A visit

One afternoon not long ago, I was skimming the Whitney Museum of American Art’s website when suddenly my screen went black.

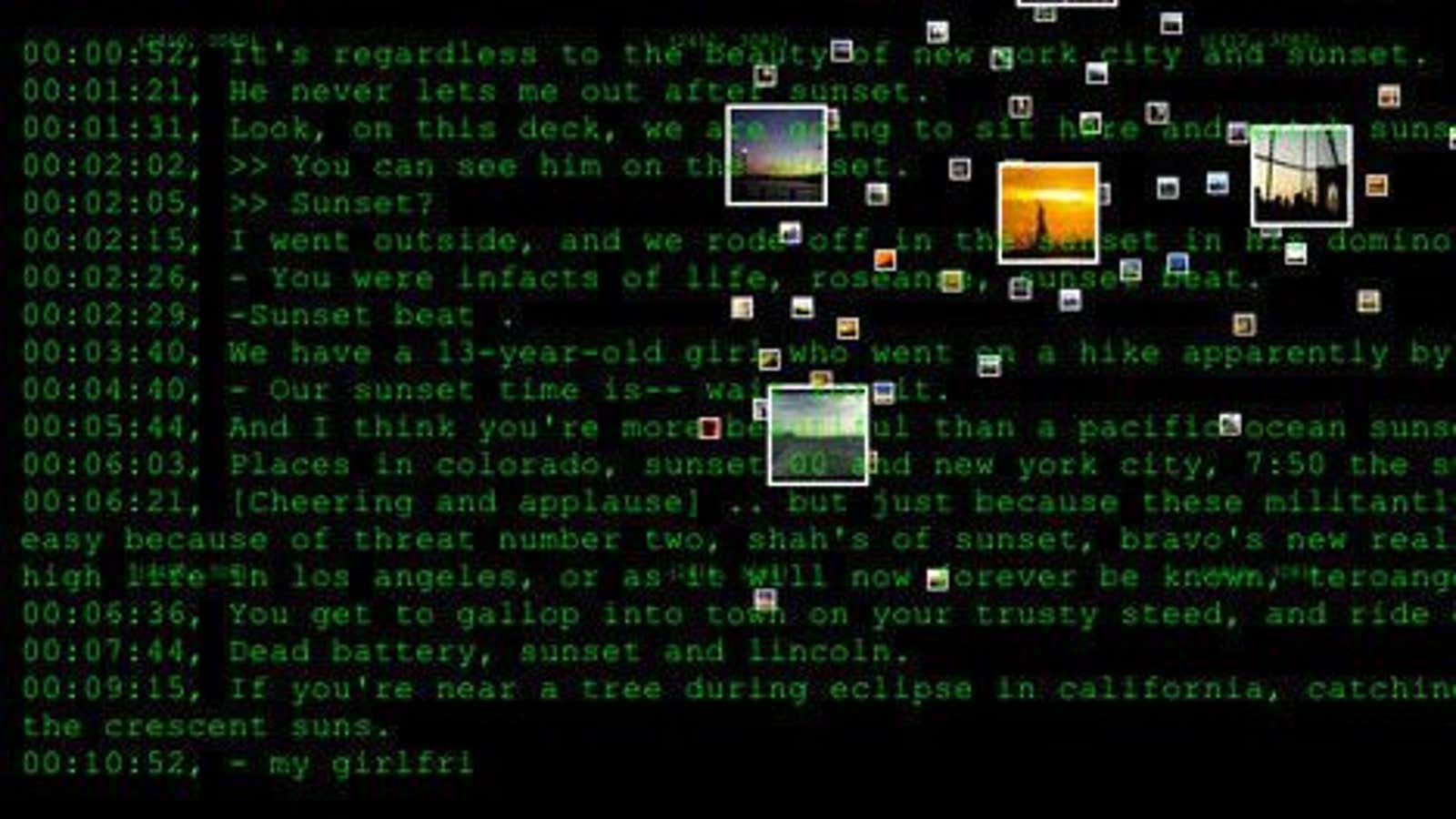

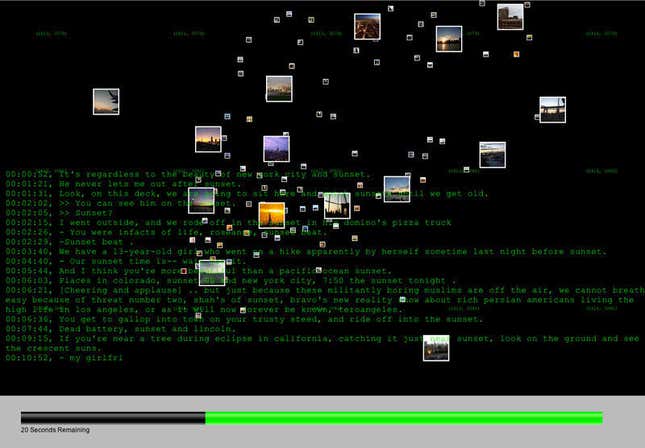

Bright green text started scrolling across it, one line at a time.

“Look, on this deck, we are going to sit here and watch sunsets until we get old.”

“You get to gallop into town on your trusty steed, and ride off into the sunset.”

I stared at my friend sitting across the table.

“I think I’m being hacked.”

