First, they suggested taxing Google’s personalized ads to boost French advertisers. Then, they tried to tax Google News to finance the French press.

Now, the French government is thinking about taxing the collection of personal data by Internet companies, according to a report put out Jan. 18. The main target would be American companies like Google, Facebook, or Amazon, whose data mining efforts generate enormous advertising profits but precious little tax revenue for countries like France.

Google, which generates $30 billion in advertising each year, $2 billion of which comes from France, pays very little in French taxes (prompting a recent $1 billion lawsuit), because the companies realizing those gains are not Google France, but Google Ireland or Google US, says Félix Treguer, a frequent French commentator on internet policy issues.

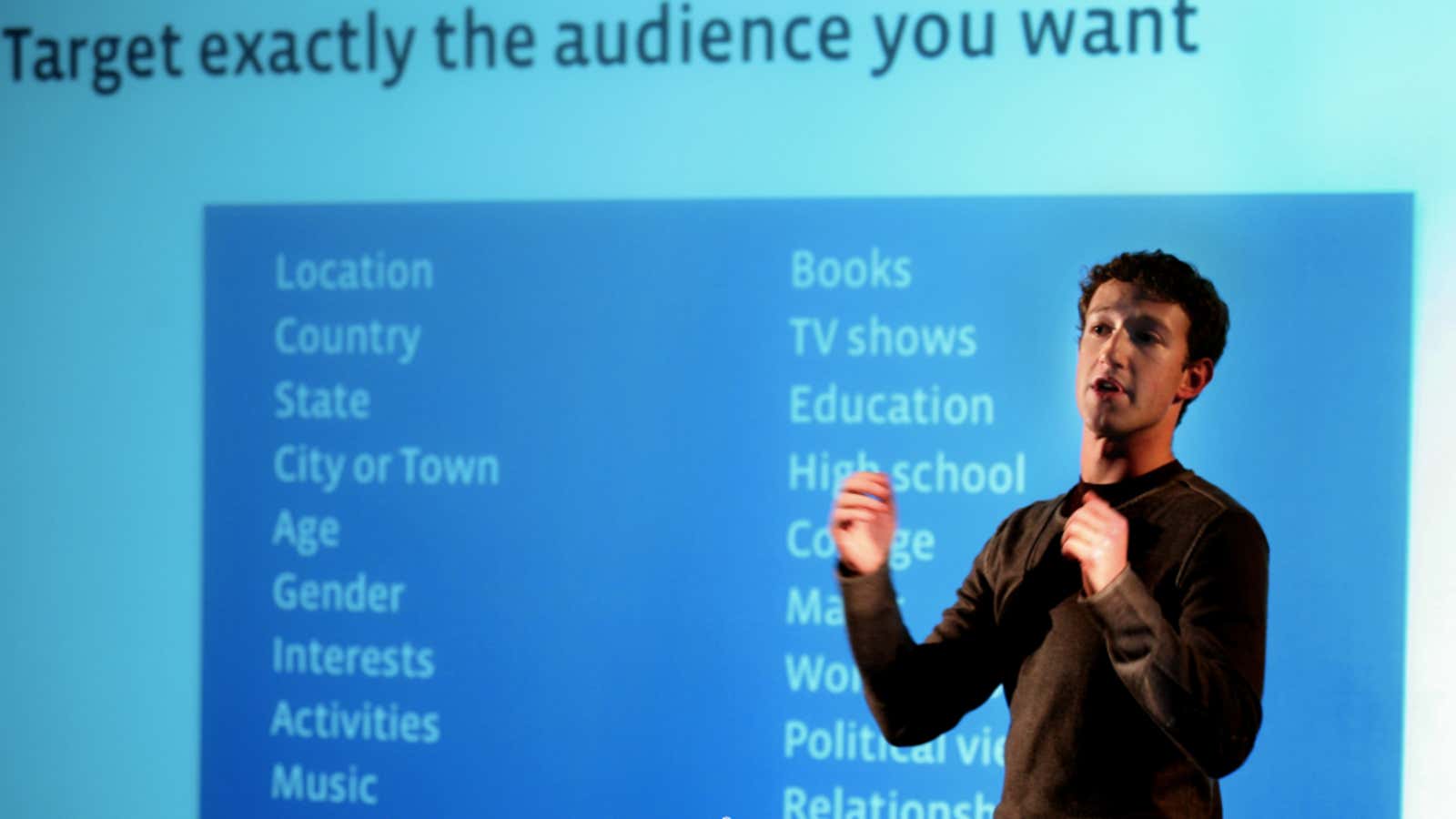

The report’s two authors, Pierre Collin (an advisor to President Hollande) and Nicolas Colin, a government auditor, suggest generating tax revenue from a whole segment of commercial activity—the collection of personal data (called the “raw material” of the digital economy), the subsequent customization of services and advertising, and the profits this all represents—that has allowed for the delocalization of profits from revenue.

Companies like Google don’t pay for the fact that “users, through their bottom up contributions, become auxiliaries in the productive and distributive processes,” i.e. the fact that users put in “free work,” but often cannot modify, block or reuse their own mined data. Thus, the report calls for a tax inspired by a “predator-pays” principle similar to the “polluter pays” concept behind environmental legislation such as the carbon tax.

With slowing GDP and a yawning deficit, and now waging a war in Mali, France is growing increasingly desperate for revenue. Tax evasions from multinationals operating in France have become a central focus. Fleur Pellerin, the French minister overseeing digital innovation, announced the release of the report: “We want to work to ensure that Europe is not a tax haven for a certain number of Internet giants.”

The French government has long been frustrated by American companies that dominate the French digital economy from beyond the reach of French fiscal authorities, but Treguer told Quartz: “Even though the major companies targeted by the report are American, that’s because American companies dominate the internet. Orange Telecom, for instance, will also be affected.”

Yet France has sometimes seemed particularly hostile to foreign technology companies. Treguer said:

“The French government has a record of favoring local press or publishers over companies like Google or Amazon, sometimes to an extreme. The truth is that the French government is captive to these national lobbies. But it’s also the case that the digital economy is fast becoming a very large part of the global economy, yet France’s tax system, and other countries’ tax system, are not adapted to this. In this sense I think it’s legitimate that France is asking itself how it can tax more of the profitable digital activity taking place in France.”

The report is less about fiscal evasion and more about how to properly tax the economy of the future. Though the idea of a tax on personal data is at the heart of the report, no specific tax rates were suggested (though it seems rates would be based on the number of users tracked), nor any predictions made as to how much revenue could ultimately be raised. And though the report was commissioned by the Hollande administration, its suggestions have not yet been officially endorsed. Treguer says, “the goal of the report is not simply to propose a tax on personal data. What the French government is trying to do is determine the appropriate tax base: what are the revenues considered taxable, how are we going to measure personal data, is there a legitimate way to tax the mining of personal data? It’s rare to see government officials in France with creative ideas, but this is a pretty good one.”

Correction (January 21): An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the French government endorsed the report’s proposals. The government commissioned the report but hasn’t yet taken a position on the specific recommendations.