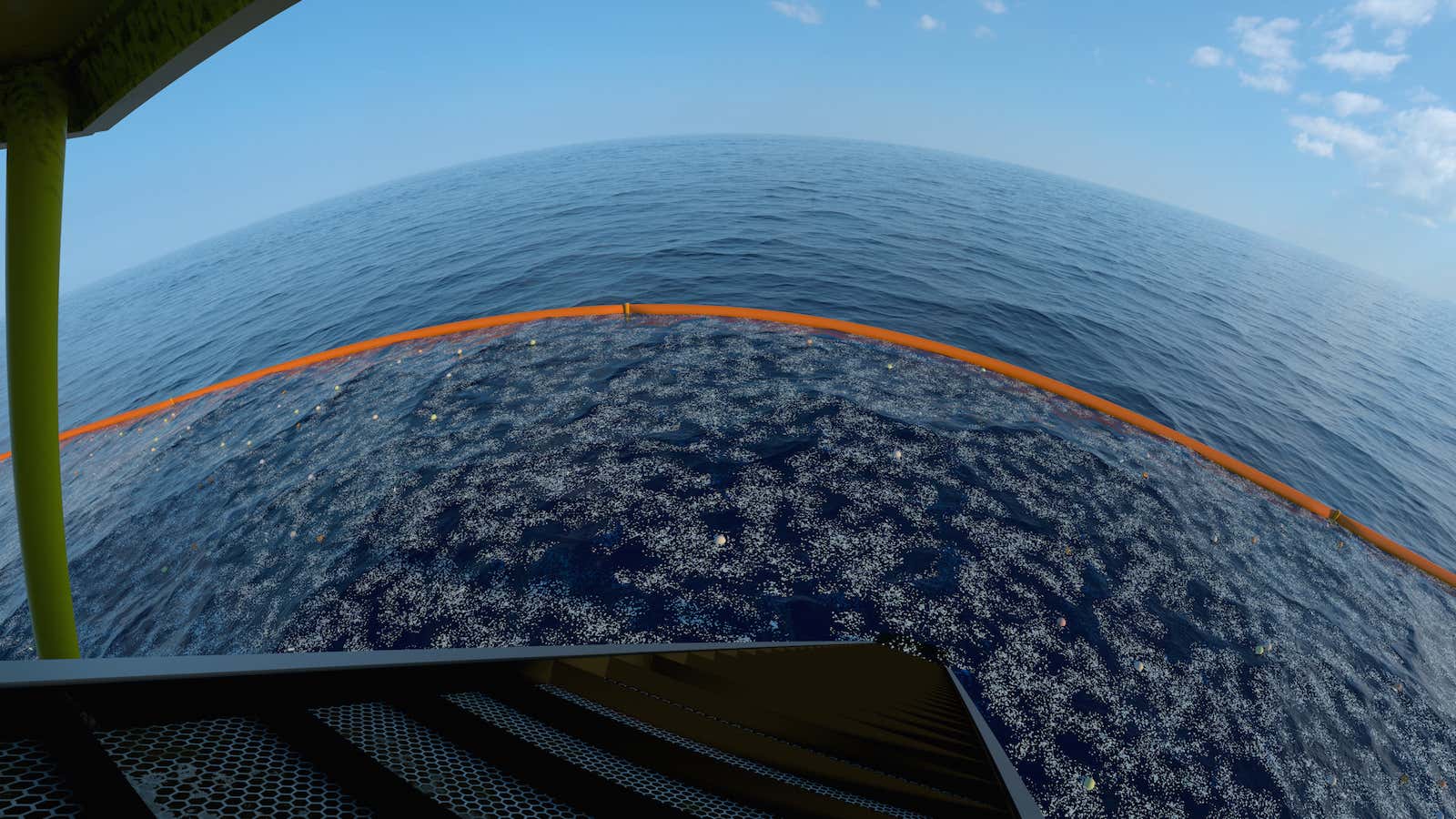

A gyre is a moving target, but Boyan saw the movement as an opportunity. After a series of rudimental experiments, he devised a shipless system in which an array of floating barriers anchored to the bottom of the ocean would catch debris carried in by the currents, while letting sea life pass underneath it.

It was no more than a student’s bizarre hypothesis, until March 2013, when a video of Boyan presenting his idea at Tedx Delft went viral, getting more than 2 million views on Youtube. By June 2014, Boyan’s Ocean Clean Up Foundation, had raised over US$ 2 million in more than 160 countries to fund his project. Today, he works in Delft with a team of 100 researchers from the fields of engineering, physical oceanography, ecology, finance, maritime law, processing and recycling to implement his idea.

As usual, not everyone is impressed. “Critics think there is a high danger that cleaning up parts of the plastic might lead to the impression that a reduction of plastic garbage and influx into the oceans isn’t all that necessary,” Boyan, now 20, tells Quartz.

“My answer is that it is of course essential to prevent more plastic from reaching the oceans in the first place, but that is not a solution for the plastics already trapped in the currents of the gyres.”

But San Francisco-based NGO Project Kaisei estimates that only 30% of marine debris actually stay on the surface, while 70% of it sinks to the bottom of the ocean where Boyan’s barriers will not reach.

Tony Haymet, a professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at University of California, argues that the microplastics like the ones found in the gyres are so small that they’re virtually impossible to extract from water.

Nonetheless, after an intensive feasibility study released in 2014, Boyan’s project is proceeding at full speed. A research expedition aimed at collecting “more plastic measurements than have been collected in the past 40 years combined” is planned for August 2015. It will involve up to 50 boats—the Ocean Clean Up website currently has a call out for volunteer skippers and boat owners to sail with them across a 3,500,000 square kilometer area between Hawaii and California.

The goal is to create the first high-resolution map of where all the plastic floats in the Pacific Ocean, a fundamental step toward cleaning it up. Current estimates of how much plastic debris lies in the ocean vary greatly.

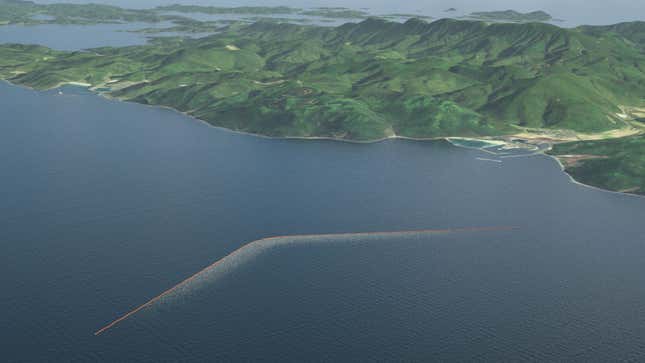

The next step will be a floating structure two kilometers (1.2 miles) long, which will be released in 2016 somewhere between Japan and South Korea, with the aim of catching plastic trash that would otherwise end up on the shores of Tsushima Island, in Japan.

The success of that structure will decide the future of a 100 kilometer (62 mile) system planned to be deployed in 2020 between Hawaii and California, which Boyan expects to clean up about half of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in the following 10 years.

“Our ambition is still the same,” says Boyan. “Cleaning the oceans from plastic.”