The value of any analysis depends, to a large extent, on the beginning and ending you choose.

So it is with Greece, which is seeing its simmering, half-decade-long debt crisis come to one of its periodic boils—and perhaps a final explosion.

Where to start? Records of Greek public debts stretch back at least as far as the Peloponnesian war—around 400 BCE. Should that be included? Or how about the fact that the modern nationstate of Greece has been in default for roughly half of the years since it gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in the 1830s? (After all, some trace Greek resistance to taxation to the historical taxes levied by the conquering Turks.)

For simplicity’s sake, let’s just start in the years before Greece joined the euro. In the 1980s, and early 1990s, the Greek economy was a bit of a mess.

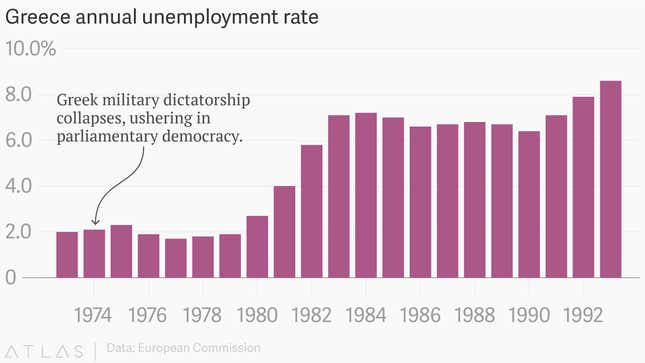

Unemployment was high by recent standards. Greece experienced something of an economic boom after World War II, as its economy shifted from an agricultural to industrial base. But after the collapse of a military dictatorship in the 1970s, the economy was again struggling.

Prices were surging. The end of the military dictatorship sent the country into an inflationary spiral. Between 1973 and 1993, inflation ravaged the economy, averaging roughly 18% annually.

Government debts ballooned. The government tried to jumpstart the economy with deficit spending policies.

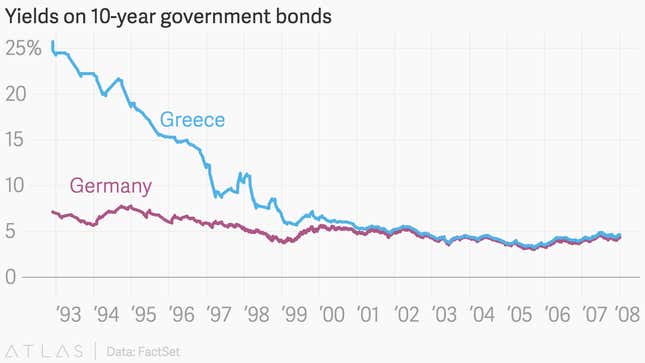

As a result, Greece’s borrowing costs were sky high. This made sense since investors wanted to be compensated for the inflation and default risks of lending to Greece. On the eve of Greece’s entry into the euro zone, its borrowing costs were starkly higher than its future monetary union mates.

Nevertheless, Greece became the 10th member of what was then known as the European Economic Community in 1981. Greece butted heads with Brussels throughout much of the 1980s, but, by the 1990s, the Greek political class had made gaining access to the European monetary union a priority. And, ostensibly, the government began bringing down both inflation and deficits in an effort to satisfy the Maastricht Treaty, which acted as the blueprint for the single currency union.

Greek inflation fell sharply. Over the course of the 1990s, it plummeted to average euro-area levels.

Deficits shrunk. But they didn’t shrink as much as first thought. In November 2004, Greece essentially admitted it had fiddled with its deficit numbers to ensure that its deficit was below the 3% of GDP hurdle that had to be met to get into the euro.

In January 2002, Greece did away with the inflationary drachma and adopted the euro.

Greek borrowing costs plummeted. Adoption of the stable currency, backed by the European Central Bank, installed confidence—and frankly overconfidence—in financial markets. Investors seemed to discard any concerns about the Greek economy, as well as the country’s shaky credit history. Yields on Greek government debt fell to levels on par with some of the most creditworthy countries in Europe, such as Germany. And that scenario persisted up until the eve of the financial crisis and Great Recession.

