How do you prove you’re not dead to someone right in front of you? It shouldn’t be difficult, but in a recent case in China (link in Chinese) it was almost comically so for a 74-year-old woman trying to draw her pension at a local telecommunications bureau.

Not that she didn’t come well prepared with documents. The woman, in the coastal Fujian province in southern China, brought along her identity card and her hukou ben, the household registration book that identifies a person as a resident of an area in China’s civil registry system.

But the bureaucrats felt the need for some kind of paper-based proof that the woman standing in front of them was indeed alive, and not dead. What they needed, essentially, was a “life certificate.”

The woman turned to the local police for help.

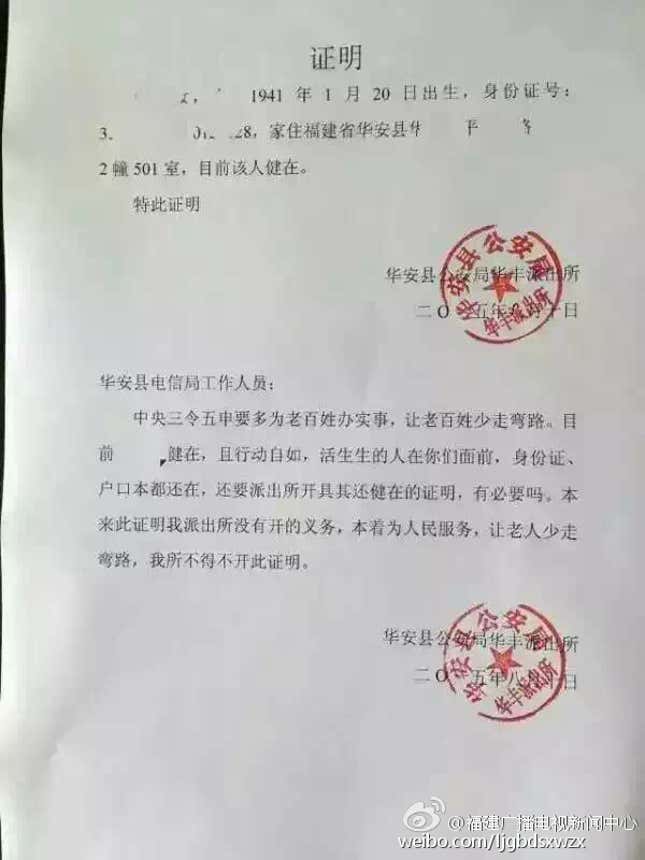

The police issued a statement of living for her—and added a statement of exasperation for themselves:

To the staff of Hua’an county telecom bureau:

The central government has given repeated orders on doing practical things for ordinary people, and avoiding detours for them. Right now XYZ [her name was covered] is still alive, and can walk easily—a living person is in front of you. She also has both her identity card and houkou ben. Why do you still need a proof from the local police station? Is that necessary? Originally, we have no responsibility to give this proof, but in order to serve the people, and to avoid detours for the old woman, we have no choice but to do so.

—Huafeng police station of Hua’an county public security bureau

Aug. 10, 2015

Such an incident is not uncommon in China, where a citizen needs to get 103 certificates (link in Chinese) from cradle to grave, as one legislator in Guangzhou counted.

Many citizens have been forced to make tedious efforts to obtain weird certificates from government departments in order to, for example, get paid or compensated, or to inherit or buy a property. Life, death, or “single” (as in not married) certificates are relatively normal ones. Others might ask you to prove that your relatives are your relatives—even if they’re your parents or children.

A Beijing resident surnamed Chen was reportedly (link in Chinese) asked by a travel agency to prove his mother was his mother, after he listed her as an emergency contact before traveling abroad in April. For that he had to visit the local police station holding his mother’s household registration—300 kilometers away in the Jiangxi province.

“How ridiculous! The citizen only intended to go traveling abroad and take a vacation,” said Chinese premier Li Keqiang, referring to Chen’s experience at a State Council meeting in May. Li has been seeking to simplify administrative procedures during his tenure.

Added Li: “I wonder whether these government departments are caring for the public, or intentionally obstructing them.”