Photographer David Hlynsky knows what shopping was like in the former U.S.S.R. before the age of capitalism—and according to him, it was better in some ways. Hlynsky’s book published earlier this year, Window Shopping through the Iron Curtain, features photos of over a hundred storefronts in the former Soviet bloc, taken during several visits between 1986 and 1990. He spoke to Quartz about the project.

Quartz: You started out photographing street life behind the Iron Curtain and then decided to focus on the shop windows. Why the windows?

David Hlynsky: Images of people wearing unfashionable clothing can play too easily into the stereotypes entertained by Western politicians and media. I wanted to find a different way to describe the human condition we all share. We have lived under different political systems. Neither has been a perfect experiment.

We should also remember that when this project began in 1986, East and West were still brandishing our extravagant nuclear arsenals. A diplomatic slip, a moment of madness or computer glitch could trigger a global firestorm. I wanted to make pictures of what we had in common. If not the goods in our shops, at least our common needs for these goods. I use the shop windows to remind us of our familiar, basic needs.

Q: What do you mean by familiar basic needs?

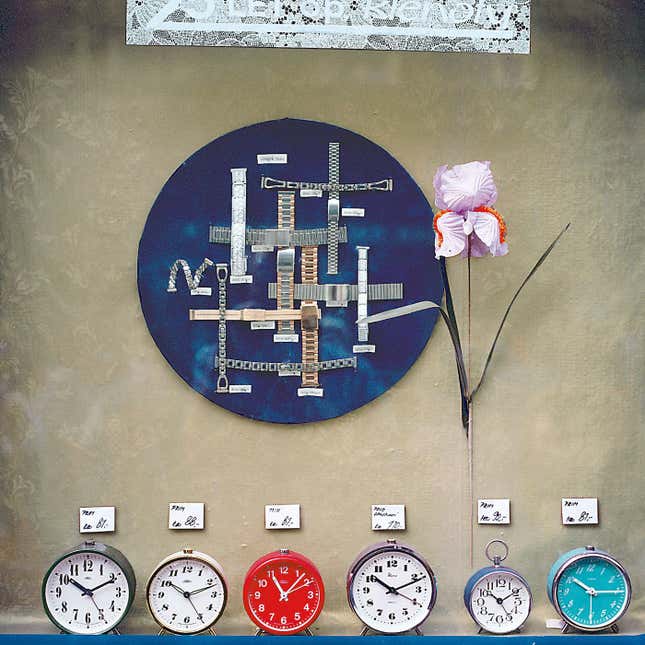

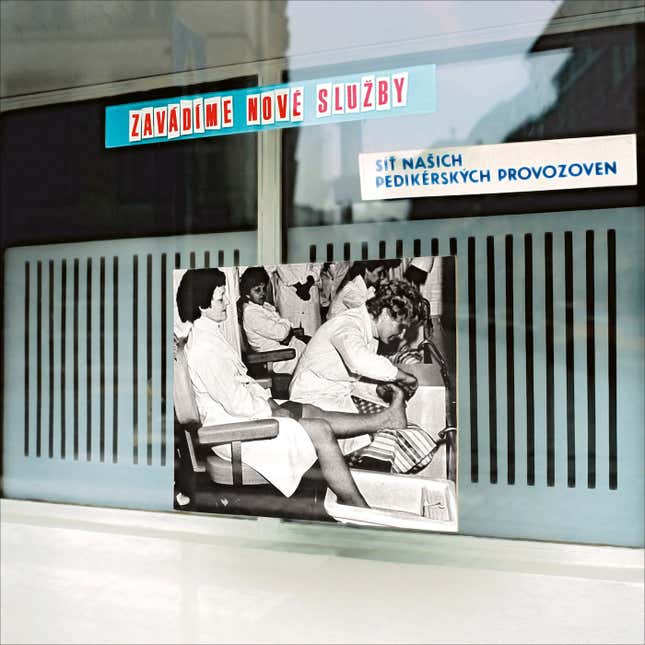

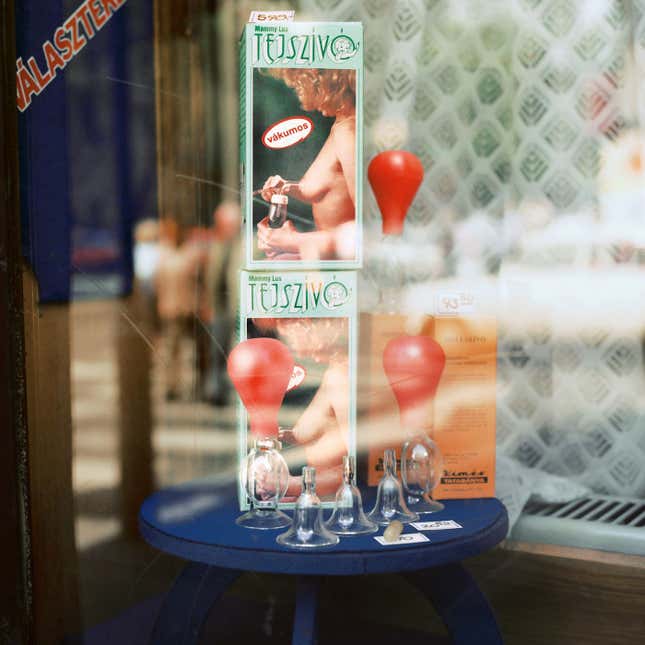

DH: Every window in my collection corresponds with a typical commercial window in the West. I have consciously created a cultural inventory of familiar products: bread, meat, clothing, fast food…Each time my viewer sees one of these, there is an automatic comparison with its Western counterpart. The differences in presentation stand out. The capitalist aesthetic verses the communist aesthetic. We did all need the same things.

Q: You say in your book how the East collapsed because its marketplace of ideas finally ran out of promise, but that for you the East Bloc windows were far from bankrupt. What do you see in them?

DH: My own experiences growing up in Western cultures imprinted upon me the fact that every commodity was one brand or another. These brands compete with one another by hiding within differing seductive fantasies. We try to choose quality but are often distracted by branding that place us in one desirable social group as opposed to another.

When I saw East Bloc shop windows for the first time, it took a very long time to realize that there was very little branding. These windows never tried to tell me who I was, wanted to be or ought to be. Rather they were simply labeling the product for its function. One might observe that this represented a lack of variety and perhaps it did. But it also represented a reduction in consumer pressure.

Q: So there was more common ground between East and West than we realized at the time. Do you believe there could or should have been a political system that meets in the middle?

