Broccoli, the original superfood, is getting an upgrade.

On top of the Vitamin C, Vitamin K, protein, dietary fiber, and slew of other nutrients found in a typical stalk of broccoli, Monsanto says its Beneforté broccoli will do you even better. It’s bred to have higher levels of a nutrient that your body uses to fight cancer and cholesterol. As Monsanto’s website for the super-broccoli puts it, “Beneforté is even more of a good thing.”

Beneforté seeds were first sold in 2010 and the packaged broccoli arrived in supermarkets in the UK and US in 2011. It’s on sale in the UK in 10 grocery chains, and though it’s not currently available in the US because of a gap in supply, Monsanto expects it to be widely available in 2017.

Broccoli may seem out of step with Monsanto’s corn- and soy-heavy business, but it’s right in line with shifting consumer preferences for healthier, less processed foods. For the year ending June 2015, US unit sales of soft drinks were down 2% and units sold of ready-to-eat cereals were down 4%, while fresh produce sales were up 2% by volume, according to data from Nielsen. Companies like General Mills and PepsiCo are trying to lure customers back with revamped products like all-natural Trix and aspartame-free Diet Pepsi.

If they succeed, so does Monsanto. Its patented genes are in the vast majority of corn and soy grown in the US. But if they don’t—if the trend towards more fresh vegetables and fewer packaged foods continues—well, Monsanto, which has made billions on the ingredients for processed food, is preparing for that, too. And this time it’s doing it without a genetically-modified organism in sight.

Monsanto’s ambition: global greengrocer

Beneforté is no pet project. Since 2005, Monsanto has spent more than $2 billion acquiring two major vegetable and fruit seed companies. That includes Seminis, the world’s largest seller of vegetable seeds, which licensed Beneforté from its original developers in the UK, the John Innes Centre and the Institute of Food Research.

While Monsanto’s 2014 net sales of vegetable seeds, at $867 million, were a fraction of what it sold in seeds and traits for corn ($6.4 billion) and soybeans ($2.1 billion), according to the company’s SEC filing, Monsanto is building a robust division nonetheless. In 2014, it included 21 vegetable crops sold in more than 150 countries, allowing the company to slowly inch its way out of the center of the grocery store and into the world’s ever busier outer aisles.

Nor is this just about capturing the most lucrative and discerning broccoli-eaters: The company is setting its sight on global vegetable domination. “A big part of our focus is expanding the geographic scope of production in order to achieve a global market,” Robb Fraley, Monsanto’s executive vice president and chief technology officer, told Quartz. It’s testing several different seeds to make sure Beneforté can grow year-round, in different regions depending on the season, to make for a consistent product that is available everywhere, all the time. It doesn’t want Beneforté to be the Champagne of broccoli; it wants it to be the Coca-Cola of broccoli. If anyone can achieve that with a vegetable, it’s Monsanto.

More broccoli-y than your average broccoli

Beneforté broccoli and Monsanto’s other vegetables, like the non-tear-inducing EverMild onion, the smaller BellaFina bell pepper, and the sweeter Melorange melon, are not genetically modified organisms (GMOs). They are the results of selective breeding, the age-old process by which farmers make better crops by crossing varieties with desirable traits (though as Ben Paynter explained in Wired, Monsanto’s computer programs have both sped up and replaced much of the dirty work). Seminis’s technology allowed it to capitalize on the nutrition research by Beneforté’s original developers, breeding commercial broccoli varieties that had high levels of a beneficial compound.

Beneforté, a cross between Southern Italian wild broccoli and the conventional kind, has powers amply demonstrated in scientific studies, like its high levels of glucoraphanin, which your body turns into a cancer-fighting, potentially cholesterol-lowering compound called sulforaphane. A recent study (albeit partly funded by Seminis) found that people who ate Beneforté for 12 weeks had three times as big a drop in LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels as those who ate regular broccoli.

The taste is distinctive, too, though not everybody thinks it’s an improvement. When we fed it to Quartz staff, one said it was “what broccoli should taste like,” but another found it “way too broccoli-y.” And when put head-to-head in a blind taste test with Whole Foods’ organic California variety, it lost 5-3.

But while onions that don’t make you cry and less wasteful peppers solve actual, albeit minor, problems, few would argue that broccoli isn’t healthy enough. So why try to make it better?

