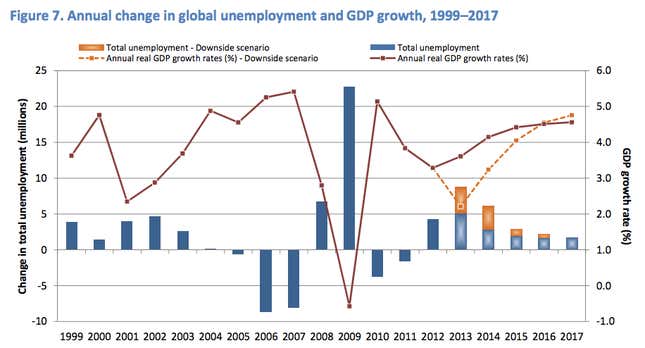

The theme of this year’s Davos gathering is “Resilient Dynamism,” and whatever that means, it probably doesn’t mean, “We’ve got a global unemployment crisis on our hands.” But the chief of the United Nations’s labor agency is urging the optimistic attendees to focus on one of the world’s worsening economic indicators: After decreasing in 2010 and 2011, unemployment jumped last year and will keep growing in 2013.

“We lost over 4 million jobs—4 million more unemployed in 2012,” International Labor Organization chief Guy Ryder said during a panel discussion at the World Economic Forum. “For 2013, it’s another 5 million, and it carries on. The horizon is not in sight.”

Those findings come from an ILO report released earlier in the week, showing that the global unemployment rate is at 5.9% and expected to rise to over 6% in the next two years. That’s above the recent peak of global employment in 2007, when the rate was at 5.4%, but still lower than the nearly 6.5% rate prevailing at the start of the century—which may be why there’s not that much overt concern about unemployment compared to, say, the European financial crisis.

But there are worrying trends underlying the figure, particularly the growth in unemployment among young people; 12.6% of them were unemployed, the worst level since 2000. While that is expected to improve in developed economies, the problem will get worse in emerging markets in eastern Europe, Asia and the Middle East. This kind of glut in youth joblessness can lead to diminished economic prospects in the future, not to mention social unrest, making this a political issues as well as an economic one.

Not enough is being done by governments, the ILO chief says, to spur growth in slowing economies—he mentions the 26% unemployment rate in Spain—or come up with public and private mechanics to improve the skills and job prospects of young people.

There’s some good news from the ILO: The middle class is growing in developing economies, lifting people out of poverty and creating a new source of demand for goods and services, even if that middle class is defined as living on more than $4 a day, $10 below the US poverty line. But then there’s bad news about the good news: Global wage growth is slowing, meaning fewer opportunities for people to enter that middle class.

Slow wage growth is caused in part by the less-than-competitive labor market: High unemployment means a worse bargaining position for workers. This plays out in global GDP, with a falling share of the world’s wealth going to labor and an increasing amount winding up in capital, particularly to cash-heavy corporate lockboxes.

Some of that money is funding the Davos experience, of course, where the general sense is that the last crisis is over and it’s far too early to think about the next one.