In most places, my hair and my skin color don’t stand out in a crowd. In the past, people have mistaken me for Mexican, Italian, Hawaiian, and Israeli. Although sometime this has felt like a privilege and a reason for pride, at other times it has become a source of confusion and guilt. This is the reality of my mixed race identity: half-Japanese and half-white, I still couldn’t tell you whether I technically qualify, or even identify, as a person of color.

Five years ago, I applied to college in the US and was forced to face this confusion head on during the university admissions process. 2010 was the first year that the Common Application offered the option for applicants to select two or more races. This has been both a blessing a curse for schools that have long wrestled with students who identified as multi-racial. A decade ago, such applicants at Emory University would have had their race literally chosen for them by an admissions officer.

But my problem was first and foremost a personal one: How did I identify? Growing up in a very white, yet liberal-leaning community in Southern California, I always wanted to identify with my Asian half in order to stand out. I would squint my eyes in photos to appear more Asian, and ask my mother to pack me bento-box lunches. On standardized tests, I always checked the “Asian/Pacific Islander” box.

But that changed in high school, when to fit in I started playing up my white half, wearing certain make-up to highlight my Caucasian features and adopting the language and style of my white classmates. In my experience, race has always been at least in some respects, a performance.

The second problem was a practical one. Technically, all three options—white, Asian, both—were truthful. In the ruthless competition that is college admissions, prospective students will often do anything they can to increase their chances of admission, and I found myself wondering if selecting white was more strategic than Asian. According to a 2005 Princeton University study that measured how race effects admissions decisions, Asians lost the equivalent of 50 SAT points while African-Americans and Latinos gained 230 and 165 SAT points, respectively.

Labeled the “model minority” by the media (a term I personally find problematic), Asians make up nearly 40% of the student population at certain top-level universities including UC Berkeley and Cal Tech, despite census data that shows they represent a mere 5% of the US population. In fact, some people even believe that universities, including elite schools in the Ivy League, have a secret Asian quota, similar to the secret Jewish cap researchers allege existed in the 1920s. This perceived discrimination against Asian American applicants is also the basis of a complaint filed against Harvard in May.

For me, identifying as Asian did not seem like the smart choice. But nor did choosing to be white.

In the end, I chose to check both Asian and white. It felt like both the most honest and advantageous option. What I didn’t realized at the time, however, was that selecting multiple races is still potentially problematic for someone like me who is half-white. By doing so, you are symbolically placing yourself in the same category as those who select “African American and Asian” or “Native American and Hispanic,” groups for which there are systemic, often very different, barriers in place.

Then there are more concrete concerns. If colleges are short on financial aid funding, they may be more inclined to select the person who is half-white. On average, white families have significantly higher incomes than all minority groups besides Asians, and may be less likely to need financial aid. In this way, the mixed race category arguably subverts the original intent of affirmative action in college admissions, which is to increase opportunity for disadvantaged groups.

It wasn’t until 2000 that the US Census added bi-racial/multi-racial as a category. While this addition to the census is certainly a step forward, colleges should be thoughtful in how they utilize it as part of their own admissions processes. Putting “Asian and white” or “African American and white” or “Latino and black” into a single category is reductive, and ultimately groups together a vastly diverse group of people that have little in common from a socio-historical perspective. Although it may seem difficult—and probably more work for admissions officers—colleges need to start taking into account the specifics of multi-racial backgrounds if they truly want to preserve the original intent of affirmative action.

Today, I’m considering applying to MA programs. If and when I make it to the race bubble, I’m not sure what I will do. Identifying as mixed-race continues to feel like the most honest response, and I’m tempted to call this an institutional problem, not a personal one. The hard truth, however, is that for now, the most honest answer, unfortunately, may not be the most ethical one.

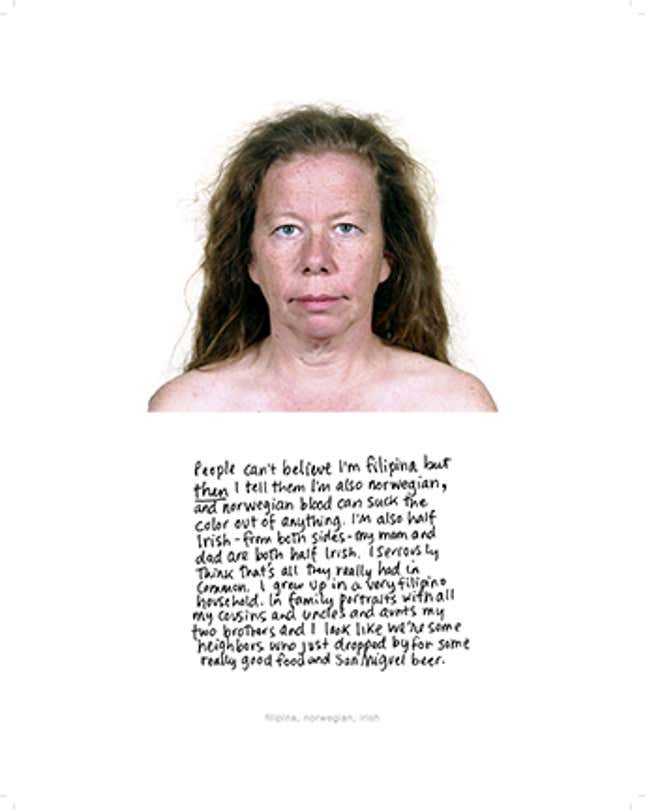

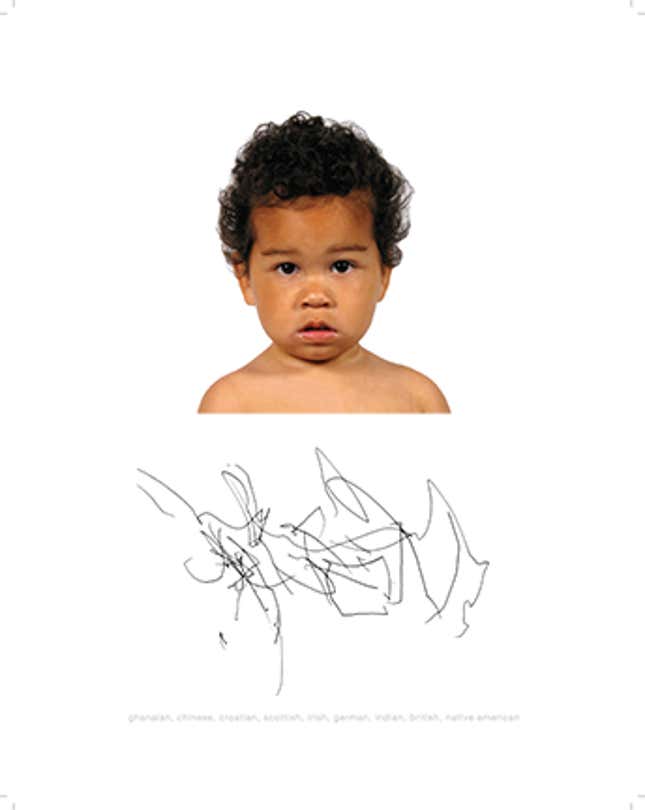

All photos for this piece are courtesy of the HAPA Project and Kip Fulbeck.