Shoppers walking down the produce aisle in search of peaches for their grandmother’s famed summertime pie may soon check the price tag and find something they’ve never seen before: “Country of Origin Canada.”

As climate change warms the planet and growing regions shift further north, more fruits and vegetables—even citrus fruits—could start making the journey to the United States from Canada. Extreme winter cold and shorter growing seasons historically have prevented certain crops from being grown there, but as temperatures rise and first frosts happen later, the time could be ripe for Canadian farmers to expand their ranges.

“We’re seeing that here in Canada, particularly in Southern Ontario, people are pushing the limits,” John Pedlar, a Canadian Forest Service biologist, said. Pedlar helped author a study last year that found that a shift in growing regions may be more closely tied to climate change than previously thought.

“We’re starting to see a lot more grapes grown up here,” said Pedlar, whose work was published in the journal BioScience. “People are trying their hand at things like peaches a little further north from where they have been trying. Presumably, that kind of thing is just going to increase.”

The lowest temperature lows have helped US farmers and gardeners determine what species they can plant—and when they can plant them— for decades. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) released its first Plant Hardiness Zone Map (PHZM) in the early 1960s, and over the years, the map’s recommended zones have been based on the average extreme minimum temperatures over a prescribed number of years.

The latest release, the 2012 PHZM, is, on the whole, warmer by one half zone compared to the 1990 map, according to the researchers who developed it. While climate change likely played a role in this shift, they believe the change is primarily due to the more refined modeling and data gathering techniques they used. For example, the 2012 map used the average minimum temperature from 1976 to 2005, while the 1990 map used the average minimum temperature from 1975 to 1986.

Nir Krakauer, a City College of New York professor, believes the USDA’s findings may be more tied to climate change than the researchers originally thought.

Krakauer authored a 2012 study that relied on the actual annual minimum temperatures, rather than the average minimum temperature over a period of years, to determine plant hardiness zones. Using this methodology, he found that the annual rate of change of the extreme minimum temperature increased 2.5 times faster since 1970 than the mean temperature rate; therefore, more than one-third of the United States has shifted half-zones since 1970, compared to the USDA map’s calculation of one-fifth of the United States.

“It was interesting how much warming there’s been in some regions as far as the winter minimum temperature went. In a lot of cases, it’s warmed much faster than the average temperature over the whole year,” said Krakauer, who updates his projections each year with the previous year’s data. With more data, Krakauer’s projections become more accurate.

“Because of the cold temperatures in the Northeast in the last couple years, our trend estimates have gone down a little bit. So we estimate a little less warming than we would have a couple years ago,” he said.

Canadian researchers are finding similar results, and the country’s farmers are taking advantage of the minimum temperature rise.

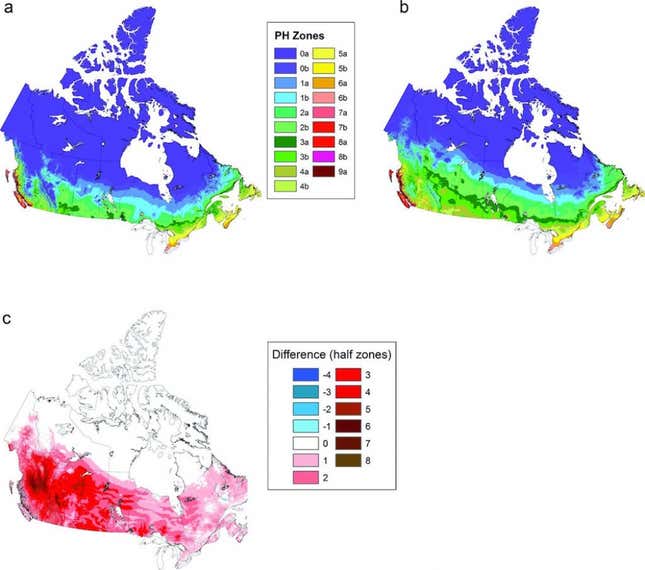

The Canadian Plant Hardiness Zone Maps are similar to the USDA’s, but they take more variables into account, such as the average frost free period and average maximum snow depth. The newest incarnation of the Canadian PHZM showed that when comparing the numbers from 1931 to 1960 to the numbers from 1981 to 2010, the average of the lowest daily temperatures of the coldest month increased by 1.5°C; the frost free period increased by 11 days, on average.

The changes give Canadian farmers more leeway in the plants they can grow, Pedlar said. Even crops like corn and soybeans, which require longer, warmer growing seasons, are now being grown in Canadian spaces they previously couldn’t.

Paul Bullock, a University of Manitoba professor, authored a 2011 study that used computer simulations to determine how rainfall and maximum and minimum temperatures would contribute to the growth of corn. Relying on data from 12 weather stations across the Canadian prairies, he found that warming from the 1920s to 2000 has allowed farmers to plant corn and soybeans in Western Canada, an area that has traditionally been too cold for these crops.

Although the data showed a trend toward warming, there is also great temperature variability each year, Bullock said. Even so, the data can give farmers an idea of the risk involved in planting certain crops.

“At the moment, our analysis is saying that grain corn is not something that could be produced extensively without quite a reasonable amount of climate risk associated with it, despite the sort of changes that we’ve seen over the longer term,” Bullock said.

Dan McKenney, a researcher and team leader at the Canadian Forest Service’s Great Lakes Forestry Center, said this variability will force farmers to be more risk averse and adapt more quickly.

“One thing that we did see was that there are still risks for late spring frosts that can affect plants, and some plant species are more susceptible to that than others. Making use of that type of knowledge by planting certain species or hybrids that are more hearty to later frosts would be a big thing as far as risk management,” McKenney said.

Despite this good news, Bullock remains fearful as to what climate change could bring next for farmers.

“I’m not sure we’re ready to handle the variability that seems to be coming along with some of the changes,” he said. “Variability is what kills us in agriculture. When one year is this way and the next year it’s totally the opposite, how do you adapt to that? That’s extremely difficult to do.”

The story body photo of peaches was shared by bagaball on Flickr under a Creative Commons license. It has been cropped.