Because, a Monsanto spokesperson told Quartz, consumers are always looking for more nutrition. Monsanto improves soy and corn seeds by upping the crops’ quantity, but in vegetables the focus is on quality—and giving them recognizable brand names so consumers can tell the difference. Ultimately, the fact that Monsanto is improving an already essentially perfect food shows the company’s commitment to becoming a dominant force in vegetables.

The danger of broccoli domination

Yet there is reason to worry if Monsanto achieves its goals. By helping farmers multiply their yields of corn and soy—and restricting the kind of business they could do with its competitors—Monsanto turned itself into a grain superpower. Doing the same in vegetables will not only give the company even greater economic and political clout but could also limit genetic diversity and global food security.

Monsanto likes to downplay its size. “We sometimes get a lot more credit for being bigger than we are,” Fraley said, drawing comparisons to market dominators like Apple in technology or Coca-Cola and Pepsi in soft drinks. “We’re probably way less than 10% of the global seed market.” Other estimates say Monsanto’s share of that market is about one quarter or as much as one third (paywall).

Whatever the size of its share, though, Monsanto’s increasing influence in that market is undeniable. A 2009 investigation by the Associated Press said the “world’s biggest seed developer” was “squeezing competitors, controlling smaller seed companies and protecting its dominance over the multibillion-dollar market for genetically altered crops.” It found Monsanto’s patented genetics were in 95% of the US’s soybean crops and 80% of its corn. (Monsanto told Quartz that “competition is extremely robust in the seed industry” and that it “must work to earn a farmer’s business each and every year.”)

The company tamped down its anticompetitive practices once attorneys general in states like Iowa and Texas started investigating them in 2007 (with the US Department of Justice following their lead in 2009), as Lina Khan of the New America Foundation wrote for Salon in 2013. But, Khan told Quartz, “the damage is already done.” As its recent SEC filing explains, the framework for Monsanto’s sales is now set. Much as it did with commodity crops, the company says its plans for vegetables are to “continue to pursue strategic acquisitions in our seed businesses… expand our germplasm library, and strengthen our global breeding programs.” Thanks to the “multiple-channel sales approach” it has used for corn and soybeans, it says, it has a built-in advantage in this market.

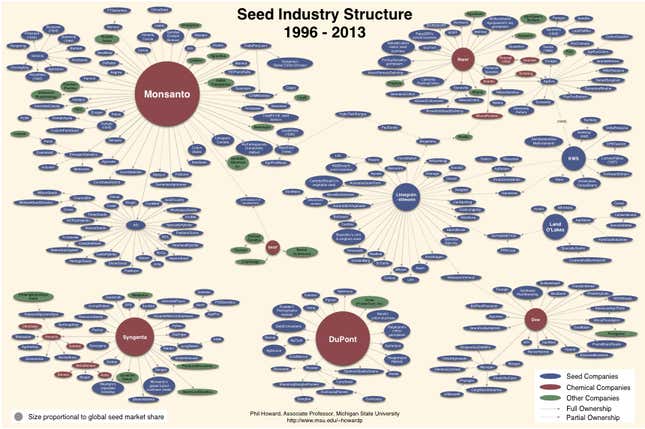

“This is an industry that used to be very competitive,” Philip Howard, who does research on the food industry at Michigan State University, told Quartz. “In the 70s there were thousands of seed companies,” he said, but now, as his chart on the Seed Industry Structure shows, a few large companies own nearly all of the small ones.

Control through IP

One way that Monsanto has exerted and benefited from its increasingly consolidated control is through intellectual property. When Monsanto patents a seed, the Associated Press showed, it gets a say in nearly everything a farmer wants to do with it. Monsanto contracts, for example, “effectively lock out competitors” from adding their own patented traits to any crops with Monsanto’s genes, which for corn and soy in the US, is nearly all of them.

“What gives me pause about [Beneforté] coming from Monsanto is their approach to intellectual property,” said Jim Myers, a professor of vegetable breeding and genetics at Oregon State University. “I’m an old-school breeder and what I see is that when people start using patents and business models like this to tie up the germplasm, it prevents the overall progress in a particular field.”

Fraley, unsurprisingly, disagrees with Myers’ assessment, arguing that Monsanto has actually helped progress. “We license our technology to well over 200 companies around the world,” Fraley said, referring to all of its technology, not just its vegetable seeds. “We have gone way out of our way to build a business based on open architecture and broad licensing.”