Tiny color thumbnails of skies and cityscapes began floating over the text.

“I think Edward Snowden is contacting me to wax poetic about sunsets.”

Then, as quickly as it appeared, the ghost was gone. I didn’t even have time to take a screenshot. In less than a minute, I was back to the page I had been on.

“He must be really bored in Russia,” I thought.

It’s art, stupid

What I took to be a visit from a hacker was actually part of a 30-second art project that runs twice every day, once at sunrise and sunset (New York time), all over the Whitney’s website, to mark the passing from day to night and vice versa.

The Sunrise/Sunset project is now in its sixth installation since it launched in November 2009. The current piece, by Dutch-Brazilian Internet artist Rafaël Rozendaal, launched on May 1 to commemorate the museum’s reopening, following its relocation from the Upper East Side of Manhattan to a new building in the city’s Meatpacking district.

Christiane Paul, the Whitney’s adjunct curator of new media arts, oversees the museum’s online gallery and commissions all of the Sunrise/Sunset pieces. She says that sometimes “people do write emails to say, ‘I think your website is broken.'”

But because the disorienting experience is so short, she says, “It’s worth the risk of people coming to the site and being surprised, wondering, ‘What’s going on here?’ and ‘Is Edward Snowden contacting me?’”

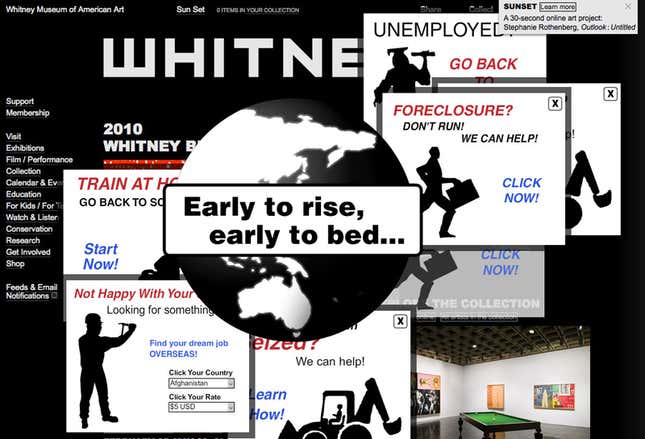

Stephanie Rothenberg’s “Outlook: Untitled,” which ran from March 2010 to March 2011, was a “frenzy of faux pop-up advertisements referencing the current world economic crisis,” according to the Whitney site. A Magic 8-Ball appeared on the screen and allowed users to try it out before it delivered fake forecasts about the crisis. This piece in particular, says Paul, prompted a spike in emails from confused vistors.

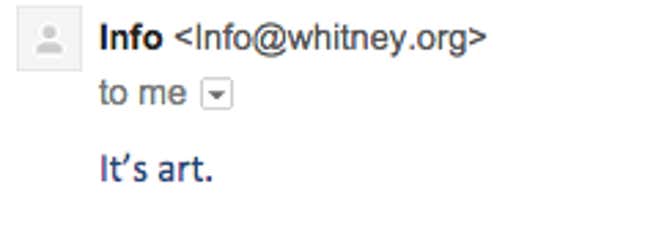

Indeed, in trying to figure out what was going on with my own computer, I had also emailed the Whitney about the takeover. I got this response:

Almost there

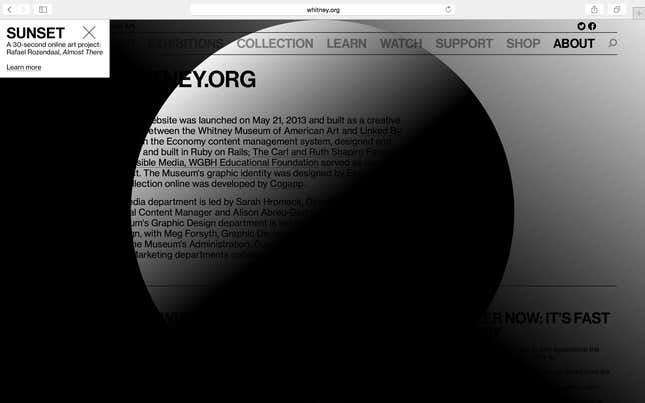

Today, as the sun sets on New York, visit the Whitney website and you’ll find your screen suddenly split into black and white. A half-moon in the middle of your screen rotates as you move your cursor around the site, occluding different parts of the text like a pirouetting eclipse.

“Almost There” is intended to recreate the experience right at the moment of falling asleep. “You don’t have a lot of control,” says Rozendaal, “and it doesn’t matter if you move left or right. It’s counterintuitive and kind of annoying.”

A happening

It can be tough to catch these art pieces, and even tougher to share them with other people. You have to be on the Whitney’s site exactly at the moment of New York’s sunrise or sunset, and you have to be on a desktop computer (sadly, the project doesn’t work on mobile).

Net art—art designed for the Internet—is meant to embrace accessibility by eschewing a geographic location, making time-specific (and timezone-specific) art like the Whitney pieces feel strangely exclusive. “It means only a few people will see it, but it’s interesting. It’s kind of a secret,” says Rozendaal.

This kind of net art is actually more like live performance art: At a prescribed time, it locks you into one place, transfixing you with the immediacy of something weird, fleeting, and just for you.