Much of what biologists know about octopuses—or what they knew until recently—is captured beautifully in “Deep Intellect,” an essay by Sy Montgomery, published in Orion Magazine in 2011. Montgomery learned that not only are these aquatic invertebrates highly intelligent, but also surprisingly charismatic.

“A home, or den, which an octopus may occupy only a few days before switching to a new one, is a place where the shell-less octopus can safely hide: a hole in a rock, a discarded shell, or a cubbyhole in a sunken ship,” she wrote. And now, according to new research on the previously unknown Larger Pacific Striped Octopus, we know that they’re not always holed up alone.

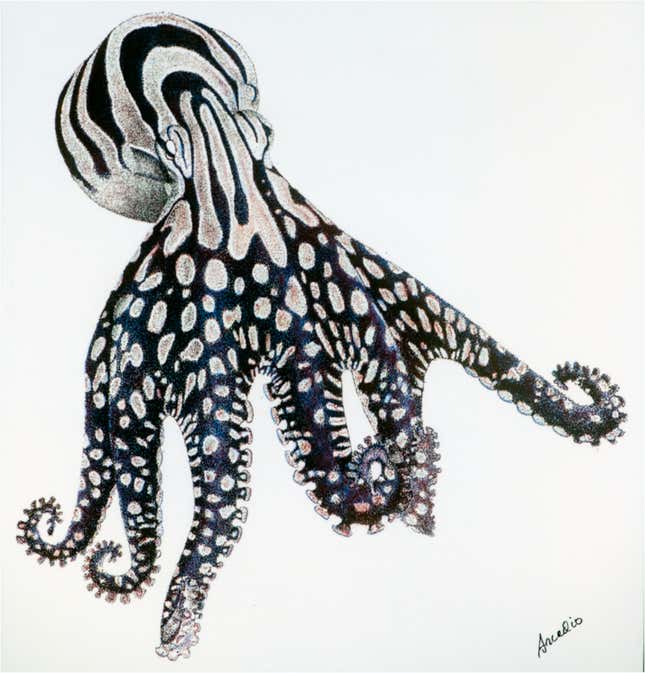

As the Associated Press reported yesterday, some California biologists recently began studying the new octopus, which lives off the coast of central America. And their research—based on two years of observations and just published in PLOS One—turns much of we knew about octopuses upside down.

Unlike other octopuses, Larger Pacific Striped Octopuses live relatively long lives, and mate—somewhat romantically—by shacking up together, for days at a time, in small underwater caves and discarded shells.

Most male octopi are justifiably afraid of being killed and eaten by their mates. But the Larger Pacific Striped Octopus engages in “beak to beak” mating behavior, with partners fully embracing each other. Males and females even share the housework: the scientists observed them cleaning food waste out of their living spaces. Interestingly, the female Larger Pacific Striped Octopus does not die after laying her eggs, like other octopuses do.

One caveat to this exciting discovery, according to the AP, is that these behaviors were observed in captivity and the octopuses may behave differently in the wild. But isn’t it nice, for now, to have an octopus that makes you feel all squishy inside?