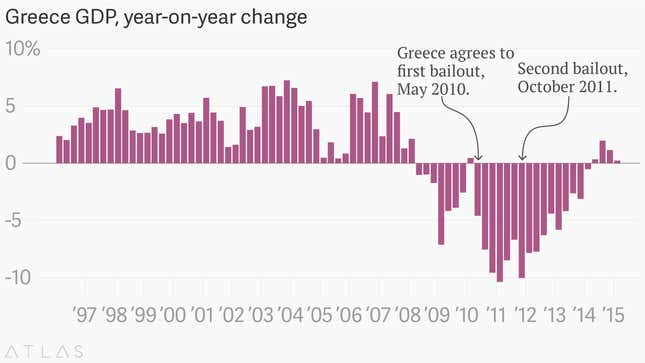

At first, this appeared to be a great thing. The pace of Greek economic growth quickened in the years after it joined the currency union. Between 1996 and 2006, quarterly economic growth jumped an average of 3.9% compared to the prior year. The Euro zone as a whole grew at about 2.2% during that period.

Times were good. Living standards improved, as GDP per capita rose by 47% between 1996 and 2006.

But government finances worsened. The vast improvement that Greece had made during the pre-euro period stalled out, and budget deficits also began to grow again.

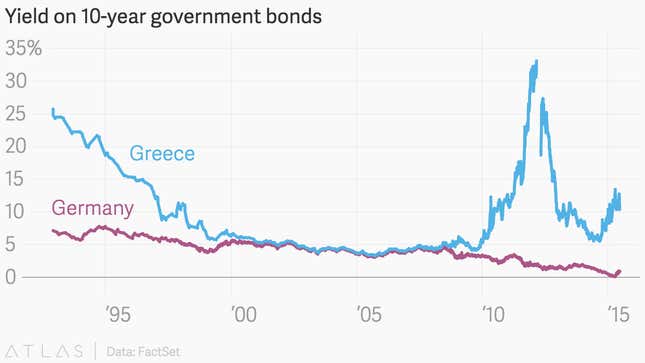

Then came the crisis. Greek debt levels, which remained relatively high in the run-up to the crisis, attracted investors’ attention as growth weakened in 2008.

And then a new Greek government revealed that the country’s penchant for tinkering with economic statistics had flared up again, saying that the deficit was actually 12.6% in 2009, far worse than the 6% of GDP that had been previously announced. Suddenly, investors began to think that Greece was not as creditworthy as Germany, which sent the interest rates on Greek bonds soaring in 2010. The euro crisis had arrived.

The bailouts. Greece secured its first bailout in May 2010, in which the government committed to painful austerity measures in exchange for €110 billion ($145 billion). But the austerity measures helped send an already weak Greek economy into a tailspin. A second bailout did little to resuscitate the economy either. The recession, one of the worst in Europe since the Great Depression, has cut the size of the Greek economy by roughly 25%.

Unemployment is an obscene 25%. And it shows little sign of declining.

Meanwhile, the country’s debt load has only gotten worse. Though the bailouts briefly cut the debt load, the key debt-to-GDP ratio has continued to rise as GDP has collapsed, making the debts harder to pay off. In other words, for all the pain the Greek economy has suffered, the country is no closer to debt sustainability.

Which brings us to today. The embattled Greeks voted a left-leaning coalition of parties to power in January 2015. Led by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, Greece has negotiated to end the austerity measures it blames for the worst of its recession. But with Greece unable to strike a new deal with creditors, a slow motion run on Greece banks has gotten underway in recent months.

That’s made Greece’s banks increasingly reliant on funding from the European Central Bank.

And that funding abruptly ceased after Greek leadership called for a referendum on whether the country should accept proposals from international creditors. As a result, Greece has imposed capital controls—effectively limits on what people can do with their money. And the country has also shut the banks for roughly a week.

What next? Nobody knows. European policy makers seem fed up with negotiating with the Greek government. Greek leaders show no sign of stepping back from their plan to hold a vote on creditor proposals. (Even though creditors say those proposals are no longer on the table.) At any rate, what’s truly remarkable is that the Greek drama still has the power to attract the attention of the world, even after five years of crisis.