DH: I hope that we will eventually recognize a middle road between the two systems. Unfortunately the fall of the Soviet empire was interpreted as a license for multinational corporations to expand resource extraction, labor exploitation, and market penetration as never before.

As an artist I see the cultural side effects of these changes and the potential dangers. We have come to believe that economies will have unlimited growth and that each of us is entitled to a super-sized deluxe share. Commercial advertising promises that we will all live in consumer heaven. Instead, we get landfill sites bursting at the seams. Hidden in our shopping sprees are the byproducts of refined metals, petrochemicals and farmed wood. We are obliged by social pressure to borrow beyond our means and achieve the fantasies we see in advertising.

Q: What has been the most interesting response to your photos?

DH: The most interesting response I have had to my pictures is a near universal sense of the unexpected. We all imagined the shadowy Cold War streets, but didn’t imagine casinos, hobby shops, ice cream stands, photocopy services, flowers, and lace curtains and cartoon children. And we didn’t imagine a landscape nearly devoid of advertising.

Q: Have you been back to see these same shop windows? How have they changed?

DH: Yes, the cityscapes have changed. I often imagine it as if a gigantic hypodermic needle full of money was thrust into the pavement of Wenceslaus Square (Prague) or the Brandenburg Gate (Berlin). Money oozes through the pavement. Western fashion franchises and fast food restaurants bloom where quiet shops once were. Pizza and hamburgers, pop and printed tee shirts, Chinese-made replicas of buildings and monuments, fragments of the wall in plastic bags. Then come the sports bars and strip clubs and casinos with twirling lights. Western logos burn through the night. Real estate prices go up. Natives move away.

Gradually it begins to look like a mall in Cleveland coupled with the side streets of Niagara Falls. What has been lost? I think a measure of cultural diversity. It was quieter before. The architecture seemed more stately. It felt as if people had lived here for a very long time. It felt more studied, wiser, more well crafted, more respectful of art and tradition. There was less chaos and litter.

Q: Is there anywhere in the world that you feel like this way of life still exists?

DH: I think that even in most Western cities, there remain small family-owned shops. I think that these often embody a neighborly self respect that is immediately diminished when a multinational franchise moves in. Corporate calculus replaces simplicity with efficiency. Billions of burgers get sold… all exactly the same. Life behind the Iron Curtain was never simple but, because the state was so inefficient, ordinary people depended on interpersonal navigations to survive.

Q: Is there one thing you hope people take away from seeing the photos?

DH: The world of people and things is always vastly more complex that we first imagine.

This interview has been edited and condensed.