But Monsanto does patent its vegetables and their traits, as it does for its genetically-modified soy and corn. (Licensing for vegetable seed technologies is actually available through an online portal.) And the company confirmed that at least some of those restrictions will be enforced with vegetables like Beneforté. “The Beneforté broccoli seed that growers plant is a special hybrid seed,” a Monsanto spokesperson told Quartz over email. “It is not standard practice for commercial vegetable farmers to save and replant seeds, especially not with hybrid seed.”

Why genetic diversity matters

“Most of the food for mankind comes from a small number of crops and the total number is decreasing steadily,” agronomist Jack Harlan wrote in his book Crops and Man in 1975. “More and more people will be fed by fewer and fewer crops.”

Forty years later, a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences quoted those lines and agreed: ”The rate of movement toward homogeneity in food supply compositions globally continues with no indication of slowing.”

This increasing homogeneity is often traced back to the Green Revolution, a period between the 1940s and 1960s when high-yielding varieties of grains—and other advents of modern agriculture like synthetic fertilizers and modern irrigation systems—completely changed the way food was grown. While it is often credited with saving a billion people from starvation, the Green Revolution also preceded a fall in diversity in crop production. (Other causes, like an increasingly globalized food system, are also thought to have contributed.)

In 1991, the New York Times warned (paywall) that “the diverse varieties of traditional crops and wild plants they need to breed more productive new strains are in jeopardy.” By 2000, when the loss of genetic diversity was considered a given, the UN said the main reason for it was “the replacement of local varieties by improved or exotic varieties and species.” In 2005, the US Department of Agriculture published a report attributing the decline to several factors, including “the dominance of scientifically bred [crops] over farmer-developed varieties.”

If Monsanto repeats the domination it has achieved in corn and soy with broccoli and other vegetables, restrictions on breeding and a loss of genetic diversity seem inevitable, even with Monsanto funding seed libraries and licensing its genetics. This might not sound like a major problem, but it could be one day.

“Everybody in the country growing the same variety of broccoli because it’s the hot new thing may not be a good long-term plan,” said Patty Lovera, assistant director of Food and Water Watch, a non-profit organization that advocates for healthy food and clean water. Different varieties, she said, “might come in handy if the climate changes.” A 2010 UN report agrees with that assessment, as do other experts. “Less diversity in seeds makes us more vulnerable to drought and pests and any number of factors,” said Howard. Or, as Tony Sarsam, CEO of Ready Pac Produce, described agriculture: “God is very active in our business.”

This is not theoretical. A lack of genetic diversity in Irish potatoes in the 1800s, for example, likely exacerbated the potato famine that killed an estimated one in eight Irish. More recently, the widespread corn blight in the US in 1970, estimated to have reduced yields by 20%-25% across the country, is largely attributed to the fact that approximately 85%-90% of the corn grown in the US at that time had a gene that made the corn easier to breed, but also—unbeknownst to farmers—made it susceptible to a fungus that until then had been considered a minor disease.

Even without an act of God, diversity is important for the food industry. Bulk buyers rely on it to find the best varieties, depending on their needs. While one might be looking for the best apples for cutting, another might be looking for the longest lasting, while yet another wants the apple that is the sweetest. Reducing the available varieties of a kind of produce will necessarily limit how that produce can be sold.

Monsanto doesn’t appear to be worried that Beneforté will cause the variety of broccoli seeds to dwindle. Its plant breeders “breed in natural resistance to certain pests and/or diseases” and the company “sells dozens of different broccoli products to meet the needs of different growing regions and consumer preferences around the world,” a Monsanto spokesperson said. “We are also one of many other vegetable seed companies that develop broccoli seeds. Farmers have many choices when it comes to the broccoli seeds they purchase and plant.” The spokesperson also pointed to Monsanto’s investment in gene banks, including one in Woodland, California that preserve “rare and extensive collection of vegetable seeds from around the world.”

Most consumers, though, probably aren’t choosing their vegetables based on potential corporate monopolies or their impact on genetic diversity. They’re looking for something healthy, tasty and easy to cook. Beneforté, with its extra cholesterol benefits, strong broccoli flavor and ready-to-use florets, is trying to be just that. And with Monsanto behind it, how can it not succeed?